Hearing about my mother's experiences in May 1998 became a pivotal moment that has shaped my life.

Alvino Kusumabrata

‘Every second, I feel the bitterness’, my mum said. She tried to remember clearly what happened 26 years ago in May 1998. When she recalled something about that event, her forehead wrinkled with distaste. Her facial expressions couldn't deceive me. Despair, fear and feeling threatened seemed to merge into one. Such sentiments only surfaced when remembering the tragedy.

‘It had become a habit for students to rotate protests between universities in May,’ Mum continued, ‘but after the Trisakti Tragedy, all students became unified to rally together'.

One day, my mum – a student at that time – was attending class as usual. ‘My feelings were uneasy, as if something was about to happen’, she confessed. Suddenly, there was a great uproar on the highway, disrupting the ongoing class atmosphere. The classroom became noisy. There was no choice for Mum's lecturer at that time but to stop the class.

Confused, my mum tried to digest what was happening. She looked out the window to see what was happening on the street. ‘A wave of people united like ant soldiers,’ Mum reminisced. Within a few hours, the most tragic riot since mass-killings in 1965-66 unfolded once again.

People began randomly looting Chinese Indonesian-owned stores. From one looter to another there was a common sentiment binding them: they were anti-Chinese. They didn’t care about morals as long as their hatred towards the Chinese Indonesians remained ablaze. They entered the stores and shamelessly came out carrying full crates of food and drinks. Getting home from the campus became a serious challenge for Mum who had to take cover from flying rocks and tear gas. The mother was beset by fear of being hit by stones. She took short steps, then hid among the buildings and houses. She continued doing that until she reached home. ‘People became demons at that time,’ she said.

Looting was the beginning of a series of more horrifying events, including the persecution of Chinese Indonesians. Persecution is the culmination of anti-Chinese sentiment in Indonesia solely because they are rich. Their prosperity has become a scapegoat justification perceived as the source of oppression towards non-Chinese Indonesians. Generally, such sentiments are held by non-Chinese Indonesians, but then peaked during the 1997-1998 monetary crisis. Chinese descendants were raped and intimidated by those who called themselves ‘pribumi’ (natives). Mum knew all of this horror through neighbourhood rumours. However, the response of Mum's environment seemed to imply support for the persecution. One concrete form of this was support for the looting by hurling insults at fellow communities, specifically among Mum’s neighbourhood units (in Indonesian terms, we call it RT or Rukun Tetangga).

The tragedy happened decades ago, but it has forever shaped my mother, myself and the city we call home. Through Mum's personal experience, I expand my lens to further examine how the 1998 Tragedy shaped subsequent generations, specifically the post-1998 generation.

The formation of us

My mum’s story became the pivotal moment of awareness that has shaped my life. However, long before Mum enlightened me by recounting one of her authentic experiences, my interactions with the city were not entirely honest. That relationship was established through education.

I grew up from childhood to adolescence in the southern outskirts of Solo. The Javanese cultural world surrounded me at every step. One of the Javanese sayings that I have embraced since childhood is the expression ‘Sing wis, ya wis’ (let bygones be bygones) and ‘Sing wis lungo, lalekno’ (what’s done is done, let it be forgotten). These sayings maintain the tradition that something that has occurred—usually something depressing—doesn’t need to be brought up again in today’s conversation. Without realising it, that saying has been subtly integrated into my educational upbringing.

Entering junior high school opened up new possibilities in my life. I was grateful to meet like-minded people who enjoyed discussing literally anything critical, particularly when it came to history, politics and society.

At that time, I admired one figure, Sukarno. His progressive left-wing thoughts fascinated me and prompted me delve more deeply into the wider history of the leftist and nationalist movements in Indonesia. My introduction to Sukarno's stature first occurred when reading the essay, ‘Nasionalisme, Islamisme, dan Marxisme’ (1926) during my third year of junior high school. It is no exaggeration to say that I am very grateful to Sukarno for helping me to enjoy historical issues.

