Memo to SBY: solve your biggest human rights problem now!

Setyo Budi

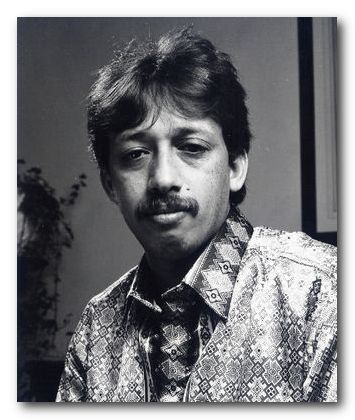

Munirhttp://www.salzburg.gv.at/rla2005pic_munir.jpg |

President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono won July’s election with a landslide. Amidst the general relief that Megawati and Jusuf Kalla lost – can you imagine Prabowo or Wiranto as vice-president? – one question continues to jar. Why does the brain behind Munir’s murder remain at large five years later? SBY’s failure on this issue hints at a darker side to his presidency. Good economic management is one thing, but maybe it is time to focus on human rights.

Munir Said Thalib was Indonesia's most famous human rights and anti-corruption activist between 1998 and 2004. He was Indonesia’s Anna Politkovskaya. An assassin poisoned him with arsenic on 7 September 2004, on a Garuda plane en route to Amsterdam. Utrecht University had invited him to pursue a master's degree in international law and human rights. He died in agony somewhere over Hungary, three hours before the flight landed at Schiphol airport.

In December the then newly-elected President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono appointed a fact-finding team to assist the police. He instructed all state agencies to collaborate with it. In March 2005 he said the murder investigation was a ‘test case for whether Indonesia has changed’, presumably a reference to the impunity that military officers had long enjoyed. In June 2005 the team reported to the president that it suspected the intelligence agency BIN of having been behind the assassination. The man suspected of administering the fatal dose was Pollycarpus Budihari Priyanto, a Garuda Airlines pilot and part-time BIN agent. Before and after, Pollycarpus made numerous mobile telephone calls to Major General Muchdi Purwoprandjono, deputy director at BIN.

In January 2008 the Central Jakarta court sentenced Pollycarpus to 20 years imprisonment (thus overturning an earlier acquittal that followed his appeal against a 14 year sentence). The same court sentenced former Garuda executive director Indra Setiawan to a year’s jail for facilitating Pollycarpus’ access to Munir on the flight. Muchdi was arrested in June 2008, but acquitted in December 2008, and the Supreme Court upheld the acquittal in June 2009. The court did not refer to the Muchdi-Pollycarpus conversations. Much remains unclear about the case. The Solidarity Action Committee for Munir (Kasum), of which Munir’s human rights organisation Kontras is a part, immediately protested that ‘the Supreme Court has abandoned justice principles… It has ignored the public interest’.

A much more worrying possibility is that SBY is simply too much part of the military establishment to pursue Munir’s murderers

Why has SBY been so weak on this? Professor Tim Lindsey, Director of the Asian Law Centre at the University of Melbourne, told me recently that Yudhoyono is constitutionally constrained by the separation between executive and judicial powers. But, he added, SBY has also failed to control BIN. ‘Like intelligence agencies in other countries, BIN is difficult to control. It needs to be regulated, reformed and brought into line with executive and legislative bodies,’ Lindsey said. BIN is a heavily militarised civilian institution. Its function is to co-ordinate all intelligence institutions and produce integrated intelligence for the president and parliament.

Military establishment

A much more worrying possibility is that SBY is simply too much part of the military establishment to pursue Munir’s murderers. The killing occurred two weeks before the second round of presidential elections, held on 20 September 2004. Usman Hamid, coordinator at Kontras, told me during his visit to Melbourne last June: ‘The information that [the fact finding team] received suggests there was an order [to] kill Munir before the presidential elections. The political dynamics around the elections could be an important factor in the explanation of his death…. In the beginning I didn’t know what [the order] meant, but after comparing other facts, it became clear that his murder relates to the elections.’ Munir staunchly opposed all military influence on those elections. Most candidates had some military connection. In the first round, held in July 2004, Munir’s campaigning helped to narrowly eliminate retired General Wiranto. Academic Amien Rais was also eliminated. In the second round, incumbent President Megawati faced off against retired Lieutenant General Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, her former coordinating minister for political and security affairs.

Among Megawati’s many military supporters was retired Lieutenant General A M Hendropriyono. He had been one of her closest confidantes since the early 1990s, and when she became president in 2001 she appointed him head of BIN. Human rights activists protested the appointment. Hendropriyono was still with the infamous Kopassus special forces when, in 1989, he led an attack on a dissident Islamic farming community at Talangsari in southern Sumatra. By one account this left 246 men, women, and children dead. Hendropriyono was Muchdi’s superior at the time of Munir’s death.

