When I used to teach demography and statistics in Australian universities in the 1970s and 1980s, I would have my students look at the statistics of Indonesians in Australia. They were always surprised that despite the White Australia policy, which continued until Whitlam took office in 1972, there appeared to be thousands of Indonesians in Australia in the 1950s and 1960s. The explanation lies of course in the Australian Census asking for ‘Place of Birth’ and the reality being that virtually all these ‘Indonesians’ were in fact Dutch emigrants who had been born in the Dutch East Indies and came to Australia after Indonesia gained its independence in 1949.

As illustrated by the book under review, Renée Belloni’s The Sun in His Eyes (Senang, 2024), many thousands of Dutch came to Indonesia during its 350 years of colonialism, married local Indonesiansand their descendants formed a large and thriving ‘mixed-race’ population in colonial Indonesia. These people were variously described as ‘Indisch’, ‘Indo’ or ‘Eurasian’. Neither wholly Indonesian nor Dutch, they nevertheless often felt that the country was their ‘homeland’, having been born there and frequently being the fourth or even fifth generation to live in Indonesia.

This situation continued until the Japanese occupation of 1942 and the subsequent 1945-1949 Indonesian independence struggle. Seen as neither Dutch nor Indonesian, they were consigned to a situation where they lost their ‘homeland’ and any security of existence. Many were incarcerated in camps by the Japanese, and like the whole population, faced repression and starvation. The Japanese defeat, and subsequent declaration of independence, resulted in The Netherlands moving to militarily suppress the new republic. In this situation, mixed-race Indonesians were not trusted and perceived as being on the side of the Dutch, and faced existential insecurity as the result of widespread massacres. Many chose to migrate to the Netherlands, where they could settle as Dutch citizens, though in cold and alien Holland they often faced racial discrimination and poverty.

In contrast to Dutch colonials fleeing Indonesia after independence, the White Australia Policy prohibited mixed-race Indonesians from migrating to Australia. One other avenue of escape was to go to West Papua, the last remnant of the Dutch East Indies. This territory remained under Dutch administration until 1962 when ‘West Irian’ was handed over to Indonesia.

What was colonial life in Indonesia for these mixed-race families caught between two worlds? Up to now, the reality is that very little has been recorded of what their lives had been like, despite the fact that mixed-race families had lived throughout colonial Indonesia for hundreds of years. It is the mission of Belloni to encourage the descendants of families such as hers to chronicle these lives before they are lost. The Sun in His Eyes is the result of her creative effort to do this. Belloni now lives in Australia having married an Australian, and so her life and the life of her family, form part of the rich multicultural background of our population. Her work recalls the same way that the artist and scholar, Frances Larder paved the way of creatively bringing into Australian consciousness the rich tapestry of Indonesian heritage that Dutch emigrants have brought to this country. It should be noted that Larder in fact chose tapestry as a medium to illustrate this before documenting it in her scholarly and fascinating Master’s thesis.

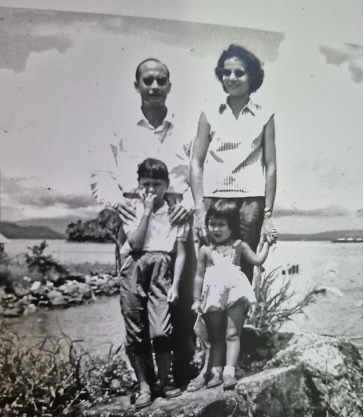

Renée Belloni’s book focuses on Claude Belloni, her father, whose life was nothing less than fascinating. Conscripted as a teenager into the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL) just prior to the Japanese invasion, he spent the first part of World War II in Japanese prisoner of war camps, before being transported by ship to Japan as slave labour. However, the ship in which he was being transported was sunk by the Allies. He was one of the few to survive this horrific event, which is portrayed on the cover of the book. He ended up as one of thousands of forced labourers for Mitsubishi in Nagasaki, and then experienced the devastation caused by the atomic bomb dropped on that city in 1945. His life continued to face challenges. On his return to Indonesia, he found he had not been discharged from KNIL but, rather, was required as a member of the colonial forces, to fight for the Dutch against the Indonesians. Eventually, he and his family ended up in West Papua, where among other adventures, he helped New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller search for his son Michael when he was lost there in 1961 on an ethnological expedition.

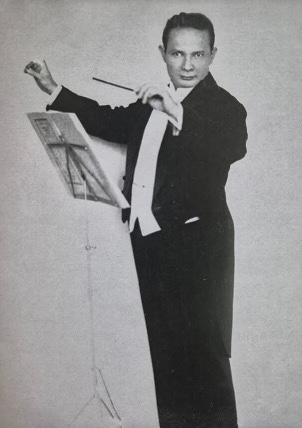

Eventually, the Belloni family was forced to migrate to the unwelcoming Netherlands, a cruel shock for someone who had spent his life in the tropics. The fact that Claude kept a diary throughout his life enabled his daughter to vividly chronicle both his daily colonial Indonesian existence as well as momentous experiences including being shipwrecked and the fallout from an atomic bomb. Through the life of her father, Belloni also opens up to us the world of mixed-race Indonesians in the centuries of colonialism. Her family’s history in Indonesia dates from 1835 when Jen Baptiste Belloni Jr, her father’s great-grandfather, originally from Belgium, arrived in Java. He subsequently settled in Sumatra, where he married a local woman, Nasari, with whom he had six children. As one can imagine, the numbers of descendants of this family proliferated over the years. Of particular interest is the life of Claude’s father, Fred Belloni, a noted violinist and composer.

Fred Belloni was feted in many parts of the world, including the Netherlands, as well as in his Indonesian homeland. His compositions, recorded by Columbia and sold as 'Belloni Records' were strongly influenced by such elements of Indonesian music as kroncong. In London he was invited to conduct the Columbia Symphony Orchestra.

Belloni’s book was first published in Dutch. Now she has rewritten it in English, opening up the world of colonial Indonesia to an Australian readership that is becoming increasingly aware of the kaleidoscopic nature of its immigrant population’s multicultural heritage. One might note that she has chosen to write it in what can only be called colloquial English, a refreshing change from dour scholastic expression. Her adventurous father would no doubt be proud of the way in which his daughter has paid him homage and opened their family’s rich history to Australian and Indonesian eyes.

Ron Witton (rwitton44@gmail.com) gained his BA and MA in Indonesian and Malayan Studies at the university of Sydney and his PhD from Cornell University. He has taught in universities in Australia, Indonesia and Fiji. He still works as an Indonesian and Malay translator and interpreter.