Sofyan Ansori, Aryo Danusiri, Paramita Utami

Baca versi Bahasa Indonesia

Following a seemingly fire-free period of more than three years, major fires yet again raged across the Indonesian archipelago in 2023, wiping out at least 1.16 million hectares of forest areas, mostly in Kalimantan and Sumatra. While considered ‘milder’ than previous fire disasters in 2019 and 2015, the 2023 conflagration still caused massive health, economic, and ecological impacts to people in Indonesia and also neighbouring countries. In Indonesian society these recent devastating fires also reignited a debate that accords disproportionate blame on Indigenous Peoples and their traditional agricultural practices.

The 2023 fires were not unexpected. Climate experts had predicted that 2023 would be another El Niño year with low rainfall and higher temperatures laying the ground for a high risk of fires, as it had in 2015 and 2019. Over the past decade, these previous tragedies had prompted regional and national governments to issue a stream of policies including multiple emissions reductions pledges, development intervention promises, and forceful fire suppression. The 2023 fires exposed gaps and failures in these policies and systems and raised critical questions: Why do fires keep happening despite all the restoration projects and prevention efforts? While this has long been part of global and regional climate conversations, how do fires actually mitigated at the local level? And, considering all the impacts, what do the 2023 fires tell us about Indonesia’s fire governance program and the role of Indigenous Peoples within it?

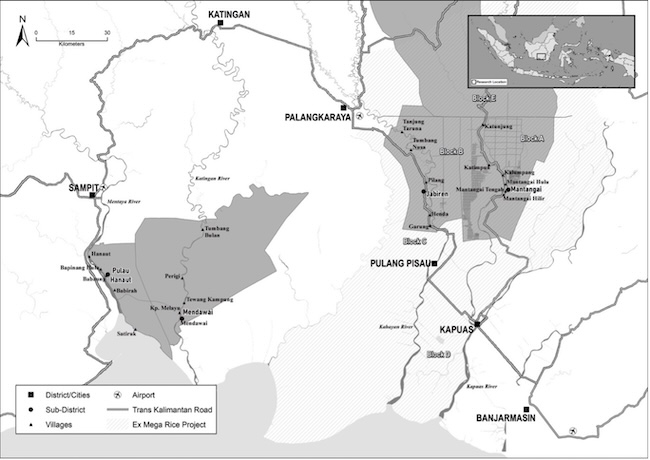

Responding to such questions, this edition foregrounds an interdisciplinary approach that focuses on fires as encounters between government and publics, policy and practice, commerce and indigeneity, nature and mankind (non-humans and humans). There is a friction between these multiple interlocking interests and everyday realities, that come together at the fire front. At the heart of this are the Indigenous Peoples of the fire prone regions. The articles we offer in this edition are informed by a research project, ‘Fire Play: Understanding and Documenting Indigenous Fire Governance in Indonesia,’ we carried out throughout the course of the second half of 2023 together with the Dayak peoples in four sub-districts in Central Kalimantan: Jabiren, Mantangai, Mendawai, and Pulau Hanaut.

Into the fire

Following disastrous fires in 2015, the Indonesian state established restoration and fire mitigation projects that primarily focused on Indigenous Peoples and their fire practices. As such, Indigenous Peoples, like the Dayak people in Central Kalimantan, are now performing crucial roles in community-based fire brigades at the village level. Among others these include, Masyarakat Peduli Api (Fire-Care Community), Regu Serbu Api (Fire-Attack group), and Regu Pemadam Kebakaran (Fire Suppressing Group). Involvement is voluntary, but expected, with some small payment from associated government agencies and corporations who engage the groups, however, compensation and the provision of training is limited.

