A new artwork holds up a mirror to physical anthropology and its baseless racial categorisations

A new artwork holds up a mirror to physical anthropology and its baseless racial categorisations

Sadiah Boonstra

A timelapse video of a sprouting red bean is accompanied by an Indonesian language voiceover delivered in a soft, fairytale voice : ‘This is about how humans are born, live and die returning to soil. And for the unfortunate ones, to be dug up again before their time to be exhibited to the world as the losers,’ says the narrator with more than a hint of sarcasm.

This is the opening sequence in The Fattest Land at the Fair (2020), a 12-minute video work by Yogyakarta-based artist Syaura Qotrunadha, selected as Artwork of the New Normal (Karya Normal Baru) for the 2020 Biennale Jogja, held online due to COVID-19. The work shows colonial archival materials from the Netherlands and the Papua New Guinea Newsreel from the 1950s. This archival footage is combined with newly-shot film material, live painting and ASMR (autonomous sensory meridian response) sound recordings. The voiceover is supertitled in Indonesian with loan words spelled in their original languages and script (Sanskrit, Arab, English and Dutch), and also subtitled in English. Syaura’s work can be viewed as a critique on the history of physical anthropology, its methods, practices and legacies today.

Physical anthropology in art

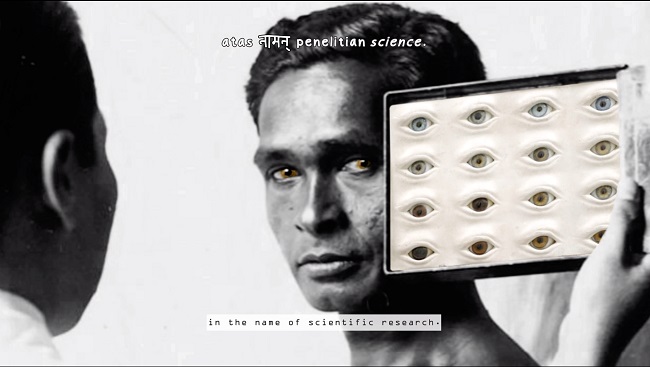

Critique of the study and methods of physical anthropology is the red thread of the storyline. This is illustrated by presenting specific archival fragments of such methods. For example, while the voiceover narrates the lines, ‘the merchants [or the colonisers] marked the captured ones who were still alive, measuring their size and the characteristics of their colour using various instruments’, the viewer sees archival footage of peoples’ measurements being taken.

A prominent source of inspiration for the video work is the study Racial Science and Human Diversity in Colonial Indonesia (2015) by historian Fenneke Sysling. In her book Sysling describes how physical anthropology and its methods studied biological differences and similarities between large groups of people for about a century – from the second half of the nineteenth century to around the mid-twentieth century. Mostly originating from Western Europe and North America, physical anthropologists were interested in the origins and evolution of these groups and hoped to be able to quantify them through measurements.

In the context of Dutch colonialism, physical anthropologists travelled to the Indonesian archipelago to achieve the same goal; measuring bones and body parts, not only of deceased human beings, but also of living Indigenous Indonesians.

The video narrates: ‘They [the physical anthropologists] also made casts of their [Indigenous Indonesians] body parts and collected the bones of the dead people in the name of science’, while the camera shows a close-up of a well-known mask series. These are plaster casts of the faces of forty-two Nias men made in the 1910s by Dutch anthropologist JP Kleiweg de Zwaan (1875-1971). The plaster casts of faces of living people were a part of this process of taking measurements and collecting other data.

As Sysling details in her book, upon his return to the Netherlands, Kleiweg de Zwaan donated the plaster casts he made in Nias and Sumatra to various museums, where they became tangible proof and reminders of the great expeditions and anthropological successes. The masks taught museum visitors how to recognise races through highlighting their underlying coherence, as anthropologists had themselves done in the colony. The plaster casts featured in The Fattest Land at the Fair are currently still on display in the context of the twentieth century history section at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Racial mapping in museums

Syaura’s videowork links museum exhibition practices to the categorisation of people, explaining, ‘In the end, the results of their research, and the body parts, were categorised and brought back into the homeland to be exhibited as proof ….’ This link between the classification of people and the museum goes back to the nineteenth century when it became one of the major institutions enabling the development of new sets of knowledge.

The fields of anthropology, history and art history – among others – selected, ordered and presented objects in such a way that they showed evolutionary and hierarchical sequences of people and history. This particular kind of knowledge-building was facilitated by what sociologist Aníbal Quijano calls ‘coloniality of power,’ meaning a colonial power structure that created social discrimination classifications like ‘racial’, ‘ethnic’, ‘anthropological’ and ‘national’.

Racial categorisations of colonised peoples were visualised and disseminated on maps displayed in museums and exhibitions across the world. The map ‘Peoples of the Netherlands East Indies’ showed in its margins ‘forty photographs of typical heads of the different people of the Archipelago.’ It hung for two decades in the Colonial Museum in Amsterdam – now Tropenmuseum and part of Nationaal Museum voor Wereldculturen (National Museum for World Cultures). From the 1920s until 1948 this map outlined and visualised the racial classifications of Indigenous Indonesians and of geographical regions of Indonesia for the Dutch museum visitor.

A similar map of Indigenous Indonesians in the archipelago was painted by Mas Pirngadie (1875-1936) for the Koninlijk Bataviaasch Genootschap van Kunsten en Wetenschappen (Royal Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences) in Jakarta. The map depicted seventy-eight individuals, each wearing particular cultural attributes representing a specific tribe of the Indonesian archipelago. From historian Marieke Bloembergen’s Colonial Spectacles. The Netherlands and the Dutch East Indies at the World Exhibitions (1880-1931) (2006) we learn that Pirngadie’s work was first exhibited at the Dutch Pavilion at the 1931 Colonial Exhibition in Paris. It was intended to show off the greatness of the Netherlands as a colonial nation to millions of visitors, disseminating the racial categories visualised in the map to a global audience.

Although Pirngadie’s original work was destroyed in a fire at the Dutch Pavilion, another version of this map has been and still is on display at Museum Nasional in Jakarta since 1935. Just short of a century this map of ‘ethnic groups’ is exhibited without accompanying historical information or any other contextualisation up until this day. An informative video on the 2018 restoration of the map, explains to the viewer that the map is a representation of ‘the accessories and facial characteristics of ethnic groups,’ an explanation that confirms, continues and re-authorises colonial racial classifications of people and geographical regions to museum visitors today.

Unmaking racial categorisations

Syaura acknowledges that racial classifications have a continuing influence despite the fact that neither race nor ethnicity can be traced in the human genome, ‘Although the search of body purity is considered irrelevant now, various myths and beliefs that were created in Nomad’s Land still spread for generations.’ The artist counters the methods of physical anthropology by juxtaposing them with the customs of the Indigenous Indonesians they have been practiced on: ‘Originally, beheadings and skull collecting have been a tradition and a symbol for many groups of people around the world. There are groups of people that have been doing this tradition to honour their ancestors.’

In the videowork Syaura also points out that physical anthropologists never found proof for their racial categorisations, ‘After thousands and millions of bodies collected, the merchants finally realised that the purest physical form of humans will never be found, until the end of time.’ To offer a solution for the future, the artist suggests, ‘Perhaps it is time for them [the former coloniser] to start an even dialogue, as all of us will die and become soil at the end.’

Sadiah Boonstra (sadiah@sadiahcurates.com) is an independent curator and researcher based in Jakarta. Her professional and research interests focus on the legacies of colonial history, heritage and arts in contemporary Indonesia.