Nickel’s ‘green development’ boost to resource nationalism

The global energy transition is disrupting old fossil fuel industries, including coal mining, power, and exports. On the other hand, resource-rich countries stand to benefit from a new rush for ‘energy-transition minerals.’ Across the world, this ‘green’ objective is re-legitimising mining-led development. In Indonesia, such ‘green developmentalism’ builds on long standing ‘resource nationalism’ – the belief that Indonesia’s natural resources should be owned and controlled by Indonesians.

Nickel is an important ingredient in the lightweight, powerful lithium-ion batteries used in electric vehicles (EVs). According to the International Energy Agency, annual demand for nickel is expected to increase nineteen fold by 2040 from 2020 levels. Indonesia is the largest nickel producer and boasts the largest reserves in the world. The Indonesian government has increasingly promoted ‘down-streaming’ nickel mining and smelting to create more refined nickel, lithium-ion batteries and EV production as the best pathway to ‘net zero’ whilst promoting development. We call this the ‘EV-fix’ for the mining industry’s dilemmas.

In Indonesia, as globally, the political power and influence of fossil-fuel corporations have long been blamed for resisting the energy transition, while renewable energy advocates grapple with disjointed goals, policies and implementation by the state. However, with the ‘EV-fix’ such a dichotomy of competing interests is blurred. The global energy transition is prompting a reorganisation of extractive industries around electric vehicle production with renewed legitimacy.

A green development-resource nationalist nexus explains the ways that decarbonisation efforts are harnessed by politicians, state-owned enterprises (SOEs), mining conglomerates and foreign investors. Before outlining the specific strategies of each of these groups of actors, we first review a brief history of resource nationalism and the ‘down-streaming’ of nickel mining in Indonesia.

Resource nationalism

Resource nationalism has always been a feature of the Indonesian Republic. Article 33(3) of the 1945 Constitution states: ‘The earth, water and natural riches’ should be used by the state to maximise the prosperity of ‘the people.’ The current iteration of resource nationalism started with the mining law of 2009. Two measures were of particular importance:

- The requirement for foreign-owned mining companies to progressively divest up to 51 percent of mine ownership to domestic companies.

- A system of export bans, tariffs and quotas on unrefined minerals.

The measures were aimed at stimulating downstream processing of minerals (smelting and refining) and capturing value through government revenue, domestic linkages and employment. Most prominent until 2017 were restrictions on exporting unrefined nickel ore. Copper, tin, iron, lead, zinc and manganese ores also had to meet minimum concentrations prior to export.

Resource nationalism shifted mine ownership from foreign multinationals to domestic conglomerates. Between 2016 and 2020, Newmont, Newcrest, BHP and Rio Tinto all sold their major assets in the country to state and private domestic conglomerates. Freeport-McMoRan retained just under 49 percent of gigantic Grasberg mine in West Papua. These acquisitions helped domestic conglomerates evolve from local partners of multinationals to controlling managers of Indonesia’s largest mines.

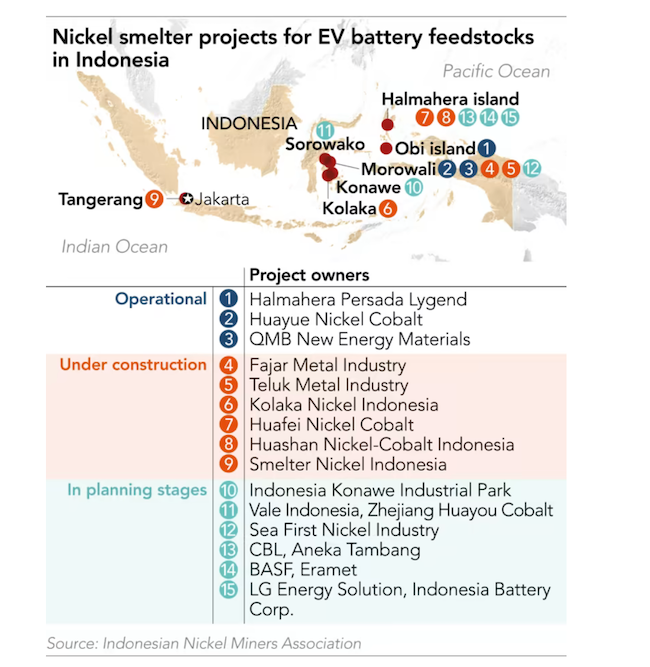

Resource nationalism also triggered a wave of investment in nickel-smelting by Chinese capital. From 2014 to 2023, over US$22 billion flowed into the construction of nickel smelters in Central Sulawesi’s Morowali alone. The number of nickel smelters has jumped from just 15 in 2018 to 62 as of early 2023, making the country one of the top producers of refined nickel products and stainless steel.

