Sukarno's dedication to the arts and obsession with creating a nationalist ideal live on in luxury hotels he built in the 1960s

Originally known as the Ambarrukmo Palace or Kedhaton Ambarrukmo, the Ambarrukmo Hotel in Yogyakarta is one of four international standard hotels Sukarno ordered to be constructed in the 1960s. The others are Hotel Indonesia in Jakarta, The Bali Beach Inter-Continental in Sanur and the Samudra Beach Hotel in Pelabuhan Ratu. For Sukarno, building them was much more than a series of construction projects. It was a nationalist strategy focused on attracting international attention for the new nation. All four hotels house important examples of modern Indonesian art. Sukarno used art, architecture and monuments as revolutionary, ideological and diplomatic tools.

Sukarno was well suited for the task of symbolic nation building, both known as a nationalist, a revolutionary and an ideologue. He was also an art aficionado, collector and an accomplished amateur painter. As president he was also the most important patron of the arts and a trendsetter who did much to shape the development of a distinctive Indonesian modernist style. Sukarno was so fond of art that after his fall from power in 1966 he is said to have missed his collection and his association with artists more than anything else. He continued a centuries old Southeast Asian tradition in which art works and monuments are not only representations of cosmological orders but also serve to establish them as socio-political realities. Sukarno built on this tradition to construct what Robert Bellah called a ‘civil religion’ – a constellation of quasi-sacred rituals and symbols that binds a nation together. Sukarno’s Indonesian civil religion included romanticised, idealistic portraits of what Indonesia had been, was then, and the modern society it was becoming. The overarching theme was that of Indonesia as a modern, revolutionary, postcolonial society deeply rooted in the country’s traditional cultures.

The Royal Ambarrukmo Hotel combines Indonesian and Javanese political symbolism. It is situated on the grounds of the Kedhaton Ambarrukmo a royal residence constructed by Yogyakarta Sultan Hamengkubuwana (HB) VI in 1857. It is a miniature kraton (palace) that includes a pendopo, an open-air pavilion used as an audience hall (Gadri), a formal dining room (Ndalem Ageng), residential quarters, a Mushala or prayer room, and Bale Kambang, a meditation chamber. It was originally used as a politically neutral space for meetings with Dutch officials and foreign dignitaries and for meetings between the Yogyakarta and Surakarta branches of the Mataram royal family. Yogyakarta and Solo both claim to be the legitimate successor of the earlier Kartasura kingdom (1680-1755) and were on barely speaking terms since the mid eighteenth century. Meeting at either kraton presented significant protocol problems. Located on the edge of Yogyakarta on the road leading to Surakarta, Kedhaton Ambarrukmo was a (nearly) neutral space. After abdicating on 29 January 1921, HB VII lived there until his death on 30 December of that year. It was then used for various administrative purposes and gradually fell into disrepair.

A nationalist project

The Ambarrukmo hotel project was a joint venture between Sukarno and Sultan HB IX. HB IX played a major role in the Indonesian revolution. He was as committed to Indonesian nationalism as Sukarno and equally as committed to preserving the Yogyakarta monarchy. Architecturally the main building is in mid-twentieth century modernist style. Post-independence Yogyakarta was still predominantly rural and urban architecture was stylistically traditional Javanese or Dutch colonial. The Ambarrukmo Palace was one the first distinctively modern Indonesian buildings. The traditional Javanese style buildings from the Kedhaton Ambarrukmo were restored and incorporated into the modern hotel construction.

Sukarno personally supervised the art installations. They include two mosaics, Kehidupan Masyarakat Jawa Tengah (Community Life in Central Java) and Kehidupan Masyarakat Yogyakarta (Community Life in Yogyakarta) and a panel of relief carvings Untung Rugi di Lereng Merapi (Profit and Loss on the Slopes of Merapi). All of them are collages combining modern Indonesian and traditional Javanese motifs. They are romanticised depictions of life as it was in Yogyakarta and Java more generally in the early 1960s, told from slightly different perspectives. Taken together, they stress the importance of Yogyakarta as centers of Javanese culture and Indonesian nationalism. They depict an imagined reality in which harmonious Javanese culture is contained within modern revolutionary Indonesia. This evokes the Javanese Islamic metaphysical distinctions between lahir (external) and batin (internal) and wadah (container) and isi (content). The unstated message is that Javanese culture is contained within and/or is the spiritual essence of Indonesian modernity. One would not know from looking at them that Indonesia was rife with political and religious conflict in the mid-1960s.