Contrary to the popular perception of a clean officer, Yudhoyono’s career is not free of human rights concerns either. In 1999 he was chief of territorial affairs at TNI headquarters, reporting directly to armed forces commander General Wiranto. He coordinated all Indonesia’s territorial commands, including the Udayana Command that terrorised East Timor in 1999. Working behind the scenes, he thus shared command responsibility for the atrocities committed against civilians after the pro-independence vote of 30 August 1999. In June 1999, according to the book Masters of Terror [ see review - ii91: Jan-Mar 2008 ], he rejected the concerns of the Australian Defence Force chief, Air Marshal Doug Riding, who had come to talk about the TNI backing for the East Timor militias. Riding warned Yudhoyono and other officers that ‘the most significant threats to a genuinely free ballot come from the pro-integrationist militia groups, supported by TNI.... This is very seriously damaging the credibility of the Indonesian Government and TNI.’ Yudhoyono merely remarked that disturbances to that point had been minor. Afterwards, he defended the TNI against allegations that it had committed crimes against humanity by presenting what had happened in East Timor as far less serious than Rwanda, Bosnia or the Nazis in World War II. ‘There is a conspiracy, an international movement... to corner Indonesia by taking up the issue’, he said. His name had earlier been linked with the military attack on Megawati’s PDI-P headquarters on 27 July 1996, when he was chief of staff of the Jakarta garrison. This attack left five dead and 23 missing.

Munir prophetically told the Weekend Australian in June 2004 that, if elected, Yudhoyono would be likely to quash efforts to bring military offenders to justice for past atrocities

In 2004, human rights activists most feared a Wiranto presidency. But Munir did not speak out only against Wiranto. While at times appearing to endorse Yudhoyono’s promise of sounder economics, Munir more often cast doubt on his human rights record. He prophetically told the Weekend Australian in June 2004 that, if elected, Yudhoyono would be likely to quash efforts to bring military offenders to justice for past atrocities. In Indonesia the president was in a ‘very strong position to decide whether atrocities from the past should be heard in a human rights court or not,’ he said. Munir also recalled Yudhoyono saying in 1997 that there was nothing wrong with Suharto's New Order regime.

Indeed, in January 2004 the state news agency Antara quoted Yudhoyono, then still the security tsar, as telling hardline military officers: ‘Democracy, human rights, concern for the environment and other concepts being promoted by Western countries are all good, but they cannot become absolute goals because pursuing them as such will not be good for the country.’ Yudhoyono did nothing during his first term in office to dismantle the territorial system that lies at the base of the military’s continuing political influence. Ever the smooth talker, SBY remarked shortly after Munir’s death: ‘He was a critical, staunch figure. Sometimes his criticism made many ears redden. He criticized the Indonesian military, and, often, me. But we need a person like Munir to remind us if we stray away from democracy.’ An impartial observer might add: ‘We also need Munir’s murderers prosecuted.’

It is possible that Yudhoyono’s massive victory at the polls – 60.8 per cent in the first round of a three-horse race – will empower him to tackle the hard issues, including the Munir case. Following the April 2009 legislative elections, his Democrat Party has 150 seats in parliament – the biggest single block. Tim Lindsey says: ‘There is a possibility Yudhoyono will be different in his second period as president; he will be much less cautious and take risks. With his party majority in the parliament, he will be less obliged to compromise with other parties.’ It is his last chance to make a difference to human rights in Indonesia. He is constitutionally limited to just two terms.

Earlier self

But he could also now revert to an earlier self. Veteran journalist John McBeth writes that SBY has changed over the last five years: ‘He listens only to a few selected people. Before, he listened to a wide range of opinions.’ Besides his wife, Ani, and her mother, Sunarti Sri Hadiyah, he relies heavily on two close mates from his active service days. One is his cabinet secretary, retired Lieutenant General Sudi Silalahi; the other his head of household staff at the palace, retired Major General Setia Purwaka. His new vice-president, Boediono, is an apolitical academic who will advise rather than act independently as Jusuf Kalla did.

Unless SBY acts now, he will simply confirm the growing suspicion that, but for the two-term limit, he would not mind becoming another Suharto

All this suggests that Yudhoyono is unlikely to reopen the Munir case without stronger international pressure. Over the last few years Munir’s widow Suciwati and Kontras coordinator Usman Hamid have lobbied parliamentarians overseas to do exactly that. They addressed the Australian national parliament in February 2007. The response was weak. One senator (Ruth Webber, Labor, Western Australia, since retired) wrote to the Indonesian ambassador in Canberra asking mildly for an ‘independent team’ to investigate the murder. She issued no press release, and received no reply. Australian Foreign Affairs Minister Stephen Smith told Sydney-based NGO Indonesia Solidarity in a March 2009 letter it was ‘inappropriate to comment’ as it was an Indonesian affair.

Munir’s ghost will continue to pursue Indonesian presidents until those who ordered his murder are brought to justice. Unless SBY acts now, he will simply confirm the growing suspicion that, but for the two-term limit, he would not mind becoming another Suharto. ii

Setyo Budi (budi@infoxchange.net.au) is a freelance journalist in Melbourne. He was brought up in Semarang, and has focused on human rights reportage about Indonesia and East Timor.

See also 'The one that got away' [ii94: Oct-Dec 2008] by Tim Lindsey & Jemma Parsons