Elite politics and Freeport Indonesia’s non-compliance continue to deny Timotius Kambu his owed wages

Elite politics and Freeport Indonesia’s non-compliance continue to deny Timotius Kambu his owed wages

Jeremy Mulholland and Abdul Fickar Hadjar

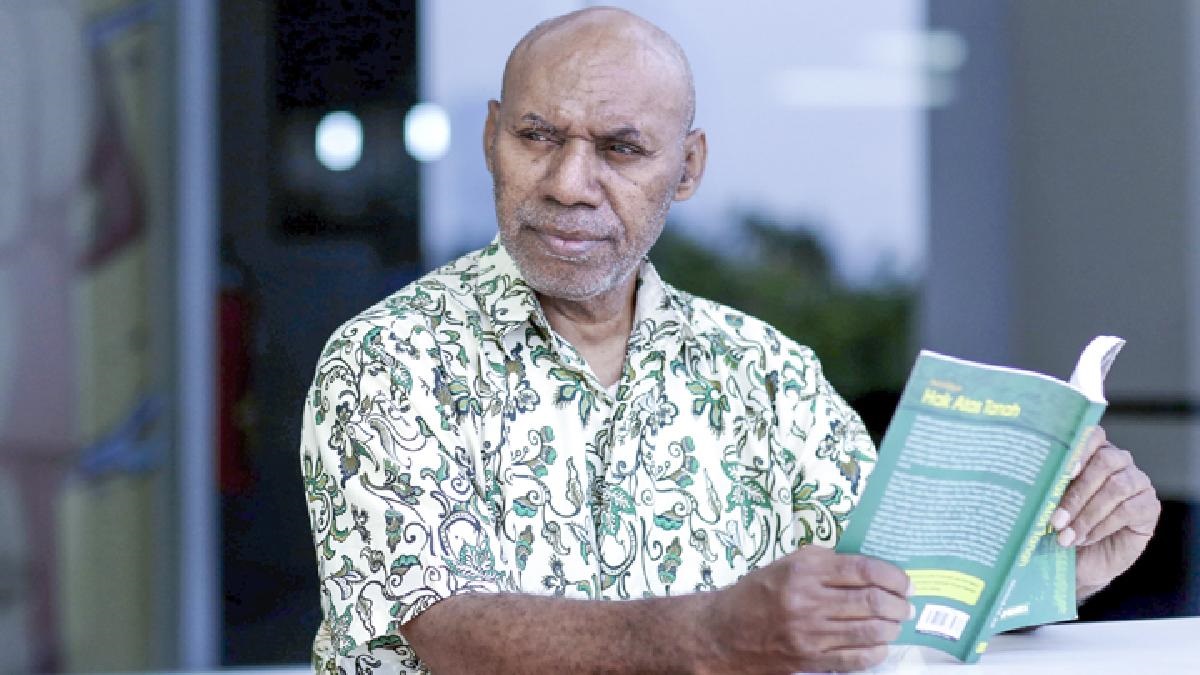

In Indonesia’s most protracted labour dispute in modern history, ethnic Papuan mechanical engineer Timotius Kambu, after suffering an unfair dismissal by Freeport Indonesia, has fought resolutely to reclaim his rights and dignity for almost 20 years. In 2001 Freeport fired Timotius on the pretext of a temporary employment contract even though he was a permanent worker at Freeport.

The David and Goliath dispute has passed through industrial relations and judicial processes, all the way up to the Supreme Court, but also included mediation by Indonesia’s National Parliament (DPR), Labour Ministry and Ombudsman. Without a lawyer and facing the legal division of one of the world’s largest mining companies, Timotius taught himself the intricacies of Indonesian law and achieved irrefutable legal success. A landmark ruling at Jayapura Industrial Relations Tribunal on 16 June 2005- which became final and binding on 19 August 2005 and reinforced by Supreme Court decisions 3/2006 and 33/2013- determined that Freeport Indonesia was guilty of the illegal dismissal of Timotius Kambu. As a result, by Indonesian law Freeport Indonesia had reached a legal ‘dead-end’ and since then has been obligated to pay all unpaid wages to and re-employ Timotius Kambu. Since then, however, Freeport Indonesia has defied those legal decisions and left a trail of non-compliance and obfuscation.

Meticulous fact-checking of Freeport Indonesia’s official statements has revealed that their Vice President of Corporate Communications Riza Pratama issued a set of misleading and irrelevant claims about the legal history of this case (Tempo, 26 June 2017 and 10 July 2017) (for elaboration see here). It is pertinent to ask why Freeport Indonesia chose not to simply pay Timotius, in alignment with their own Collective Labour Agreement, and later the various legal decisions, rather than going through years of litigation? The likely reason is that Freeport Indonesia does not want to appear susceptible to legal defeat and/or set a precedent. In the words of distinguished former Indonesian parliamentarian and Papuan community leader Ruben Gobay, ‘Freeport Indonesia leaders fear the Timotius case will open the flood gates and inspire other workers involved in labour disputes with Freeport Indonesia – such as Freeport labour union leader Sudiro – to follow in the footsteps of Timotius’s heroic struggle.’

