A UNESCO-listed colonial mining town in West Sumatra raises complex questions about framing Indonesia’s industrial heritage

Katharine McGregor

According to local resident Om Nono Muma, most of residents in the small West Sumatran town of Sawahlunto are descendants from migrants who came from other parts of Indonesia, particularly Java, to work in the coal mines. The town was established following the discovery of significant coal deposits by the Dutch geologist, WH de Greve. Soaring global demand for coal created by the industrial revolution, led the Dutch government to open the first mine here in 1891 to fuel the colonial state’s ships and railways. The mine operated for over one hundred years, passing from Dutch to Indonesian ownership after the Indonesian revolution in 1949. In 1998 a drop in global prices and diminishing coal deposits saw the closure of the Ombilin Coal Mining Company. Some feared Sawahlunto would become a ghost town.

In 2001 Mayor Amran Nur drafted a new vision and mission statement for Sawahlunto focused on preserving and commodifiying the town’s mining heritage in order to make it a tourist destination. The local government restored colonial era buildings and created new museums. Eighteen years later, in 2019, UNESCO awarded Sawahlunto and surrounding areas world heritage status under the official name Ombilin Coal Mining Heritage of Sawahlunto. This includes the town of Sawahlunto and key sites connected to the history of mining and six museums. It also extends to the facilities and related infrastructure of the railway and the coal storage facilities at the Port of Emmahaven in Padang.

Through an analysis of key narratives in one museum connected to the renovated heritage, this article asks what a decolonial approach to the history of a coal mining town would look like? To what extent does this museum either challenge or reproduce colonial discourses in relation to industrialisation and resource and labour extraction?

Colonial heritage as technologically advanced

The Goedang Ransoem Museum (Rations Warehouse Museum) was opened in 2005. The site comprises several buildings that operated as the central kitchen from 1918 to 1942, feeding workers from the mine and local hospital. The process of creating the museum involved community consultation to find out more about the former kitchen, how it functioned and the whereabouts of many of the original instruments and equipment. This search led to the discovery of lost objects including the seven giant cooking pots that now stand in the centre of the museum.

The stories that came out of these focus groups, such as how miners’ hats were also used for collecting family rations, are featured in the museum. Given the common perception that museums are top-down institutions that tend to didactically present narratives, community involvement in this museum was novel.

The contents of the museum, however, reflect ongoing tensions within museum practice and in relation to UNESCO guidelines, around how colonial heritage is presented. In the last twenty years in Indonesia there has been extensive renovation of colonial heritage particularly colonial style buildings and ‘old towns’ of major cities such as Jakarta, Surabaya, Semarang and Malang with the view to commercialising these spaces to promote tourism. In this process there has been a tendency to place high value on colonial architecture and to celebrate Dutch era technological developments.

The Goedang Ransoem Museum fits this larger pattern, especially through its celebration of the use of modern technology. The coal fired steam furnaces that powered the kitchen are described in the museum panels and guidebook as ‘very modern at the time the kitchen was built’ and imported from the German company, Senking. A sentiment of awe at colonial advances is communicated through an emphasis on the unprecedented scale of the kitchen as ‘the largest’ in the Dutch colony of the East Indies. A museum brochure mentions ‘this impressive structure fed up to 7000 workers’. Through these narratives a colonial discourse of the Dutch bringing progress and modernity to Indonesia is replicated. The result is a largely positive evaluation of the impact of colonisation.

The emphasis on technological innovation and industrial machinery is in part also driven by Sawahlunto’s UNESCO ‘industrial’ world heritage status. One rationale provided on the UNSECO website for the listing of Sawahlunto is that its heritage demonstrated ‘the social and cultural interaction between the East and West and had resulted in transforming an isolated region into a dynamic and integrated series of cities.’ This narrative of the transformation of Sawahlunto correlates colonialism with bringing progress to remote places and replicates orientalist concepts of Eastern backwardness and Western modernity.

Glossed over in this framing is the environmental degradation of land and rivers where coal mining takes place and the link between coal and climate change. At a time when global efforts are underway to abandon coal, the celebration of industrial heritage connected with this mineral has a jarring dissonance.

