In 2024 elections, digital crusades blurred the lines between official campaigns, authentic support and buzzer tactics

Yatun Sastramidjaja and Muhammad Alif Alauddin

The outcome of Indonesia’s presidential election on 14 February 2024 was no surprise. Even before the start of the campaign period, pollsters predicted a lead of around 40 per cent of the votes for Prabowo Subianto and his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka, which grew to over 50 per cent by February. Prabowo’s rivals remained far behind, at around 24 per cent for Anies Baswedan-Muhaimin Iskandar, and 17 per cent for Ganjar Pranowo-Mahfud MD. Yet, to supporters of each of the candidates, the campaign felt like a real thriller. This was especially so on social media, where supporters mixed with paid ‘buzzers’ – anonymous social media influencers – to hype-up their candidate. In doing so they created what Vidhyandika Djati Perkasa describes as a hyperreality around each candidate that seemed severed from any political reality.

As in the 2014 and 2019 elections, troops of buzzers were mobilised to influence public sentiments and boost the popularity of the candidate they worked for. But their strategies had shifted. Different from the polarising black campaigns and rampant disinformation seen in 2014 and 2019, buzzers used new tactics to seduce potential voters. This was partly in response to a more undecided electorate. Whereas in 2014 and 2019, voters were sharply divided between supporters of Joko Widodo (‘Jokowi’) and Prabowo, in 2024, with three candidates running, voters’ preferences were less determined. Moreover, Jokowi’s open support for Prabowo meant that the old propaganda narratives that pitched them as opposites needed to be revised. Following the lead of the official campaign teams favouring positive branding of their candidate, buzzers now focused on praising their candidate’s accomplishments, character and capacities. As a result, on social media, especially TikTok, the lines between official campaigns, buzzer operations and authentic support were blurred.

Television and Twitter

While buzzers and genuine supporters actively campaigned for their candidate throughout the campaign period, online activity was especially feverish around the five televised presidential and vice-presidential debates. Held between 12 December 2023 and 4 February 2024, from the very first debate, Anies Baswedan stood out as Prabowo’s fiercest challenger (although they were political allies in the past), while Ganjar Pranowo cautiously aligned with the position of Anies. This apparent Anies-vs-Prabowo battle offered all the drama that netizens love and that buzzers could easily exploit.

In the 2014 and 2019 presidential elections, Twitter (now X, but still commonly referred to as Twitter) was the key arena for shaping public opinion on the candidates. In 2024, netizens again flocked to Twitter to join the chatter during the debates. Hours ahead, they called on each other to ‘get the popcorn ready’ – that is, watch the debate and comment online – using hashtags like #DebatCapres2024 (‘2024 presidential candidate debate’) to keep the conversation together. During the live broadcast and hours after, an incessant stream of tweets was posted under these hashtags, often paired with hashtags that praised, criticised, or poked fun at one of the candidates. Some hashtags first appeared and went viral during the debate, either spontaneously, as a contagious response among netizens, or planned, as a scheduled buzzer operation.

For the experienced Twitter user, it was not difficult distinguish what was netizens’ chatter from that of the buzzer operations. Whereas netizens spontaneously commented on a detail of the debate including the candidates’ each word and gesture as it happened live on television, using the lingo of friend group chatter – such as, ‘Wow, guyzzzz, that punchline, he’s cooking!’ – a buzzer operation typically took the form of a sudden barrage of tweets with very similar messages and hashtags that had little to do with the debate.

For instance, after the first debate on 12 December 2023 – in which Prabowo performed poorly and seemed unprepared to counter criticism from his rivals, breaking out in a nervous dance (his campaign trademark) whenever he felt cornered – numerous tweets suddenly appeared stating ‘Our Prabowo, our choice’, paired with the hashtag #KitaMudaBeraniKeren, ‘we are young, daring and cool’, and the line ‘such fun with father Bowo and Gibran’ (SerunyaBareng AyahbowoGibran). In similar wording, each of these posts praised Prabowo as a true statesman who will work sincerely for the people’s welfare.