A pattern of resistance

At the beginning of the Joko Widodo presidency in late 2014 and in 2015, Freeport’s non-compliance in the Timotius case culminated in Indonesia’s Ombudsman stepping in to closely monitor the case and the legality of the new Labour Minister’s actions. Based on a 27 July 2015 directive from Jayapura’s Industrial Relations Court, the Labour Minister Hanif Dhakiri and his staff were responsible for calculating the amount Freeport Indonesia should pay to settle the dispute. In the context of disagreements between the Ministry and Freeport over the method and scope of the calculation process, Freeport was forced to recalculate their financial obligations to Timotius for April 2001 to September 2015. The unintended consequence of this recalculation was that Freeport had at last officially acknowledged Timotius Kambu’s status as a permanent worker.

Although Freeport attempted to underestimate the size of their financial obligations without disclosing their calculation methods, the director general of labour development and supervision A Mudji Handaya stipulated that Freeport Indonesia owed Timotius Rp.12 billion (A$1.2 million), an amount never challenged by Freeport Indonesia in Jakarta’s State Administrative Court.

In this context, Freeport resisted making payments, attempting to subvert the implementation of mandated financial obligations. For example, in 2010, thanks to an informal alliance with Supreme Court Chief Justice Harifin Tumpa (2009-2012) whose combined authority over and expertise in civil law was used to manipulate the cassation process and compensation-based verdicts, Freeport won a controversial Supreme Court ruling (857, 2010), which nullified the 10 July 2007 Jayapura Industrial Relations Court order (or penetapan).

There are two ways of looking at the legal ramifications of that 2010 Supreme Court ruling. On the one hand, with the 2007 court order out of the way, Freeport had achieved its strategic objective of terminating the mandated auction of Freeport assets (seized by the Indonesian government), which should have yielded funds to pay Timotius’s wages. On the other hand, the 2013 Supreme Court Legal Opinion clearly stipulated that the 2010 ruling had not superseded or undermined the validity of the 2006 Supreme Court Reconsideration or the 2005 ruling from Jayapura Industrial Relations Tribunal.

Ironically, an unintended consequence of the 2010 Supreme Court ruling was that it enabled a resumption of the calculation process relating to Freeport’s financial obligations. Consequently, Freeport’s obligations – including unpaid wages, pension and family benefits – have blown out to at least Rp.240 billion and Freeport’s non-compliance has pushed the labour dispute into the criminal justice system.

Criminal charges

This David and Goliath struggle becomes even more imbalanced in the context of a 'corrupt politico-business environment'. Prior to 2016, in relation to Freeport Indonesia's non-compliance with the Jayapura’s Industrial Relations Tribunal verdict or Supreme Court rulings 3/2006 and 33/2013, Freeport Indonesia's leaders apparently experienced legal and political difficulties – but most of their cases were either terminated, or remain unresolved.

For example, Clementino Lamury (executive committee member) was the first decision-maker to be named a suspect in a defamation case reported at the South Jakarta Police Station. Strangely, he secured an ‘Order for Termination of Investigation’ signed by Jayapura’s deputy police commissioner Ridho Purba. Subsequently, Freeport Indonesia's president director at the time Rozik Boedioro Soetjipto (former Minister of Public Works) was named a suspect in an industrial-relations based criminal case at the National Police Headquarters. Without any termination of the investigation against him, Rozik's status continues to remain unchanged.

In general, legal problems faced by Freeport Indonesia's leadership team have suspiciously vanished. There was however one well-known scalp in this labour dispute. Freeport Indonesia's executive vice president Sinta Sirait was reprimanded officially by the Labour Minister Muhaimin Iskandar and forced to resign from her position at Freeport Indonesia on 1 March 2013.

In 2016 Timotius Kambu’s case against Freeport Indonesia made headway once again with the enactment of the Supreme Court’s Regulation on Case-Handling Procedures of Corporate Crimes (13/2016). The Corporate Crimes Regulation is intended to not only help facilitate investigations and prosecutions against corrupt companies but also bolsters legal certainty for workers who pursue companies engaged in wage theft and money laundering. As the Timotius case initially occurred before the establishment of Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) and was not associated with ‘state losses’ and ‘political corruption’, KPK leaders encouraged Timotius to file corruption allegations against Freeport Indonesia with the National Police.

On 25 January 2017 Timotius reported Freeport Indonesia's leadership, including its president director, to the National Police’s Criminal Investigation Division based in Jakarta. The criminal allegations are as follows: Freeport Indonesia’s leadership team is accused of committing a corporate crime in the form of wage misappropriation. The sudden resignation of Freeport Indonesia president director and former Indonesian Air Force Chief of Staff Chappy Hakim was probably the culmination of criminal cases initiated by Timotius Kambu and also parliamentarian Mukhtar Tompo.