The Fire Play research project sought to deepen our understanding of indigenous experiences in fire mitigation and management in Central Kalimantan. In selecting field sites for the study, we considered the history of fire-prone landscapes, the longevity of indigenous fire practices, the extent of this area as a priority for fire mitigation, and existing relationships between research team members and Dayak people in the area. Within these firescapes, the research focused on five concentric activities, including: observing village discussions, interviewing villagers on their fire knowledge, and following community-based fire patrols; documenting socio-cultural changes influenced by fire-related programs; conducting socio-economic surveys to put fire and climate initiatives into contexts; tracing anti-fire regulation and policy across levels of government; and analysing media and cultural representations of fires to connect the reality of fires from village to national level.

The project incorporates approaches and methodologies from anthropology, political science, and media and cultural studies to understand and document indigenous fire governance. Through our close engagement with the everyday reality of fire experience in this region, we argue that Indigenous Peoples are not mere ‘beneficiaries’ of climate initiatives but active subjects whose lives and cultural integrity matter amid the continuous efforts to cease environmental decline. By highlighting the struggle and pivotal roles of the Dayak people, we hope to initiate meaningful conversations against often malicious portrayals of Indigenous Peoples as fire starters, arsonists, or ecological criminals. Policy decisions and rulings predicated on saving the environment should not be pursued without consideration of the impacts on vulnerable groups.

The empty ‘prevention’

In accordance with the annual fire calendar we carried out our fieldwork from August to November 2023. As contributions to this edition show, our research teams experienced the flaming forests first-hand, encountering fires together with the Dayak people who welcomed our work. Considering the spread of the fires throughout the province, these 2023 fires might be considered to be more intense compared to those in 2019. They were not, however, even remotely close to the scale of the devastating 2015 fires, one of the worst seasons ever experienced in Central Kalimantan and Indonesia as a whole. The environmental as well as political and economic impacts of fires that year, inspired responses from government in the form of anti-fire policies, resources mobilisation, and the creation of Badan Restorasi Gambut (dan Mangrove, BRGM)—a non-structural agency under presidential directive—to complete what was described as a shift from a curative to a preventive approach.

Our findings show that the prevention approach is mere empty jargon. Indonesian leadership, from the president down to street-level bureaucrats, endlessly repeat a ‘prevention’ mantra with regards to fire mitigation. The big fires in 2023 seemingly nullified the promise of such a prevention process. Our research shows that what occurs on the ground in these fire-prone regions is in clear contradiction of such anticipatory ideas.

The reality is that state-led firefighting actions are not activated at the regency level until a prescribed number of fires are reported. When this threshold is reached it is only then that the governor is able to declare an ‘emergency’ status. This approach—of waiting until the fires are at significant levels—is counterintuitive to the true meaning of prevention. In late 2023 our fieldwork teams witnessed the very real impacts of these inconsistencies and contradictions. The timing of key prevention measures outsourced to community fire brigades, such as maintenance of canal blocks and deep wells, demonstrated a clear lack of planning and oversight. Some groups of Masyarakat Peduli Api were still carrying out processes of cleaning and checking the deep wells - the infrastructure to supply water sources - as fires already blazed across the province. Quite literally in the heat of the battle, members were torn between employing their resources to put out fires or follow the orders from BRGM to complete the maintenance tasks.

