Charlotte Papillaud Looram

Salvaged near Belitung Island off Sumatra's southeast coast in 1998, the Belitung is Southeast Asia’s most notorious shipwreck. As the first known sewn-plank vessel in the greater Indian Ocean, and containing the largest and most intact assemblage of ninth-century Tang Dynasty ceramics, gold and silver, it is of incredible significance to the study of medieval Southeast Asia.

It was, however, the process by which the ship was salvaged from the sea floor that is a more likely explanation for the Belitung’s notoriety. At the time, the decision was made for the shipwreck to be commercially salvaged – a fact that sparked major controversy during its first major international exhibition. The practice is widely condemned by the maritime archaeologists as ‘destruction in the interest of profit’, and critics worried that the exhibition, which was supposed to be held at the Smithsonian no less, would be understood as tacit support and endorsement.

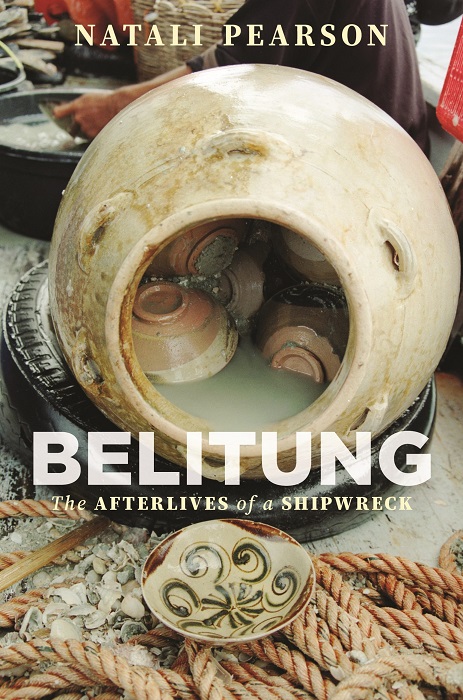

Natali Pearson does not shy away from such issues in this comprehensive account of the Belitung as a ship, a wreck, a commercially salvaged treasure, and a museum collection. Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck recounts its journey from the Indonesian seabed to Singapore’s Asian Civilisation Museum, while also grappling with notions of ethical protection and preservation for transnational underwater cultural heritage.

Pearson highlights how that the location of the sinking of the Belitung in Indonesian waters, has had important repercussions on the way we understand the shipwreck, and also international and institutional standards and ideals about underwater cultural heritage. By following its ‘afterlives’ across various social, cultural, institutional, and political settings, Pearson demonstrates the way the ship and its story are ‘a product of contemporary influences, rather than ancient’. Each chapter describes a different afterlife as the ship was ‘Created’, ‘Wrecked’, ‘Provenanced’, ‘Contested’, and ‘Reimagined.’

The first three chapters provide a sweeping exploration of debates around the ship’s origin and trade route, of the political and regulatory environment it found itself in at the time of its discovery, and of the salvage process, including new insights gleaned from interviews with the people who were involved in its salvage, sale, and display. The final two chapters and the conclusion are the real strength of the book, in which Pearson untangles the way competing claims over the ship, and the scandal of the commercial origin of what would become a museum collection, have had a critical impact in shaping the story of the Belitung.

Typically told, the story of the Belitung ship is one of connecting East and West: a story of trade between the Tang Dynasty in China and the Abbasid Dynasty in West Asia, in which Southeast Asia is merely a stopover. The shipwreck is a testament to the complex web of connectivity traversing the Indian Ocean in the ninth century: a ship built of African and Indian timber using a construction method from Arabia or the Persian Gulf, carrying a Chinese cargo intended for a Middle Eastern market. Some might say, how lucky for Southeast Asia that the ship sank off the coast of an Indonesian island or it would barely feature in the story at all. Except, as Pearson argues, it is not luck at all, but a consequence of Southeast Asia’s central role in global maritime histories. To frame it as luck is to render Southeast Asia broadly, and Indonesia more specifically, a passive actor in these histories. At the core of this book is her belief that Indonesia has the strongest claim on the ship, and it is clear that Pearson regrets the state’s decision to sell the collection to Singapore and the lost opportunity to tell Indonesia’s story as ‘Southeast Asia’s true maritime centre.’