My interest in national history led me to delve deeper into local history, particularly in Solo. Why? I recalled the statement of a friend-cum-activist: the nerve centre of Indonesia’s movement is in Solo. I was intrigued and wanted to examine this idea more deeply. The historical dynamics of the movement in Solo are older than this Republic. Events in Solo have brought colour to Indonesia at large, from the seeding of Marxism through strikes by trade unions and batik traders by Sarekat Rakjat (1920s), to the anti-Swapraja movement (1945-46), and until the Reformasi (1998).

Discussions about history became more engaging during ninth grade. From my teacher’s presentation of various chapters of historical material, I was particularly captivated by the Reformasi. Honestly, I knew little about this chapter of Indonesian history. That day, as usual, my teacher was explaining the history of the Reformasi in front of the class and I paid close attention, eager to learn more.

Nothing grabbed my attention until my teacher said, ‘Solo played an important role in this history. Solo behaved like the evil Anoman character in the Anoman Obong play'. My eyes, which were dim, then widened. What happened? I had read the Ramayana comics by R. A. Kosasih, but Anoman didn't misbehave. My teacher didn't continue to the conclusion, but left it hanging. My friends didn't have the initiative to respond because the boring teaching methods in history class suppressed curiosity. I had to do the task. My teacher glanced at me for a moment. Then he said, ‘It's not time for you to know yet'. Then the teaching stopped. The material soon shifted.

Entering high school, the discussion about the Reformasi was just a repetition of junior high school material. The contents only emphasised the victory of civil society over Suharto's authoritarianism. My history teacher did not cover the complexities of that event (described by Mum) in Solo. There was no mention of Solo as a catalyst for the event. The reason my teacher didn't explain (intentionally or unintentionally) the 1998 tragedy was due to the lack of information in the existing textbooks.

The pattern remained consistent from junior high school to high school. Dialogues to uncover the darkness behind the Reformasi never occurred even until I had graduated.

Frankly, my curiosity was tormented. I had to know the truth about what happened in Solo in May 1998. Rummaging through dusty local newspaper and magazine archives at the local library and at my grandparents’ house, I found the answers I had been searching for. Fortunately, my grandparents subscribed to magazines and newspapers from their youth until old age.

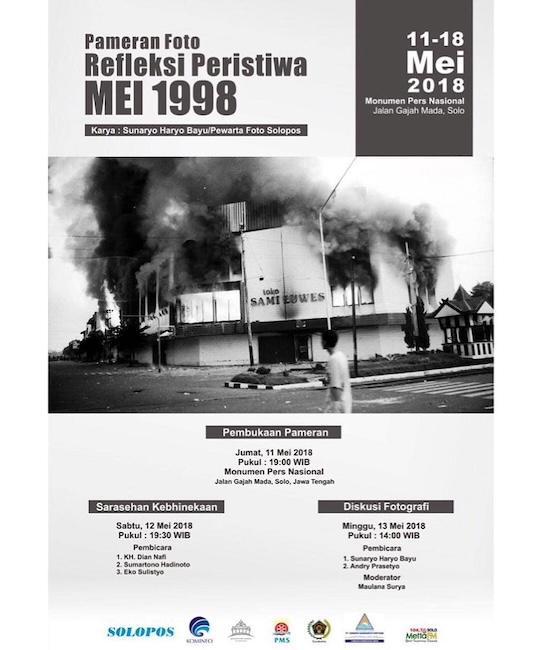

Here’s what happened: The anti-Chinese riot began on 13-14 May 1998 in Solo, Jakarta, and several other cities. Initially, in Solo, looting of Chinese-owned stores occurred, but eventually expanded to include murder, rape and arson. According to Mum, some residents in Solo had to put up large boards on the village gates that read, ‘Milik Pribumi’ (Owned by Natives) to avoid the mob's rampage. ‘Imagine. It went to that extent. The individuals inciting the riots only saw things in black and white. If the word 'pribumi' was on a building, it was protected. If not, it became a target of looting', Mum said.

