Though characterised by autocracy and authoritarianism, political dissent found a place in the cinema of the Sukarno and Suharto eras

David Hanan

Since the end of Suharto’s New Order regime there has been considerable growth in overt political activism in Indonesia—including by a cohort of independent filmmakers. Aspects of these developments in Indonesian film culture are documented in this edition of Inside Indonesia. Contemporary filmmakers have the advantage not only of more openness in Indonesia, but of using cheaper and more efficient kinds of technology than was available during the Sukarno and Suharto periods.

In the nearly five decades of independence prior to President Suharto’s demise, expressions of markedly dissenting political views on film amount to a significant, if small, tradition. How this political commentary was achieved in the midst of authoritarianism was determined by a combination of available commercial frameworks, technology and costs. During these five decades, ‘filmic activism’—or the capacity of film to raise important human rights and social issues—primarily took place within the framework of the commercial film industry.

An early, critical lens

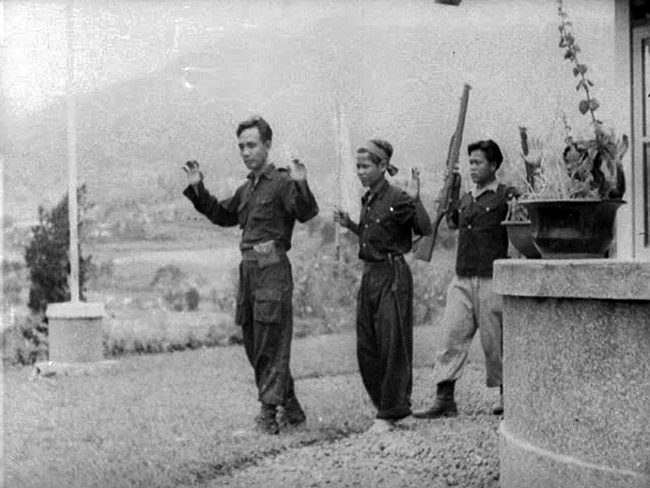

Usmar Ismail is considered the pioneer of Indonesian cinema. The first feature film made by his newly established Perfini Company, in 1950, Darah dan Do’a (‘Blood and Prayer’, aka ‘The Long March’) shows—via a flashback in its first few minutes—members of the Indonesian National Army (TNI) shooting dead young members of the PKI (Indonesian Communist Party). Their hands raised in surrender, the killings took place in the midst of the left wing rebellion that occurred at Madiun in East Java from mid-September to early December 1948, less than 15 months before the film went into production.

In 1948 it was becoming clear that a cold war was developing between the USA and communist nations, not just the USSR, but also China. The stand taken by the Indonesian government against the rebellion in Madiun, including the execution of large numbers of supporters of the left, would be one reason for the USA to support Indonesia in its struggle for independence. Historians see the execution by the TNI of communists and other left wing rebels at Madiun as having political significance at an international level. Darah dan Do’a questions the justice of these executions.

Although key Perfini films were often screened in censored versions on TVRI during the Suharto period and are primarily known for celebrating the years of the Indonesian struggle for independence (using a mode of production influenced by neo-realism), in their uncensored versions they also provide critical perspectives on the period of struggle. A second Perfini film, Lewat Djam Malam (‘After the Curfew’, 1954) at one point shows two Indonesian freedom fighters, at the order of their commander, shooting dead a family of Javanese refugees (parents and children) in order to be able to dispossess them of the goods they are carrying.

Lewat Jam Malam has recently been restored with funding from the National Museum of Singapore and Martin Scorsese’s World Cinema Project, in association with the Konfiden Foundation and Kineforum of the Jakarta Arts Council, using film elements preserved at Sinematek Indonesia. This 103-minute uncensored version, with English subtitles, is available on YouTube.

These two Perfini films, Darah dan Do’a and Lewat Djam Malam, in fact provide significant points of reference in world cinema. Both these films, together with Perfini’s Enam Djam di Jogdja (1951), are known to be influenced by the example of the Italian neorealist films made in the five years or so immediately following the end of World War Two. The similarities relate to their extensive use of non-actors and location shooting, together with very basic black and white ‘newsreel-style photography’ and the frequent drafting of their stories on location. In depicting incidents that show some Indonesian freedom fighters not only confronting Dutch forces and their collaborators, but committing human rights abuses against their own population, these Indonesian films do something that the classic neo-realist films (by Roberto Rossellini for example) never do. The Italian neorealist films depict only ‘black and white’, ‘us and them’ situations, the good freedom fighters versus the Nazis and the Fascists.

Subversive satire

This use of a commercial feature film framework to provide dissenting commentary on political situations is found not only in films depicting the period of struggle for independence, but with films engaging with political situations in the new society. For example, there is the Perfini film Tamu Agung (‘Exalted Guest’, 1955), a satire on President Sukarno’s style of politics and particularly on Sukarno’s tendency to rely on charismatic political leadership as a way of retaining power without proper elections.

More trenchant is Nya Abbas Akup’s quickly suppressed, subversive, satiric comedy film, Matt Dower (1969) which allegorises the take-over of power from President Sukarno by General Suharto that began in 1965. This early Indonesian colour film is set in a mythical seventeenth century Javanese court. In the film the Suharto character is respectfully addressed throughout as ‘Munafik’ (i.e., hypocrite).