Following the salvage of the shipwreck, the Singapore Tourism Board purchased the collection despite having a more tenuous claim as the ship’s ‘natural home’ than Qatar and China who had also shown strong interest and could be considered, respectively, the ‘East’ and ‘West’ of the Belitung story. There was nothing in the Belitung, the cargo, nor the speculated trading route, that explicitly linked Singapore to the shipwreck and it would struggle for years to find a way to present the collection and justify its US$32 million price tag. Through clever marketing and curation, it was eventually integrated into the ‘Singapore Story’ as a representation of the city-state’s position as a fulcrum of ancient and contemporary maritime trade and renamed the ‘Tang Shipwreck Collection’, erasing Indonesia from the story all together.

Pearson’s in-depth account of Singapore’s efforts to insert the ship into the Singapore Story demonstrates the way they also legitimised the objects as museum objects following the scandal of the cancelled Smithsonian exhibition. In 2013 the collection was transferred from the tourism portfolio to the heritage portfolio, and then in 2015 placed on permanent display at the Asian Civilisations Museum. Since then, the objects of the Tang Shipwreck Collection have been loaned out for international exhibitions such as Aventuriers des Mers: De Sinbad à Marco Polo in France, 2016; Secrets of the Sea: The Tang Shipwreck in Korea, 2018; and The Baoli Era: Treasures of the Tang Shipwreck Collection in China, 2020. These exhibitions at esteemed institutions are slowly erasing any commercial connotations and associations, and establishing the Belitung artefacts as heritage objects.

The question of how, or indeed whether, to exhibit commercially salvaged heritage is an important thread in the Belitung’s continuing story. Pearson deftly navigates the controversy. She agrees with criticism of the chaotic way it was conducted and the resultant loss of knowledge for such a significant shipwreck, whilst arguing that the response also betrayed a fundamental misunderstanding of the Southeast Asian context, which she characterises as having ‘undertones of colonialism, cultural elitism, and Eurocentricism.’

When the Belitung shipwreck was discovered in 1998, Indonesia’s policy regarding historical shipwrecks was to employ commercial salvage companies to recover the objects through the use of a permit that required that the hull be left in-situ for potential future development, and gave Indonesia ownership over 50 per cent of the salvaged objects (or more often, 50 per cent of the proceeds of the sale of the objects). This was, she argues, the best option available in this particular social, political and institutional context, and ultimately ensured this specific shipwreck’s preservation.

This point is important. It highlights the way local knowledge and expertise is too often dismissed and Southeast Asian actors held to an impossible standard by Western institutions. Pearson’s treatment of the Belitung case perfectly encapsulates the complexities of managing underwater cultural heritage. As it often exists over multiple jurisdictions and speaks to the histories of multiple nations and cultures, as well as their visions for the futures, underwater cultural heritage is at the centre of international debates on who owns and is responsible for heritage. Being underwater, it also requires resources to excavate and conserve, but also monitor and police, that few states have access to. We would do well to remember, as Pearson points out, that ‘good archaeological practice does not take place in a void’, and that flexible thinking is necessary when it comes to heritage that exists in the churning and ever-changing context of the ocean.

Throughout Belitung: The Afterlives of a Shipwreck Pearson tells an alternative story of the Belitung ship that goes beyond the narrative of a physical manifestation of East-West connectivity. Pearson re-centres Indonesia and Southeast Asia in the story of the Belitung, and more importantly in international discussions surrounding underwater cultural heritage. This book is a call to action for maritime archaeologists and museum professionals to reassess our frameworks and mechanisms regarding trans- and pre-national heritage, to be more conscious of the power relations that go into maintaining them, and to be open to alternatives modes of thinking.

Natali Pearson, Belitung: The afterlives of a shipwreck, Honolulu, University of Hawai’i Press, 2022.

Charlotte Papillaud Looram (cplooram@gmail.com) is a researcher currently undertaking a PhD at the University of Western Australia Law School on the trafficking of transnational heritage such as underwater cultural heritage.