Sinologist Leo Suryadinata, who has studied the dynamics of Chinese-Indonesians extensively, including their traumatic experiences during the 1998 Tragedy, wrote in the Special Report by TEMPO edition of 16 August 2004: ‘Those [Chinese people] who were capable, had fled abroad, but the majority remained in Indonesia. The Chinese community was generally confused, if not desperate.’

Reading one report after another left me continuously astonished. My peers who had also grown up in the post-1998 generation, like me, had no known way of gaining this historical information. I had to fight patiently and fiercely the dust sticking to the archives, just to read it. In short, reading those reports was a privilege. It had to be fought for to gain complete knowledge – without any sugar coating, all because my formal education did not provide access to it.

Those facts then gave me cause for contemplation. The suppression of historical knowledge nurtured by my teachers and the absence of conversations about the 1998 tragedy formed a sad post-1998 generation in Solo. However, the post-1998 generation certainly has the right to know the history of their own identity – as part of their fundamental right.

The post-1998 generation never really knew the history of their city from history education. Instead these stories were passed down orally through families, but they were done so more as warnings or families simply reminiscing. The main stories came from families as the witnesses or actors in history, often accompanied by myths. Generally, the story archive from family experiences to my peers had to be taken with a grain of salt.

The level of subjectivity of the stories told by families or individuals need not be questioned. Typically, in my observation, my peers never question or criticised their parents’ oral traditions for one reason: fear of kualat (the Javanese term for accursed). Generally, they do not question what their parents say, regardless of whether it is true or not. Furthermore, the narratives surrounding the May 1998 tragedy in Solo have been shaped by those who were involved, particularly the civilian perpetrators who are now parents. Their viewpoint is deeply rooted in our shared recollections, unchanged despite the passage of more than 25 years since the Reformasi era began, appearing enduring and unapologetic.

‘The Chinese people were stubborn, causing the economy of our family to collapse', said my friend’s parents. My friend, of course, believed his parents' story. There is no doubt that the family still believes their economic turmoil was due to the behaviour of the Chinese people during the twilight of the New Order.

This negative perception towards Chinese Indonesians persists in my social circle – reflecting broader societal attitudes. It's no longer considered taboo to talk about it, highlighting the prevalence of negative stigma towards people of Chinese descent. The prevailing social inequality often serves as the root cause for the dynamics witnessed in our community. In Solo, for example, there exists a stark contrast in social standing between the Chinese descendants and my own social circle. This social divide is evident and undeniable creating a palpable barrier between the two groups.

This division reflects the lingering effects of the 1998 tragedy where negative sentiments towards the Chinese community persist among my peers, shaping the attitudes of the post-1998 generation. Despite hoping for mutual acceptance, my friends often find themselves criticising the Chinese community instead. This irony underscores the lasting impact of historical events on contemporary social dynamics.

I recall a particular instance where I engaged in what could be described as a 'brief lecture' on Reformasi with one of my friends, whom I regard as particularly knowledgeable in history. At the conclusion of our discussion, I posed a poignant question: whether Chinese people’s persecution was justified. My friend's immediate response was affirmative and he cited recent concerns about potential Chinese dominance in our country's affairs. He further expressed apprehension about our local products being overshadowed by those of Chinese Indonesians.

Hearing his answer left me silent and stunned.

Knowledge gaps

The educational shortcomings in teaching Solo's history apparently contributed to misunderstandings among the post-1998 generation. I know for certain that hardly anyone in my friendship group knows about the 1998 tragedy in Solo. Even if they understand, the understanding is still vague.

A few days ago, I randomly interviewed young people in Solo. From several questions I asked, generally they didn't know that the Reformasi had arisen in Solo. Furthermore, they were quite surprised when I mentioned that there had been incidents of persecution against Chinese Indonesians. In conclusion, the dark history of this city has never been seriously revealed in the education system.