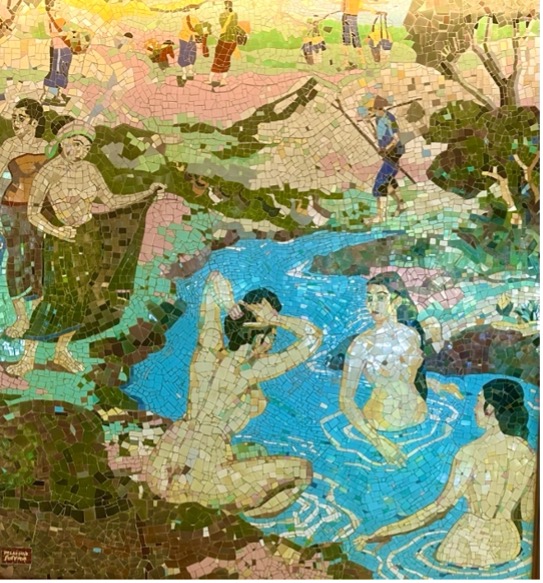

Kehidupan Masyarakat Jawa Tengah is the simplest of the three collages. It’s simplicity masks, and indeed conveys, ideological and symbolic complexity. Jawa Tengah is an ambiguous term. It refers to a cultural area that includes Yogyakarta and a province which does not. The cultural area is not precisely defined geographically. It is the area in which Javanese culture has been shaped by the court traditions of the Mataram kingdom and its successors Yogyakarta and Surakarta. The province was constituted in 1946. It includes territories that were formerly parts of the Surakarta kingdom and regions along the northern coast that have a different variety of Javanese culture more closely aligned with Muslim scripturalism. Surakarta was absorbed into central Java because its then ruler, Susuhunan Pakubuwana XII, chose not to support the Indonesian revolution.

The mosaic is a romanticised portrait of rural Java. Aside from a small image of the 9th century Buddhist monument Borobudur, there are no identifiable places. The images are of healthy and happy young people, most of them women, engaged in the daily activities of village life, farming, preparing food, bullock carts and a village market. A scene of young women bathing in a river may reflect Sukarno’s interest in erotic imagery. The overall simplicity and lack of symbols of conflict and modernity evokes his Marhenist ideology that locates the essence of Indonesia in self-sufficient village communities. It also resonates with the nostalgia many Javanese have for the (alleged) simplicity and tranquility of village life.