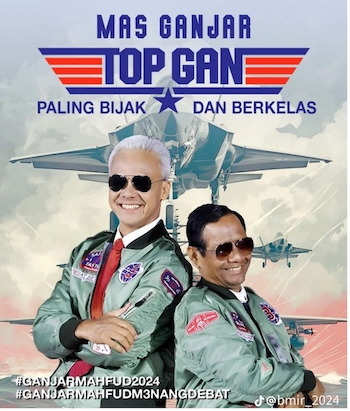

Buzzer operations also appeared in support of Ganjar-Mahfud. For instance, at the third debate on 7 January 2024, seconds after the pair appeared on stage donning matching outfits (doing so at each of the debates, a trademark of their campaign) – this time, wearing bomber jackets and pilot’s sunglasses, mimicking Hollywood actor Tom Cruise’s look in the action movie Top Gun – many tweets were posted with ready-made memes featuring the pair as ‘Top Gan’ (‘Gan’ for Ganjar). These posts, too, while made to appear as shared by genuine supporters, carried strikingly similar messages along the lines of Ganjar’s campaign slogan ‘sat-set’, meaning that they will get the job done fast. For Anies-Muhaimin such well-prepared buzzer operations on Twitter also occurred but were less common, as they appeared to receive genuine support on the platform.

Obvious buzzer posts received little engagement on Twitter; netizens ignored them or dryly remarked ‘here we go again with the buzzers’. The relative ineffectiveness of buzzers on Twitter in this election showed from a social network analysis of chatter during and right after the debates, conducted by Drone Emprit (a social media monitoring company). The analysis indicated that Prabowo garnered the largest volume of negative sentiments on Twitter, and Anies the largest volume of positive sentiments, reflecting their performance during the debates. During the debates for vice-presidential candidates, Gibran took the largest volume of negative sentiments. Going by netizen sentiments on Twitter alone, the Prabowo-Gibran pair seemed to be the least popular. This led many to believe that Anies stood a real chance of beating Prabowo, despite the polls telling otherwise.

However, different from the 2014 and 2019 elections, Twitter was no longer the main social media platform for digital campaigns. TikTok – which, according to pollster Indikator Politik Indonesia, had become the second most important source for political information for its 125 million users in Indonesia – had emerged as a key battleground to win over voters’ hearts and minds. Campaigners therefore avidly exploited this platform, primarily targeting swing-voters from younger generations. Buzzer messages that appeared to lack resonance on Twitter could thus be successfully amplified on TikTok, although using a different style and strategy, designed to appeal to young voters. This created parallel worlds on each of the social media platforms, where different rules of engagement and popularity apply.

The TikTok effect

As some Twitterers themselves remarked during each debate, the same views that were heavily supported on Twitter were often squarely opposed on TikTok. For instance, during the vice-presidential debate on 21 January 2024, where Gibran put on what was obviously a rehearsed act – pretending to search for a proper answer from Mahfud to one of his questions – reactions on Twitter and TikTok were worlds apart. On Twitter, netizens instantly criticised Gibran’s act, which they considered disrespectful towards Mahfud and, above all, ‘cringeworthy’. Many declared that they, as young people, did not feel represented by this ‘insolent brat’. Picking up on this sentiment, media reports and political analysts reiterated that Gibran’s ‘gimmick’ was a political blunder for crossing ethical boundaries.

Over on TikTok, as Twitterers were decrying Gibran’s ‘cringy’ act, videos went viral that remixed Gibran’s pose with different messages, positively framing him as a ‘cool and clever kid’ that dared to take on his elders. Some of the videos featured an AI-generated image of the pose in the cute ‘gemoy’ style of Prabowo-Gibran’s campaign, which became so popular on social media that Gibran eventually used it for his profile picture on his official accounts.