Despite the constitution specifically invoking ‘the people,’ the beneficiaries of resource nationalism have been politicians and mining conglomerates, while communities affected by mining and indigenous people suffer environmental and social impact. North Maluku’s Obi Island, which was mainly a fishing town with rich biodiversity until a huge nickel smelter was built there in 2015, is full of the toxic residues, destroying villagers’ livelihood.

Following the successful down-streaming of nickel production in Indonesia, global nickel demand fortuitously boomed for use in lithium-ion batteries.

Batteries

The cathodes of lithium-ion batteries require a mix of metals including cobalt, nickel, aluminium, and manganese. Nickel-rich batteries, with up to 50kg of the metal per EV, are ideal because they are energy-dense and relatively light weight. However, the nickel smelters constructed in Indonesia between 2014 and 2019 mostly produce nickel pig iron and ferronickel – important ingredients in steel production. Lithium-ion batteries require nickel sulphate or the precursor mixed hydroxide precipitate (MHP). To produce these, a new generation of energy-intensive high-pressure acid leaching (HPAL) smelters are under construction. To stimulate the construction of HPAL smelters, the government deployed the same resource-nationalist measures that initially attracted Chinese capital. From January 2020, the Ministry of Energy and Resources re-banned all exports of unrefined nickel. The environmental challenges of HPAL smelters add to existing concerns over labour standards, carbon emissions, land conflict and community resistance around nickel mining. Toxic tailings are disposed through controversial deep sea tailings placement.

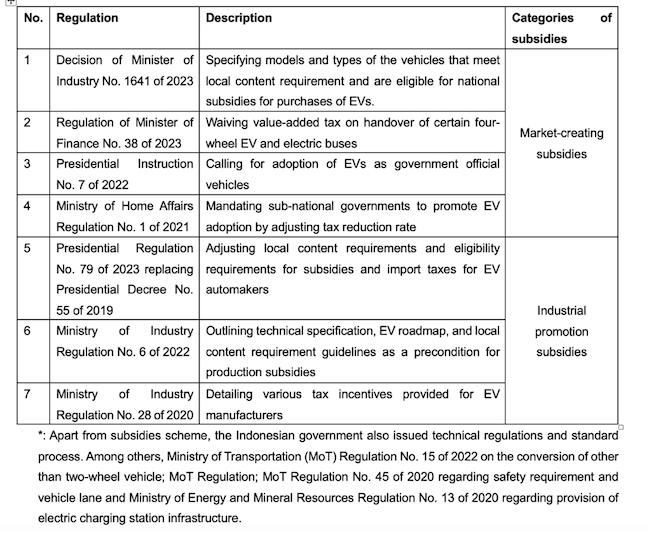

The resource nationalist-green developmentalist push is not limited to the construction of new smelters. It aims to build an entire production network, from mineral extraction and refining to battery assembly and EV construction. To incentivise this, the Indonesian government issued Presidential Decree No. 55 of 2019 on the acceleration of the program for EVs for road transportation. A further array of market-creating and industry-supporting regulations (Table 1 below) aim to facilitate the government’s ambition to have two million E-cars and 13 million electric motorbikes on the road by 2030.