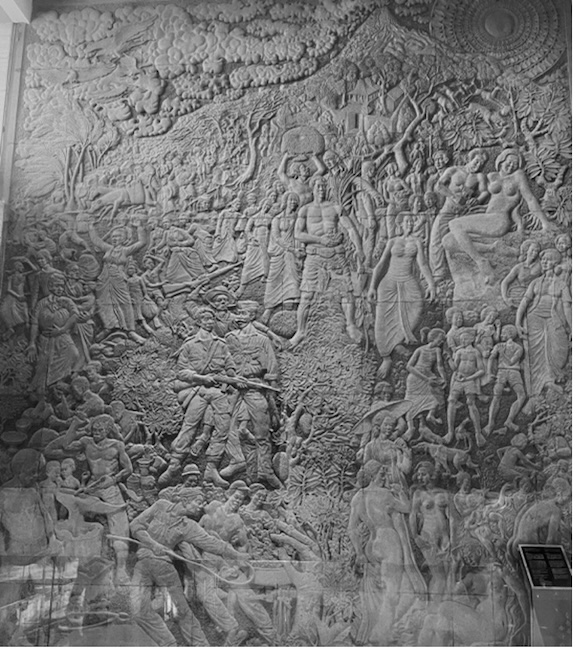

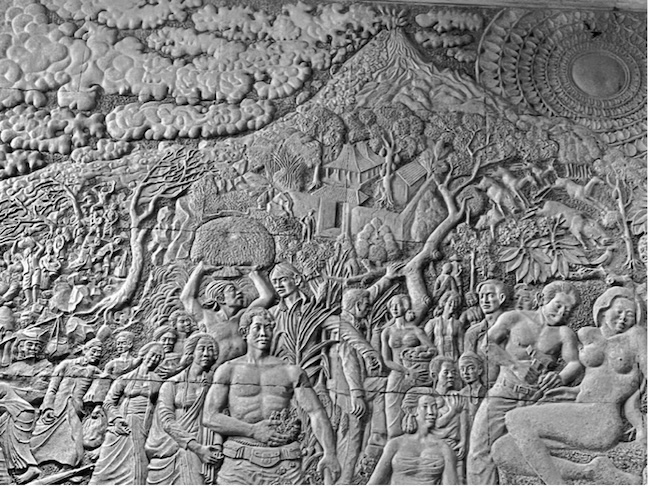

Kehidupan Masyarakat Yogyakarta and Untung Rugi di Lereng Merapi are each symbolically dense portraits of everyday life, Javanese culture and revolution in rural and urban Yogyakarta. Revolutionary struggle is a persistent theme, however, there are no overtly political symbols or anything that would point to the political parties that were contesting for power in the 1960s. Rather, there are idealised representation of the idea of revolution with images of strong men and women engaged in a courageous struggle against an unseen enemy.

Kehidupan Masyarakat Yogyakarta blends royalist, Islamic, Javanist images with those of urban life and revolutionary nationalism. Three images are particularly striking. The first features the five Pandawa brothers who are the heroes of wayang lakon (shadow plays) based on Islamicised versions of the Sanskrit Mahabharata epic. The largest image is Bima who is known for his strength, valor and quest for mystical knowledge. Sukarno was as fond of wayang as he was of art. He used wayang metaphors to describe the Indonesian revolution as a cosmic struggle between good and evil. He strongly identified with Bima. The second links the revolution with Diponegoro, the Yogyakarta prince who led a jihad known to history as the Java War against Dutch colonialists from 1825 until 1830. The third is a representation of Yogyakarta’s Islamicate civilization. It includes images of the Great Mosque and the Garebeg rituals that celebrate the three most important Muslim holy days, Id al-Fitr (Lebaran) at the end of Ramadan, Id al-Adha celebrating the Hajj (pilgrimage to Mecca) and Mawlid al-Nabi the commemorates the birth of the Prophet Muhammad.

It also includes images of every day life include horse carts (andong), and women selling traditional medicines (jamu) and making batik.

Untung Rugi di Lereng Merapi is stylistically very different from the two mosaics. It is a relief carving similar to those found on the ancient Buddhist and Hindu monuments Borobudur and Prambanan. It also includes elements of socialist realism, the Soviet art style that combined realist technique and idealist representations of life under socialism, or in Sukarno’s case Marhenism. Merapi is the volcano located to the north of Yogyakarta. Villagers living on its slopes are threatened by periodic eruptions the most recent of which was in 2010. Until the 1980s with the proliferation of cars and motorcycles and the resulting air pollution it was clearly visible nearly every day from any place in the city. It also figures prominently in the sacred geography of the Yogyakarta Sultanate. Sunan Merapi is the guardian of the mountain and is believed to prevent lava and pyroclastic flows from reaching the city. It is also the northern terminus of a mystical axis that extends through the kraton and ends at a shrine dedicated to Gusti Kangjeng Ratu Kidul, the Queen of the spirits of the Southern Ocean and spirit wife of the Sultans of Yogyakarta at Parangkusumo on the southern coast.

Thematically Untung Rugi di Lereng Merapi resembles Kehidupan Masyarakat Jawa Tengah in that it includes Marhenist images of village life. It also includes images of people fleeing from an eruption, revolutionary soldiers and Marhenist workers.

Untung Rugi di Lereng Merapi is the only one of the three collages that includes a dedication: ‘Presented to: Bung Karno the honorable artist, who provided us this gigantic field. A field for the national warrior artists to fight for honor’.

Mark Woodward (mataram@asu.edu) is a research professor at the Center for the Study of Religion and Conflict, Arizona State University. All images are courtesy of the author.