Likewise, Prabowo’s weak performance in the debates, whilst widely mocked on Twitter, received a remarkable spin on TikTok. Selected clips of Prabowo’s statements and gestures during each debate were edited of context and remixed into the typical fast-beat TikTok videos with a catchy sound, showcasing him as a true leader who is both funny and strong. Prabowo’s campaign team understood very well that the majority of ‘Gen Z’ voters did not bother to watch an entire television debate, but wanted to feel a sense of political participation in election times. Engaging with catchy Prabowo remixes on TikTok offered them a low-threshold opportunity for that.

So did dancing. Prabowo’s trademark dance move during the campaign triggered an online trend in the form of a TikTok challenge, where users are challenged to post videos of themselves mimicking viral TikTok content. Influencers were used to popularise Prabowo’s ‘joget gemoy’ or ‘cute dance’ on TikTok, and through clever use of TikTok’s algorithms, soon the impression was created that the entire country supported Prabowo by joining the ‘joget gemoy’ trend – from school children to office workers, in cities and villages. This type of virality made it difficult to discern which part of the trend was spontaneous and which was coordinated by Prabowo’s official campaign team or unofficial buzzers.

Besides the ‘Jokowi effect’ – or the popular president’s open support for his former rival Prabowo and eldest son Gibran, which also allowed for unfair interference and allocation of resources to the Prabowo-Gibran campaign – the ‘TikTok effect’ appears to be one of the key factors contributing to Prabowo-Gibran’s popularity and eventual overwhelming electoral victory. Different from Twitter – a platform popularly used by middle-class, educated Indonesians, who could easily discern buzzers – TikTok blurs the lines between the stage-managed and the spontaneous, as it is designed to stimulate organic participation. In Indonesia and other countries where elections were held in 2024, observers have called this the TikTok election year, recognising the impact of TikTok digital campaigning on election outcomes. In Indonesia, TikTok was not only instrumental for winning elections. It might also spark a democratic movement.

Abah mania, a movement

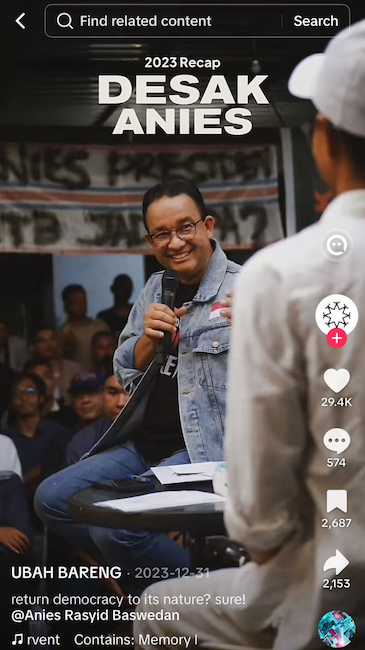

Running in parallel to the election campaign, TikTok also provided a platform for the emergence of a new youth movement congregated around Anies Baswedan. Whilst it was likely that some of the political parties in the Anies-Muhaimin camp employed buzzers to promote their candidate, Anies’ campaign also leveraged an army of ‘organic’ supporters. Besides Islamic groups, young people were at the heart of his support base. They were drawn to his powerful narrative of democratic change, social justice and real political participation, put into practice in his ‘Desak Anies’ (ask/urge Anies) campaign tour across the country, in which he held public meetings with citizens, mostly young people, inviting them to ask him anything they wanted and engage in open debate on issues they raised. His young supporters proudly called themselves ‘Anak Abah’ (‘father’s children’), a term of endearment likening them to Anies’ own children, and they fanatically promoted their ‘father’ on social media, especially TikTok.