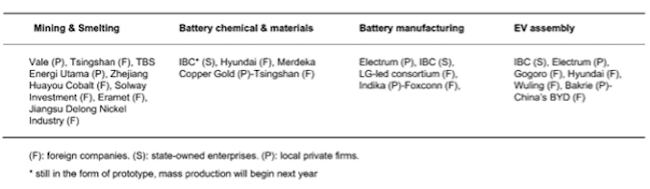

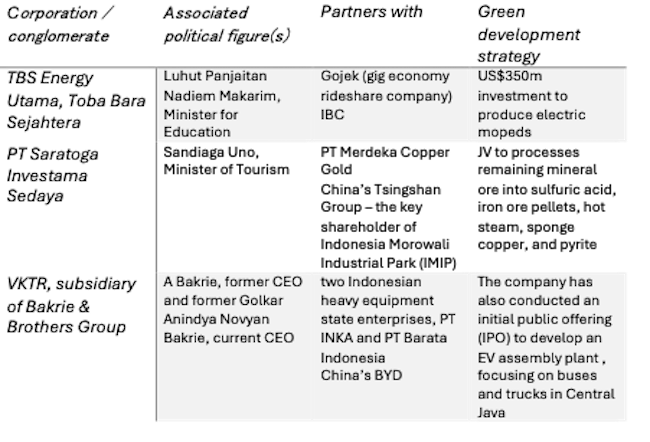

These measures, a combination of green developmental strategies, resource nationalism and the opportunities of a global boom, are facilitating the rise of an EV production network in Indonesia. Table 2 identifies the major corporations involved at each stage of production.

The Indonesia Battery Corporation

Four key groups shape and benefit from the green development-resource nationalist nexus:

- Major SOEs organised under the new Indonesia Battery Corporation (IBC).

- Old private mining conglomerates.

- Foreign newcomers including Korean and Chinese auto manufacturers and battery producers.

- Senior government politicians and officers, centred on the executive.

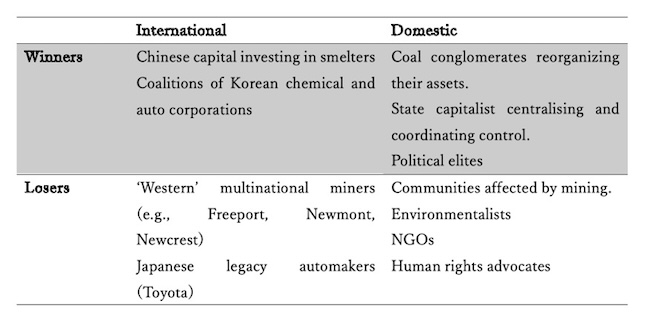

While the nexus facilitates a coalition of ‘winners,’ it also produces (temporary) ‘losers.’ Western multinational mining corporations lost when they were forced to sell assets at discount prices. Another major set of ‘losers’ are communities and environments affected by mining and processing nickel. Japanese automakers, reluctant to invest in EVs, are being left behind.

The shift to battery materials requires coordination. In 2021, four prominent SOEs - Mining and Industry Indonesia (MIND ID), PT Pertamina (petroleum giant), PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN, electricity infrastructure), and PT Aneka Tambang (assorted mining) – came together to create the Indonesia Battery Corporation (IBC). Mining and Industry Indonesia (MIND ID) is itself a creation of mergers between smaller SOEs in extracting and processing minerals. According to the Indonesian Minister for SOEs, Erick Thohir, the IBC will invest in nickel mines and smelters, controlling up to 51 percent, and 25-40 percent of precursor refineries and cathode plants.

Under the EV-fix, state capitalists coordinating production exploit national resources in the name of ‘the people’ while courting joint ventures with foreign capitalists who possess technology and expertise. As Luhut Pandjaitan, Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment, argued in a speech in Jakarta:

Many of you think that we are opening a wide door for China. That is not the case. We offered investment opportunities to everyone, even to Japanese companies, but they are still reluctant to invest in the EV sector. I will keep fighting to make downstreaming a success… I do this not for me, but for the entire country and the next generation to come.

While Chinese and Korean investors provide capital and expertise, the IBC secures their investment and controls risk. New entrants like Korean companies secure their investment with a priori knowledge that the Government will make the project work at all costs. In September 2021, the LG-led consortium (LG Chem, LG Energy Solution, LG International, POSCO, and China’s cobalt company, Huayou Holdings) and IBC launched the first EV battery factory in Southeast Asia, with an investment of US$1.1 billion.

