Indonesian martial arts comics do not flatter the rich

Gary Gartenberg

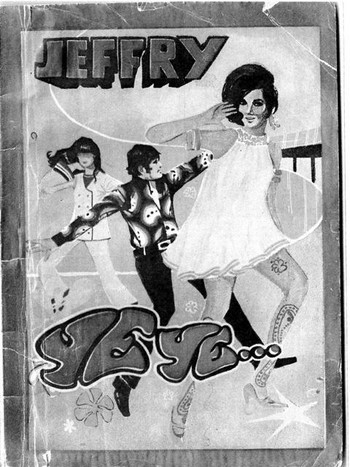

Tearjerker romances so generically cosmopolitan they could be set inany modern city in the world.The Cover of Yeye... Jeffrey, 1969. |

How do middle class and poorer Indonesians think about the rich? One answer can be found in an unlikely source: comic books. For decades these have been a popular medium of entertainment, particularly among urban working folk. They are a great reflection of popular attitudes toward the rich. In some societies, the wealthy are celebrated in comic books for their glamour, their ingenuity and their benevolence. While some Indonesian romantic comics are set in such a world too, this is not the case for the most popular genre of all: the silat, or martial art, comics.

The earliest Indonesian language comic books were created in the late Dutch colonial era, but domestic comic book culture really only came into its own after the revolution. The undisputed Godfather of Indonesian graphic storytelling is R.A. Kosasih. In the early 1950s President Sukarno himself urged Kosasih to create comic books with indigenous themes and values suitable for the new state. Most famous are his wayang comics that creatively retell episodes from the Hindu epics. These works still enjoy popularity today.

During the first two decades of the New Order regime comic book production expanded exponentially. New domestic genres emerged. These included the modern Cergam Roman Remaja, a teen female oriented genre of modern tragic romances, Cerita Silat Bergambar or Komik Silat, extremely popular martial arts fictions drawing on historical legends, as well as less successful attempts at modernist science fiction. Many hundreds of new titles within the silat (martial arts) and romance genres were widely distributed through private commercial lending libraries known in Indonesian as taman bacaan. Until electronic games began to displace them in the early 1980s, comic books were an important medium of entertainment.

Where is the money?

|

Pitung foils a rape, rescues a fair maiden, and cuts down the richChinese landlord, Babah BongPitung Matjan Betawi, A.S. Daniel, 1968. |

In Indonesian comics produced from the 1950s to the mid 1980s there appears to be no equivalent to the benevolent and extremely wealthy protagonists found in American comic books. Think of Bruce Wayne, the sophisticated tycoon who prowls the Gotham City nights as Batman, or Tony Stark, the corporate magnate and American defence contractor who fights villainy as Iron Man. Characters who amassed capital and lived in luxury were not idealised in Indonesian graphic fiction.

In Indonesian comics produced from the 1950s to the mid 1980s there appears to be no equivalent to the benevolent and extremely wealthy protagonists found in American comic books

Unlike America’s consumerist ‘new’ society, Indonesia of that period produced a qualitatively different set of signs reflecting a less overtly materialist attitude towards riches. Wealth was often measured in control over subjects, in sexual access to lovely females, in the possession of magical powers and in physical prowess. At the same time, material riches were attended with a sense of evil, impurity or corruption.

Legendary realms

The wayang comics and legendary tales of old Java produced by Kosasih in the 1950s and later by such comic book masters as Teguh Santosa and Jan Mintaraga were set in the opulence of royal worlds of the mythological or pre-colonial past. While wayang and legendary comics do illustrate a sense of prosperity in ancient kingdoms, such luxury serves more as a backdrop than as a point of thematic concern within the narrative. These classic comics are based on court tales of the pre-colonial past, and conformed to the propagandistic desires of ruling elites. Heroes of common origins are most rare in the palace tradition, as are intimate views of the lives of commoners. These ‘traditional’ comics thus in some sense revived feudal or royal values.

Teenage dreams

Like the classic stories, the modern romantic comics of the New Order era, written by such authors as Zaldy, Jeffrey or Jan Mintaraga, are set in pen and ink worlds defined visually by opulent features. This is a melodramatic popular literature of escape and erasure, oriented towards a predominantly young female audience with upward mobile aspirations. In these comics, money, fancy houses, expensive cars, electric musical instruments, discothèques, European fashions, and Western décors are constant elements of affluent settings for soap opera stories of passion, failed romance, and pathos. There is no sense of surrounding poverty, nor are there significant markers of locality such as traditional markets or wandering sellers of bakso or baskets of fruit. Traditional forms of dress are entirely absent. Instead readers are served up hermetic worlds of fabricated modernity divorced from the realities of Java in the late 1960s. These tearjerker romances are so starkly and generically cosmopolitan that with a few tweaks they could be set in any modern city in the world.

|

Pitung robs the rich and falls afoul of the Dutch colonial authoritiesChinese landlord, Babah Bong.Pitung Matjan Betawi, A.S. Daniel, 1968. |

It is in the genre of martial arts comics that the money and the behaviour of the rich are directly caricatured in an unvaryingly negative light. In a significant number of silat stories, money, materialism and the self-interested exercise of authority over others are linked to lust, greed, and tyrannical behaviour. Wealth and the rich are thus vilified, consigned to the ‘dark side’ and set in opposition to the pursuit of the virtues of the pendekar or noble warrior: knowledge, social responsibility, compassion, spiritual purity and potency.