In September 2017, police summonses of different members of Freeport Indonesia leadership team piled up. In addition to Chappy Hakim, Clayton Allen Wenas (alias Tony Wenas), Jonathan Rumainum, Clementino Lamury, Benny Johannes and Riza Pratama were all eventually investigated and interviewed by Jakarta’s Police by October-November 2017.

Although the police were ready in late 2017 for a preliminary hearing to let the case proceed and corruption suspects be named, to this day they have stopped short of this hearing. For two years there has largely been an absence of progress even though it is an extremely straightforward case and substantial legal evidence has been collected. With growing media exposure and academic scrutiny, Timotius Kambu’s formal complaint to Indonesia’s Ombudsman on 20 December 2018 resulted in the examination of the police’s handling of the case for potential maladministration. On 7 February 2019, the Ombudsman demanded that police immediately conduct a preliminary hearing – alas by April 2019 police inaction not only persists, but has deteriorated further with police investigators cutting-off all communication with Timotius Kambu and also proposing to transfer the case to Papua even though being acutely aware that the case’s location is Jakarta.

Golden eggs and entrenched bias

The big question is why has a criminal case of this stature focusing on Freeport Indonesia come to a complete standstill. Research by Indonesia’s National Police Academy (PTIK) and Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) found that corrupt practices are institutionally entrenched, especially at the apex of Indonesia’s elite politics and big business. In this labour dispute, potential criminal penalties relating to inaction on 2006 and 2013 Supreme Court rulings has given rise to opportunities for senior police to treat the case simply as a ‘goose that lays golden eggs’. Hidden biases in the law enforcement process behind this criminal case, and the warping of those processes, largely explain why justice has remained elusive for Timotius Kambu, as he seeks to claim what he’s owed by Freeport Indonesia.

This article is a revised version of an opinion piece published in Indonesian by Tempo magazine on 14 January 2019.

Postscript, January 2021

Since we last wrote in April 2019 about the illegal dismissal by Freeport Indonesia of one of their permanent staff, Papuan mechanical engineer Timotius Kambu, there have been several important developments in the case.

In early 2017 a police criminal investigation was initiated as a result of Timotius Kambu’s reporting of Freeport Indonesia’s non-compliance and mendacious claims refuting legally-binding rulings and financial obligations imposed on them by Indonesia’s Supreme Court and the Labour Ministry. Since then substantial legal evidence collected by the Indonesian Police in the criminal investigation into wage theft and money laundering resembles ‘an albatross around Freeport’s corporate neck.’ If rule of law applied, allegations that Timotius Kambu’s accrued wages were misappropriated by Freeport Indonesia would lead to full criminal investigation and prosecution.

On 19 August 2019, Indonesia’s Ombudsman found, however, that the Indonesian Police’s criminal investigation into Freeport was riddled by maladministration. The Ombudsman gave the Police a 30-day deadline to complete the case’s ‘preliminary hearing’ (gelar perkara) and naming of suspects. The Police, however, ignored the Ombudsman’s demands. Then a year later, the Police claimed they had held the preliminary hearing on the 23 July 2020 and, with sufficient evidence against Freeport, they would continue the case.

By January 2021, Indonesia’s Tempo Magazine revealed serious defects in regard to the police’s preliminary hearing.

First, the Police not only avoided using the standard terminology of ‘full criminal investigation’ (penyidikan) to describe the current stage of the case, but they also did not name any criminal suspects from Freeport’s leadership team, nor did the Police provide an update about the case to the Attorney General’s office, despite it being mandatory for them to do so.

Second, the Police flagrantly disregarded the fact that from the outset in 2017, Freeport’s Jakarta headquarters has been the locus of this criminal investigation.

Third, the Police also downplayed the value of Freeport’s alleged wage misappropriation which is greater than Rp. 12 miliar (AUD$1.2 million). Rather than a large case such as this being handled by the National Police, the case was put under the direct control of Jakarta’s metropolitan police. Based on the preliminary hearing, the Police have, however, arbitrarily decided to transfer the case over the regional police in remote Tembagapura in the highlands of West Papua.

On numerous occasions Tempo’s investigative journalists have tried to seek comment from the Head of the Jakarta Police’s Criminal Investigation Division, Tubagus Ade Hidayat, regarding his approval of these flawed decisions. As of mid-January 2021, Tubagus and other members of police leadership remain reluctant to discuss the case. This reluctance not only seems to reflect repeated attempts to conceal the defective handling of the case to date, but also invites deep concern of a plot being hatched by corrupt senior police, waiting for media scrutiny to subside, so they can terminate the criminal investigation, thereby exempting Freeport Indonesia from the criminal penalties that on the evidence so far deserve to be exacted. Time will tell...

Jeremy Mulholland (jeremypm@hotmail.com) is executive director of Investindo International and researcher in international marketing and Indonesian political economy at La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

Abdul Fickar Hadjar is criminal law expert from the Faculty of Law, Trisakti University, Jakarta.