Conglomerates

Many of the largest extractive conglomerates in Indonesia have aligned their interests within the green development-resource nationalist nexus. The nexus enables them to maintain relevance as local partners despite limited experience in the EV industry. Some of them have established links with smelters in Central Halmahera and Morowali, and access to nickel supplies.

For example, Indika Energy, one of Indonesia’s largest coal mining and power companies, sees EV-powered development – both upstream and downstream – as a new fix for its challenges. In 2021, it acquired gold mining company Nusantara Resources Limited (NRS), and metal ore trader Perkasa Investama Mineral, while reducing its investment in coal. In September 2022, Indika set up a joint venture with Foxconn to develop lithium iron phosphate batteries. This joint venture helps fix Indika’s over-reliance on coal, with fifty percent of its revenue set to come from non-coal interests by 2025. As CEO Azis Armand argued, ‘If we look only at the coal sector, our participation won’t be sustainable in energising Indonesia.’

Extractive conglomerates have changed strategy from challenging decarbonisation to embracing green development through low-carbon technologies under the coordination of SOEs and the political executive.

Politicians

At the apex of the nexus, the President and senior Ministers create incentives, local content requirements and subsidies to boost EV uptake. In addition to the market-creating and industry-supporting regulations listed in Table 1, the Jokowi Administration provides subsidies for EV manufacture. Effective from 20 March 2023, US$450 in tax deductions (about 7 million rupiah), will be provided for each new electric moped made in Indonesia. The government will subsidise purchases of up to 138 electric buses and 35,900 electric cars in 2023. Among cars, only Hyundai’s Ioniq 5 and China’s Wuling Air EV meet the requirement of at least forty percent local content. Among e-mopeds, there are at least twelve local brands that meet the threshold, including Gesits (IBC-owned), Volta, Yadea, and Selis.

However, to kick start new investment, Presidential Regulation No. 79 of 2023 relaxed local content requirement for automakers who are committed to producing at least forty percent of the content of EVs in Indonesia by 2026. Such automakers would be exempt from import tariffs and luxury taxes on imported EVs. At the time of writing, BYD is set to import three EV models directly from China. To benefit from the exemptions BYD committed to invest US$1.3 billion in a local manufacturing facility with a production capacity of 150,000 vehicles. Such targeted incentives de-risk pathways for international manufacturers to ramp-up domestic investment and production.

Another pivotal component of green developmentalism is the Presidents’ defence of resource nationalism. This was the case when the EU filed a WTO panel request in 2021 against restriction of nickel exports to European steel producers. The WTO ruled that the Indonesian Government violated the WTO provisions in Article XI.1 GATT 1994. President Jokowi vowed to challenge any WTO ruling against the ban on nickel ore exports and cover any fines while refusing to change the policy.

In short

In Indonesia, green developmentalism has built on long-standing ideologies and policies of resource nationalism to resolve some of the dilemmas of mining. The green development-resource nationalist nexus is a loose alliance of Chinese and Korean investors, domestic mining conglomerates, state-owned enterprises and the political executive who have found common interest in the nickel to EV production network. This EV-fix legitimises mining-led development and helps old conglomerates to reorganise their interests around green development. The biggest losers of the renewed mining led development are the local communities and activists resisting the impacts of mining on their land and livelihoods.

On 14 February, Prabowo Subianto, ex-army general and Defence Minister under President Joko Widodo, claimed victory in the 2024 Presidential Election and is poised to take office in October 2024. During the campaign, Prabowo repeatedly reiterated that he would continue (meneruskan) Jokowi’s key policies, including down-streaming of nickel and EV industries. Many voters sympathetic to Jokowi were drawn to Prabowo’s pledge of ‘continuity.’ All signs point to a continuation of the same policy agenda, with EV-fix remaining the social foundation of the green development-resource nationalist nexus.

Lian Sinclair (lian.sinclair@sydney.edu.au) is postdoctoral research associate in geography at the University of Sydney; Trissia Wijaya (twijaya@fc.ritsumei.ac.jp) is senior research fellow at Ritsumeikan University, Osaka. This article was drafted at a writing retreat generously organised by the Sydney Southeast Asia Centre. A longer version of this research is published in the journal Environmental Politics.