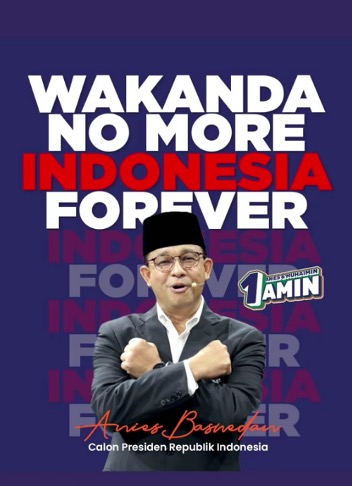

Anies’ official campaign team itself made good use of TikTok and other social media, featuring expertly edited recordings of Anies’ public meetings and offering generous peeks into his personal life, focused on the family’s food outings and cats. In response, Prabowo, too, began posing on social media with his cat. Anies was also the first candidate to use the interactive feature TikTok Live, resulting in funny clips that went viral of him getting confused at using this Gen Z platform, which augmented the spontaneity and artlessness around his persona. Mahfud then also tried his hand on TikTok Live, but the spontaneous character of this interactive feature evidently clashed with his stiffer persona. TikTok and other social media also effectively amplified Anies’ catchy campaign slogans, such as ‘Wakanda no more, Indonesia forever!’ The term Wakanda, referring to the kingdom in the Hollywood movie Black Panther, was often used by netizens as a substitute for Indonesia in critical posts about the government, to preclude censorship. The slogan thus cleverly captured netizens’ lingo and concerns to articulate Anies’ campaign program of democracy and freedom of speech.

But above all, the success of Anies’ digital campaign could be attributed to the Anak Abah, who created a fervent ‘Abah mania’ on TikTok and other social media, with its own viral trends. Different from the social media trends created around Prabowo-Gibran or Ganjar-Mahfud, the Anak Abah trend extended beyond the online realm, spurring young supporters to meet offline and launch grassroots initiatives for democratic change. And it extended beyond the elections. On election day, supporters flooded social media with the message ‘I vote for 1’, referring to Anies-Muhaimin’s ballot number. Once it became clear that their candidate had lost, they still took to social media with the slogan, ‘I am proud to be at the forefront of CHANGE’. Despite the loss, many vowed to join Anies in continuing the moral fight for a better Indonesia. For them, the movement transcended the immediate battle for political power, embodying a broader struggle for democracy rooted in ethical principles and social justice.

During the presidential campaign, Anies’ organic digital campaigners positioned him as not just a candidate but as a messenger of what governance grounded in transparency and accountability should embody. They fanatically amplified this message, transforming the campaign into a symbolic movement advocating for integrity, transparency and ethical governance – a rallying cry for voters disillusioned with the status quo. As such, Anies’ young supporters remained active after the February 2024 elections. They again launched a striking digital campaign during the regional head elections in November 2024 – in which Anies’ candidacy for the Jakarta gubernatorial election was blocked by the grand coalition of political parties supporting Prabowo – joining in on the ‘vote for all’ movement launched by the Urban Poor People’s Network, effectively rejecting the election as undemocratic.

Between seduction and inspiration

Due to Prabowo’s overwhelming electoral victory, which can be attributed to the ‘TikTok effect’ as much as to the ‘Jokowi effect’, the role of social media in elections has again been spotlighted as detrimental to the democratic process. Social media have indeed contributed to the rise of a personality-centred politics of ‘gimmicks’, from Prabowo’s rebranding as ‘gemoy’ (cute and cuddly) and Ganjar’s rehearsed move, to Ganjar-Mahfud’s matching outfits, to Anies’ slogan ‘Wakanda no more, Indonesia forever’. Coordinated buzzer operations have further degraded the quality of online political communications, but , this shows only one side of the ambivalent relationship between digital campaigning and politics. Social media offers a space for seduction, which make them a primary arena for political manipulation. Yet, they can also be a space for inspiration, spurring collective action on the basis of existing sentiments of disillusion as well as hope.

Yatun Sastramidjaja (Y.Sastramidjaja@uva.nl) is an Associate Professor of Anthropology at the University of Amsterdam. Muhammad Alif Alauddin holds an MSc in Development Studies from the International Institute of Social Studies, Erasmus University Rotterdam.