Within the silat world the currency of true power is martial valour. Although rich villains can surround themselves with powerful, amoral mercenaries intent on steady employment and full rice bowls, the indomitable heroes of these tales rise to heights of supernatural martial attainment through myriad forms of asceticism, harsh discipline and a cultivated lack of pamrih or self-interest.

The political orders of the silat jungle can be likened to thugocracies, where might makes right, and the powerful are depicted as leeches upon the land and people of the archipelago. Pendekar are homespun heroes, simple men and women unencumbered by lofty ambitions or material trappings. Survival through skill in silat is thus an alternate construction of ultimate wealth in this narrative tradition.

The political orders of the silat jungle can be likened to thugocracies, where might makes right, and the powerful are depicted as leeches upon the land

The creation of the silat comic genre is commonly credited to the late Ganes TH. This famed and prolific author andartist created the iconic Si Buta Dari Gua Hantu (Blind One from the Ghost Cave) series, which began in 1967. Barda Mandrawata, the hero of this famous serial, intentionally blinds himself in order to attain the supersensory ilmu or magical science required to attain vengeance against the murderer of his family, Si Mata Malaikat (Angel Eyes). In subsequent tales he wanders the archipelago redressing evil wherever he finds it and aiding the weak and oppressed. The success of Ganes TH’s silat comics inspired a mass movement of comic book authorship that has yet to be eclipsed by any other domestic comic book genre.

Hard cases

Dutch colonial greed and wickedness are the subject of the short silat serial entitled Leonard Van Eisen by the highly regarded comic author Djair. A Dutch colonial administrator, mad with his own power, wantonly helps himself to the lands and property of the surrounding indigenous populace, until he falls afoul of Jaka Sembung, a Javanese ‘recidivist’ possessed of supernatural silat skills. Dutch physiognomy and attitudes regarding native land rights are sharply lampooned in this story of karmic consequence. The greedy and lascivious members of the Van Eisen clan meet horribly violent deaths at the hands of Javanese silat freedom fighters.

Si Pitung Macan Betawi (Pitung the Tiger of Batavia) by AS Daniel is a single volume comic that recounts the exploits of Pitung, the colonial era West Javanese silat fighter whose life-story later inspired the establishment of a museum in Jakarta. Such tales of Batavian silat fighters attained popularity through the prolific writings of the serial novelist Zaidin Wahab in the 1960s and ‘70s. In this Batavian Robin Hood story a silat adept uses his skills to torment the oppressor and aid the poor. A humble goatherd enjoying a close relationship with the kyai of a local pesantren, Pitung falls afoul of the colonial authorities and the local landowners when he resorts to banditry to sustain the downtrodden. At the climax, Pitung rescues a poor virgin who has been abducted and served up as a prospective ‘young wife’ to the evil and wealthy Chinese plantation owner Babah Bong. He foils the landowner's rape attempt and stabs him to death.

|

All those who strive to possess the gold, including Gitanjali, meet badends.Cover of Gitanjali, Teguh Santosa, 1976-78. |

As one final example, the late Teguh Santosa, known as the ‘King of Darkness’ because his comics are so sinister, was renowned for his artistic and storytelling skills. In Gitanjali he created a romantic tale of a doomed treasure hunt set in Java circa 1800. This adventure centres on the figure of Gitanjali, a gorgeous Javanese-born concubine from the court of Raja Ravi Shankar of Bihar in India who has fled the clutches of her lascivious master. She returns to Java to seek out an accursed treasure of looted Inca gold lost with a Portuguese ship that sank near Karimun Island off Java's north coast in the sixteenth century. Employing a map tattooed on her thigh, Gitanjali leads a rabble of competing warriors – Javanese, Indian and Dutch – on a race to the sunken gold. Devoured by sharks, stabbed and shot to death, or blown to smithereens, all those who strive to possess the gold, including Gitanjali, meet bad ends. Here the wages of avarice are, once again, early death.

The silat comic book fictions of the New Order provided a medium for euphemistic but critical social commentary. Being set in pre-revolutionary times helped them pass the scrutiny of military censors. Amongst the hundreds of titles published in those days are graphic novels beloved by generations of comic book enthusiasts, past and present. They are iconic achievements in the medium, deploying their own cultural grammar. The authors lampoon corruption, avarice, and lust in these pen and ink meritocracies of martial prowess. In the hardscrabble landscapes of these graphic novels, survival is the ultimate wealth.

Gary Nathan Gartenberg (8kumala8@gmail.com) is an independent scholar specialising in Malay/Indonesian language, literature and cultural studies with a particular interest in Nusantaran martial traditions. His PhD dissertation ‘Silat Tales: Narrative Representations Of Martial Culture In The Malay/ Indonesian Archipelago’ (University of California, Berkeley) was completed in 2000.

This article is part of The Rich in Indonesia feature edition.