I understand the good intentions of my teachers who tried to tightly apply closure to that time in history. Actions to hide the blemishes ‘for safety’ backfired for the generation consuming that history education. The agendas in history education, including broader curricula, still selectively choose historical content to teach.

In the context of history education, students should thoroughly study what is considered 'good history' – leaving aside what is considered 'bad history'. Ideal pride in Indonesian historical epics, such as victory against colonialism, the Proklamasi, and the 1998 Reformasi, have been deeply ingrained. Conversely, based on my experience studying the rigid substance of Civic Education and Pancasila education, ‘bad history’ like the persecution of Chinese Indonesians in 1998 and the intellectual genocide of leftists (1965-66) are, in fact, left out. Simply put, because it would injure the greatness of Indonesia or Pancasila, our guiding principles, which were so meticulously ordained by the founding fathers.

Knowledge about what really happened in 1998, especially in Solo, has never been black and white. The spotlight of history has always focused only on glorifying the downfall of Suharto's New Order cronies. Throughout my education, discussions about the violence of the 1998 events in Solo were never combed through – not even once. It was faint and muffled.

Such an orientation in history education has been in place since the New Order came to power. Tight censorship and the selection of historical materials deemed ‘necessary’ were prevalent, for example there has never been a specific chapter to explain about the mass genocide against suspected and/or communist individuals in 1965-66. The realisation of a bleak post-1998 generation makes me recall my friend's Facebook status: ‘not until 2045, the centennial celebration of Indonesia's independence, perhaps Indonesia would have ceased to exist.’

Considering all of that, in this case, the post-1998 generation in Solo can be categorised as victims. Victims of a history curriculum based on nationalist slogans. Access to a comprehensive understanding of history is deliberately restricted. As a result, history education fails to provide the framework necessary for the post-1998 generation to fully realise their right to know. Instead, what prevails is a lack of awareness about one's own identity.

The hope of the post-1998 generation is simple: Provide genuine history education that provides inclusivity without marginalising a particular event. Also, discussion spaces should naturally grow from there. Face-to-face, open and conversational encounters between the post-1998 generation and those who were either perpetrators or victims of history. Our generation needs to listen to a larger portion of the voices of the victims. Our generation is tired of partial oral history and history education that closes off discussion spaces. Being open about our history, will allow our generation to grow with less prejudice against other groups.

Epilogue

The efforts of the Solo City government to bring inclusivity, one of which is the sparkling lanterns decorating the sky above the Pasar Gede Bridge during Chinese New Year, seemed futile. Last Chinese New Year, my friends invited me to hang out around there. One of my friends was the same person who enjoyed mocking Chinese people. Yet, he enjoyed the atmosphere full of red attributes.

This is how we were formed. Some of our generation never knew what happened in Gladag, Laweyan, Pasar Kliwon, Coyudan or Slamet Riyadi Street in May 1998. Some of us never even knew there was modern persecution to give birth to the Reformasi. Some of us never knew that elderly Chinese Indonesians living in Solo hold unresolved traumas. On the other hand, some of us – even if we know – care less about that trauma in the end. However, most of us continue to grow with latent sentiments towards other groups in the depths of our hearts.

One of my friends will always complain, ‘Penak dadi wong Cino, iso foya-foya' (It's comfortable being Chinese, as we are able to live extravagantly).

The outside had turned dark and the Maghrib call to prayer was heard. This marked the end of my light conversation with my Mum. Just before ending our talk, she asked a question: ‘Sentiments like these aren't good. Tragedy could happen again, just if it remains like this; as it did in 1998, right?’

Alvino Kusumabrata (alvinokusumabrata2017@gmail.com) is an undergraduate student in the Faculty of Law, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta, and a writer whose work has appeared in IndoPROGRESS and Tirto. This essay is part of our series of works written and edited by young people.