Truth and irrational violence in West Papua

Jenny Munro

Navigating false information is now an everyday experience in Indonesia and globally, but recent incidents in West Papua show how the rhetoric of the ‘hoax’ or ‘fake news’ may be used by those in power to justify violence, perpetuate discrimination, and deny people’s capacity to analyse their own social contexts.

On 23 February 2023, 12 people were killed in Wamena, a town in the central Papuan highlands. I have some personal experience of Wamena, which I first visited in 2006.

During my doctoral research I lived for a year with university students from Wamena in their dormitory in North Sulawesi, and later wrote about their experiences with racism in the education system. I travelled to Wamena with some students on their holiday break, and I was very drawn to the place, for many reasons, including its unique beauty in a gorgeous valley, how welcoming local people were, and the joy I saw as young people reunited with their relatives. There were clearly many hardships to life in Wamena, but I also saw fun and humour, rich histories, and deep cultural pride.

Over the years I have spent about seven months living with Indigenous families in Wamena, and I was there in 2012 when a battalion went on a rampage after a fight between some Indigenous and non-Indigenous men. Like everyone else in town, I fled to a nearby village where there were no military or police posts.

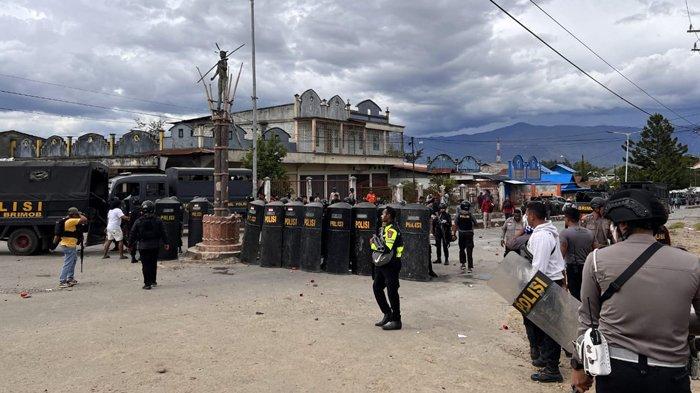

During this latest incident of violence, ten Indigenous Papuans were shot and killed by the police, and a further 18 were wounded. Two migrant men died of injuries caused by Papuan attackers. Media stories explained that some local Indigenous people had stopped a car near Sinakma market: the two non-Papuan (migrant) men inside were suspected of kidnapping a child. Police were called to the scene, where a crowd gathered. A confrontation broke out and police opened fire.

The day after the incident, Papua police spokesperson Ignatius Benny Ady Prabowo stated that ‘the riot was caused by fake news about the kidnapping of a child’. Angered by this hoax, he said, the crowd started rioting and attacking police, migrants, and migrant-owned properties. Similar statements were repeated in various media sources. Media stories over the subsequent days increasingly emphasised that the Indigenous ‘mass’ had been acting violently and ‘anarchically'.

The powerful First Commission of the People's Representative Council, which oversees national defence, foreign affairs, communication, information and intelligence, is pushing for an investigation into the alleged ‘hoax’ about child kidnapping, arguing that ‘intellectual actors’ who want to disturb the peace in Papua must be behind the hoax. The committee is also pushing for the security apparatus to seek out and prosecute those who spread the alleged ‘hoax’, and indeed for strengthened military presence in anticipation of the next ‘hoax’.

Thus, the blame for the incident has been fully displaced on to Papuans for ‘believing a hoax’ rather than the police who shot civilians. 13 people were initially detained and investigated for spreading false information.

A convenient narrative

This is not the first time the government has used an alleged ‘hoax’ to explain civilians being shot and killed by the police in Wamena. On 23 September 2019, violence led to the deaths of at least 33 people and the destruction of homes and businesses. Media reports quoted several officials, including President Widodo, who blamed the riots on rumours of verbal racial abuse by a migrant teacher toward a Papuan student. Jokowi insisted that the Papuan highlanders had been tricked by a hoax into attacking migrants and their businesses.

An extensive field investigation by the Jakarta Post later found convincing evidence that the unrest started after police shot and killed a Papuan man, Kelion Tabuni, who was part of a group that may have gathered for a planned protest against racism. They also found that almost half of the 33 people who died were Papuans shot by security forces.

'Tricked by a hoax' is a continuation of dominant racial ideas about Papuans – stereotypes that they are supposedly less intelligent than others, easily manipulated or duped, that they don’t understand technology so can’t spot false information, that they are hot-tempered and irrational.

The notion that Papuans are susceptible to external influences goes back decades, and is used as a convenient explanation for Papuan independence aspirations. In response to the latest violence in Wamena, Vice President Ma’ruf stated, ‘we are facing a Papuan population that is easily provoked, this must be addressed’. Specifically, ‘the apparatus has to anticipate this…so that armed criminal groups do not use hoax information as a tool to create chaos and scapegoats.’

The use of deadly force in this latest incident is not new, but the rationalisation of it has certainly evolved, tapping into global discourses about disinformation and the spread of conspiracies online.

The ‘tricked by a hoax’ narrative has been growing since 2019, when racist violence towards Papuan university students sparked nationwide demonstrations. In subsequent days and weeks, the government shut down internet connectivity in Papua on the grounds that social media and fake news online were causing unrest. Empowered by recent cyber security laws, the police were more concerned with who was sharing videos of racism than who was perpetrating racist violence.

It is clear that information wars have come to add a new layer of violence and complexity in West Papua, where history shows us that Papuans have good reasons to distrust the government and have repeatedly had their realities denied.

Little information has come out about the child kidnapping allegations at the centre of the recent violence (if indeed that was what led to the confrontation at all), but it is not irrational to believe that children are being exploited in Wamena. There are a considerable number of youth who are homeless, drug-affected, and vulnerable to violence. There is evidence of migrants and soldiers facilitating sex work by Indigenous girls.

‘Tricked by a hoax’ precludes the need for important questions about how to prevent violence and restore trust amid systemic racism and a history of manipulating the truth. It reminds me of something that Papuans students said to me repeatedly during my initial research – several said they felt that they, or their parents, had been ‘tricked’ by Indonesia into giving up their lands and being governed by others. A strong motivation behind their educational pursuits was to avoid ever being tricked again, and to restore their authority and systems.

Disinformation is damaging, but so is writing everything off as a ‘hoax’. The emphasis on social media disinformation continues a long tradition of punishing Papuans for questioning Indonesia’s truth, but ‘tricked by a hoax’ erases any possibility of debate or need for further inquiry – whatever brought people to Sinakma that day has been broadly dismissed and put into a black box, along with the need for questions about why Papuans are still being treated with irrational violence from the state.

Jenny Munro (jenny.munro@uq.edu.au) is an anthropologist at the University of Queensland.