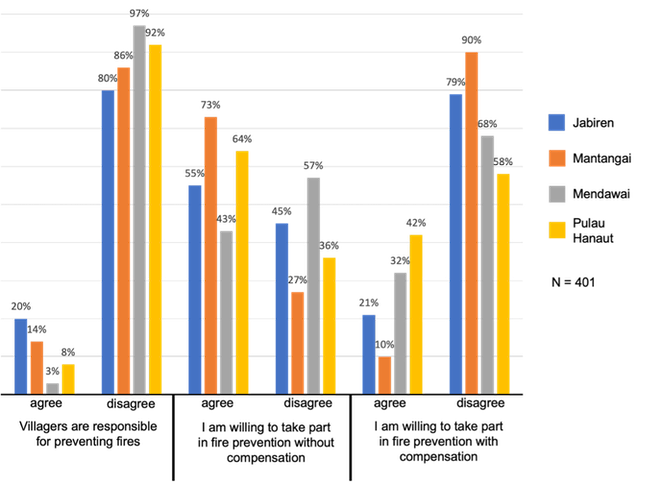

The failure of this prevention scheme perpetuates injustices to Indigenous Dayak people who make up the majority of the fire teams. The decentralisation of fire governance has drawn on this community to take on frontline roles in fire management and firefighting, where they are exposed to poisonous haze and intense heat. For their participation in these groups governmental agencies and also corporations that need help to supress fire from their concessions, pay the ‘volunteers’ Rp 100,000-150,000 (AU$10-15) per day. As our surveys found (Graph 1), despite these risks, overwhelmingly, the Dayak are willing to accept responsibility for preventing the fires and do all they can to assist. A severe lack of job opportunities and declining livelihood options, means people salvage whatever chance is offered to them. Such economic benefits are nothing compared to the devastation these fires bring to their lands and culture.

Illuminate!

We collectively witnessed the efforts of the Dayak people of Central Kalimantan as they struggled to negotiate between the politics of fire mitigation and management and the scorching flames around them. But away from these communities these experiences are little known or understood. The challenge is to offer a closer look at these tensions and to shed light on these everyday fire encounters to grasp the complexity of fire governance in Indonesia. As such, apart from publishing our findings in more traditional academic outlets, we are preparing multi-modal initiatives to communicate our efforts to the public, not only logically but also affectively. The team is producing a short documentary film, an ethnographic novel, and a short animation film in an effort to delve into and reveal our interlocutors’ everyday lives.

This edition is an inherent part of the public-oriented communication we are trying to pursue. The contributors draw attention to the top-down decision-making on fire governance that directly impacts these provinces and largely fails to consider the complex tensions within daily life, as Indigenous Peoples negotiate between the need to preserve their environment and to ensure that they can continue to make a living on and from it. They also highlight the innovative and considered ways in which communities are negotiating these challenges and, ultimately, striving to tell their own stories.

In his article Muhammad Soufi Cahaya Gemilang presents us with the big picture view of the ‘problems’ caused by forest fires in a warming planet. He posits that the global ideas and state-led visions of net zero emissions through a voluntary carbon market, do not necessarily fit with the fire realities on the ground in Indonesia. Hafiz A. Ramadhan examines how Dayak have responded to the government's efforts to instil environmental awareness through the use of coercive measures such as issuing legal threats displayed on banners across the regions, an enhanced police presence, and the spectacle of arrest. In his photo essay Michael Don Lopulalan focuses in on the ways Dayak communities reimagine their commitment to nurturing palm oil, a commodity that is key to their livelihoods, as part of their fire-defence mechanism. Observing male-dominated fire encounters, Hanina Naura Fadhila and Sofyan Ansori question the heteronormative logic of fire governance and community participation; and Edwin Jurriens, Aryo Danusiri, and Rugun Sirait highlight the efforts of young media producers in Central Kalimantan to present sensory fire experiences to geographically and emotionally faraway audiences.

Through this initiative, we directly address the contemporary challenges of communicating climate science, including the climate injustices experienced by vulnerable communities. The contributions to this edition, and the larger study more broadly, aim to inform existing climate policies in Indonesia as well as any new initiatives related to fire prevention and planetary crisis mitigation.

The Fire Play research project aims to nurture relevant research on Environment and Climate Change. The three principal investigators, Sofyan Ansori, Aryo Danusiri, Paramita Utami, from the Center for Anthropological Studies, Universitas Indonesia lead the project in collaboration with Jemma Purdey and Edwin Jurriëns from Asia Institute, Melbourne University and Angela Iban from Badan Riset dan Inovasi Nasional. The team harnesses the experience and expertise of Yayasan Puter Indonesia to organise daily operations in villages within four sub-districts in Central Kalimantan: Jabiren, Mantangai, Mendawai, and Pulau Hanaut. The project website is https://fireplay.fisip.ui.ac.id.