Funded by the Indonesian Ministry of Information as one of four prestige productions designed to enhance the development of the Indonesian film industry, Matt Dower was banned even before its release. When the Ministry discovered what the film was about, its colour negative and all official prints were destroyed. The film survives in the form of one black and white print, surreptitiously made from the colour negative before it was destroyed, and, as its writer-director, Nya Abbas remarked to me in 1989, ‘kept under my bed for 20 years’. I have transcribed the dialogue of this film, the single surviving print of which is now held at Sinematek Indonesia. I hope to eventually subtitle a digital copy.

Other outstanding allegorical films with political implications made in a commercial or semi-commercial context include Slamet Rahardjo’s My Sky, My Home (1989), Garin Nugroho’s Bird-Man Tale (2002) and Eros Djarot and Gotot Prakosa’s Kantata Takwa (1990-2008).

Resistance

My Sky, My Home, which focuses on the friendship between a boy from a rich family, and a street urchin, dramatises the poverty that so many Indonesians were living in at the height of the Suharto New Order. The film was withdrawn (in effect, banned) after only a few days commercial release in Jakarta. Nevertheless, My Sky My Home is well-known in Australia, being distributed by AFI distribution from the early 1990s on and used widely in Indonesian classes at Australian schools and universities.

A film initiated only a year later, in 1990, Kantata Takwa, in its unusual style, marks a shift from allegorical narrative to unorthodox, performance-based spectacle, with short intermittent scenes providing parables of numerous abusive situations commonly found in the New Order. The film is based around the subversive ‘Kantata Takwa’ pop concert held in the Gelora Bung Karno Stadium in Jakarta in June 1990, to an audience of some 250,000 young people—starring popular singers Iwan Fals and Sawung Jabo and their musical groups, and with political poetry read by dissident poet and playwright, W.S. Rendra. The film was initiated by dissident journalist/politician, writer-director and musician, Eros Djarot, together with independent filmmaker, Gotot Prakosa, known for his numerous short films and animations. Although Kantata Takwa had largely been edited within six months of the shoot, it was only released in 2008, due to a warning privately issued by Suharto army-general Benny Moerdani—and subsequent financial complications.

Three highly innovative films mark the end of severe repression under the Suharto regime and the need to use allegory to make critical comment. Garin Nugroho’s feature length Puisi Tak Terkubukan (‘Poetry is not Buried’, 1999), the first film to openly and critically engage with the mass arrests—and massacres—of people regarded as communists, by the army under the orders of General Suharto, following the events of September 30, 1965. The film uses the Acehnese poetry of didong, which is chanted by the arrested Acehnese awaiting execution in a prison in order to maintain their spirits before they go to their deaths—just a small sample of the hundreds of thousands of deaths of people murdered at this time.

Going into production at the same time, within 15 months of the fall of Suharto, was the independent documentary, The Village Goat Takes the Beating. Critical of the actions of the Indonesian army and government in post-Suharto Indonesia, Aryo Danusiri’s film was also made in Aceh, but deals with contemporary events. Funded by the Institute for Community Studies and Advocacy (ELSAM), this documentary investigates war crimes perpetrated by members of the Indonesian Army in the province of Aceh, tasked by the Suharto government since the late 1980s to suppress GAM (Gerakan Aceh Merdeka, The Aceh Independence Movement). Largely filmed in secret in the village of Tiro near a mountainous area in Aceh where members of GAM were operating, the film includes lengthy interviews with relatives of those killed by the military, and with survivors of abuse, torture and imprisonment.

Made early in the post-Suharto period and set in West Papua, Bird-Man Tale (2002) addresses issues of Papuan self-realisation, and concludes with actual footage of the funeral of the murdered West Papuan politician and leader, Theys Eluay. Eluay—who was in the hands of the Indonesian army when he died—had earlier been a member of Suharto’s Golkar party, before he came to support independence for West Papua. Shot on video in order to be sure to comply with the two weeks given for on-location shooting in and around Jayapura, Bird-Man Tale marks a transition point between two kinds of technology—from 35mm film to high quality video—and between two kinds of political situation, the Suharto New Order period and the changes ushered in with the departure of Suharto as president. Over the following two decades, in a more open Indonesia, independent political filmmaking using low-cost technology became more widespread.

Across the first 50 years of independence, at different times Indonesian filmmakers were prepared to use film to engage in political critique. For contemporary filmmakers this might be seen as something of an underground tradition. Such work was produced at great risk to the filmmakers and the films themselves. Three of the most important critical films made in the Suharto period were suppressed: the films either destroyed after completion, withdrawn after a brief release, or the filmmakers warned against the film’s completion and release. Filmmakers and their audiences demonstrated an impressively sophisticated understanding of the importance of critique, satire and allegory, elements that are understood equally by the current generation of Indonesian filmmakers.

David Hanan (david.hanan@unimelb.edu.au) is Honorary Senior Fellow of the Asia Institute at The University of Melbourne. He taught film studies at Monash University from 1978 to 2013, and has authored two books on Indonesian film, Cultural Specificity in Indonesian Film: Diversity in Unity (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017) and Moments in Indonesian Film History: Film and Popular Culture in a Developing Society 1950-2020 (Palgrave Macmillan 2021). Many of the films mentioned above, and their political contexts, are discussed in more detail in the second of these books. He is currently editing an updated and enlarged edition of Film in South East Asia: Views from the Region. This updated edition will be published by the Thai Film Archive.