Colonial labour exploitation

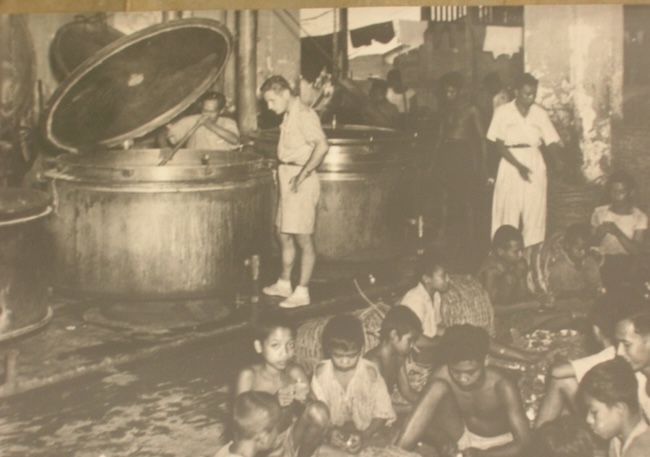

Despite the UNESCO requirement that new museums in Sawahlunto highlight industrial heritage, a more critical approach has been taken to colonial practices of labour exploitation. Across Goedang Ransoem Museum a series of colonial era photos are displayed. These photographs, often taken by colonial officials for the purposes of accentuating colonial progress, offer glimpses into colonial exploitation. A 1940 photograph of the mass kitchen, for example, shows young Indonesian children crouching in the forefront of the image eating.

A museum official explained that these were the children of mine workers who worked in the kitchen in return for a plate of food. What this suggests is that food provisions for workers’ families were minimal. The museum panels explain to visitors that worker rations comprised 1375 grams of rice, 125 grams of salty fish, 250 grams of vegetables and 125 grams of lepeh lepeh or traditional food, per day.

Perhaps the most confronting and damning critique of colonialism in the museum comes through discussion of the position of orang rantai or convicts. This expression refers to convict workers who were forced to work with their necks, hands and feet chained to prevent them from escaping. The museum displays plaques from the gravestones of these workers that show only a number for each deceased prisoner.

It is explained in the accompanying caption that ‘the numbers reflected the tattooed number marked on the body of each prisoner by the Dutch colonialists’. The caption emphasises the Dutch treatment of these people as ‘inhumane’, but also notes enduring stigmas towards them ‘because of the Dutch portrayal of these people as criminals or deviants’.

Local attitudes to convict workers have changed over time. The museum plaque also records that today some now consider them ‘heroes in the mining sector’ for helping to build the town. There is also consideration that these workers could have been imprisoned by the Dutch for a variety of reasons including political motives.

Decolonial subjects and decolonial approaches

The museum’s attention to the chained workers exposes a darker side of colonialism: the often invisible, and highly subaltern subjects: colonial labourers. Attention to these workers and the conditions under which they laboured to meet the demand for export products and build related infrastructure is not frequently profiled in colonial heritage sites.

The inclusion of stories of chained people in Sawahlunto heritage sites can be attributed to the pioneering research of Erwiza Erman (1999), whose social history of the mine first drew attention to these workers. Erman was also involved in the town’s heritage preservation. Narratives about these workers critically disrupt narratives of colonial industrial heritage as an unproblematised story of the arrival of progress and modernity in Indonesia.

In 2013, the town’s social history was also highlighted in a temporary exhibition called ‘Stories from Ombilin,’ which focused on oral history and intangible heritage such as unique cultural practices. The exhibition drew attention to how migration related to mine work led to the formation of a multiethnic community in Sawahlunto. The chained workers, for example, were of Javanese, Batak, Sundanese, Madurese, Chinese and Minangkabau backgrounds. This led to the development of a new shared language called bahasa tangsi, barracks language, so that workers could more easily communicate.

By drawing attention to these aspects of cultural formation the museum curators have taken a more community-centred approach to history that tells stories about local adaptation and resilience to colonial rule and displacement, rather than focusing the narrative on Dutch agency and change. This is another important decolonial aspect of the museum.

Overall, the Goedang Ransoem Museum suggests some interesting directions future museums in Indonesia might take to evaluate colonial history more critically, and bring to the forefront local perspectives and histories, rather than fall back on a tendency to narrate history from above. A decolonial approach to history also requires a critical evaluation of the celebration of industrial heritage and colonially introduced technology as equivalent to progress and development, especially in light of new awareness about the link between industrialisation and climate change.

Katharine McGregor (k.mcgregor@unimelb.edu.au) is a historian of modern Southeast Asia based at the University of Melbourne.