Why has the government failed to do more to adopt health policies consistent with the right to health?

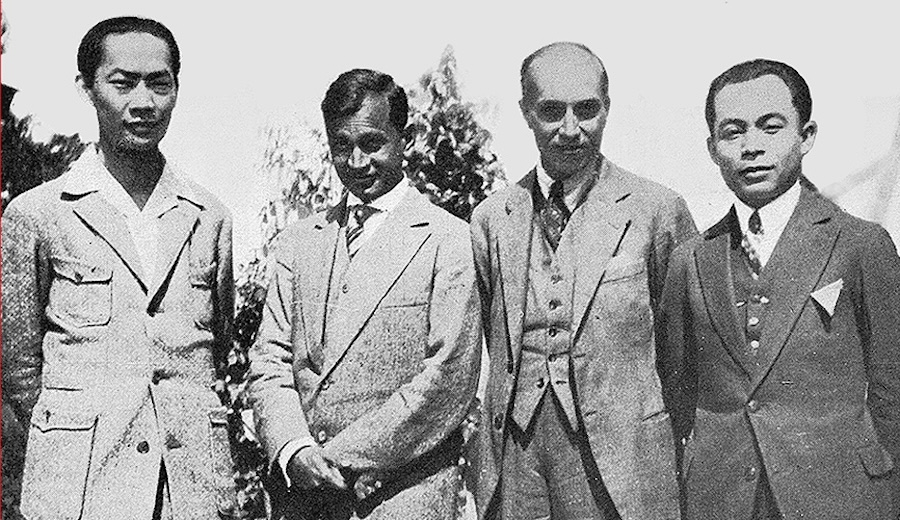

Andrew Rosser, Luky Djani, Wahyudi M Tohar, and Fahmy Badoh

The amendments made to Indonesia’s 1945 Constitution following the fall of Suharto’s New Order regime in 1998 saw the introduction of a range of provisions strengthening protection of the right to health. These included articles granting Indonesian citizens entitlements ‘to obtain health services’; ‘have a good and healthy living environment’; have access to social security and ‘develop oneself through the fulfilment of basic needs’. Subsequent laws and regulations have reinforced and expanded upon these entitlements.

In the wake of these amendments the extent to which Indonesia has adopted policies consistent with the right to health has varied significantly from one health policy issue to another.

On the positive side, in the past two decades the government has dramatically increased public health spending, ensuring more resources are available to support public health services and programs. It has also established a national health insurance scheme (JKN), a crucial step towards universal health coverage. Universal health coverage means that all people have affordable access to health care when they need it. It is consequently regarded as vital to realising the right to health.

On the negative side, the government has failed to introduce effective policies to improve the quality of the country’s health services, address the country’s growing burden of non-communicable diseases, enhance access to clean water and sanitation, control addictive and harmful substances and ensure healthy environmental conditions. It has also not yet introduced effective policies for controlling the spread of deadly infectious diseases, as persistently high tuberculosis and HIV/AIDs burdens and the country’s experience with COVID-19 illustrate.

This uneven policy record has translated into minimal improvement in the country’s scores in the Social and Economic Rights Fulfilment (SERF) Index, an instrument which measures countries’ progress in realising a range of social and economic rights in practice. In 2007, Indonesia’s SERF score for the right to health was 83, indicating that the country achieved only 83 per cent of what was possible in fulfilling this right given its level of per capita income. By 2018, the latest year for which SERF scores are available, its score had increased only slightly to 84 per cent.

Why has the Indonesian government failed to do more to adopt health policies consistent with the right to health? What have been the main obstacles to change?

Deficient leadership

Part of the answer is deficient leadership at the Ministry of Health. Over the past two decades, Indonesia has had several capable, well-qualified and well-regarded Health Ministers who have expressed strong commitment to the right to health and endeavoured to change policy to fulfil it.

But it has also had some Ministers whose commitment to the right to health, and actions in relation to it, have been questionable. Moreover, these individuals have been in office at key moments in time.

A case in point is Dr. Siti Fadilah Supari, who was Health Minister between 2004 and 2009, a period during which post-New Order democratic reforms were being consolidated and opportunities for rights-oriented policy change were consequently at a high point.

During her tenure as Health Minister, Supari championed national health insurance schemes that were important precursors to the JKN, oversaw the introduction of a new health law which imposed a requirement on government to spend at least five per cent of its budget on health, and stymied moves on the part of the Jakarta city government to corporatise local public hospitals, which would have threatened access to these hospitals for the city’s poor.

At the same time, as Minister, Supari made stinging criticisms of the World Health Organisation (WHO) and other foreign donors active in Indonesia’s health sector. At one point she accused the former of being involved in a conspiracy related to the use of Indonesian bird flu virus strains. Such criticism poisoned relations with foreign partners, leading to reduced international health collaboration and more limited scope for new initiatives to promote the right to health.

Supari also undermined good governance in the health sector by abusing her position for personal gain. In 2017, she was convicted on corruption charges related to the procurement of medical equipment that occurred during her term as Minister and sentenced to four years in gaol.

Dr. Terawan Agus Putranto was Health Minister from October 2019 to December 2020, during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic. Prior to becoming Minister, Terawan had been suspended by the Indonesian Medical Association (IDI) for promoting a controversial treatment for stroke, colloquially known as ‘brainwashing’. There is little evidence that this treatment is effective and some evidence that it could cause harm.

Once he became Minister, he caused further consternation by declaring - just before the first cases of COVID-19 were reported in Indonesia – that Indonesians would be protected from the virus because they are religious people who believe in the power of prayer. He later downplayed the threat posed by COVID-19, stating that the disease was ‘self-limited’ and patients would ‘heal themselves’.

In late 2020, amidst criticism of his handling of the pandemic, he was removed from his position as Health Minister. Since then he has continued to court controversy by promoting a COVID vaccine known as Vaksin Nusantara. In spruiking this vaccine, he has received endorsements from key members of the political and military elite who have been his patients. But like ‘brainwashing’, there is little credible evidence to support his claims as to its effectiveness. In March 2022, IDI eventually decided that enough was enough, and expelled him from the organisation.

Structural obstacles to change

The scope for the government to adopt policies that are consistent with the right to health has also been constrained, and arguably more fundamentally constrained, by structural factors. That is, ones related to the broad configuration of power and interest in the country.

As much analysis of Indonesian politics over the past two decades has shown, oligarchic elites nurtured under the New Order have continued to dominate Indonesian politics. These elites have included senior military figures, leading business people, senior bureaucrats and politicians from the major political parties.

Such elites have had little interest in promoting improved social welfare and, in particular, the right to health in Indonesia. Instead, their principal interests are capturing the state apparatus and, with that, access to the rent-seeking opportunities afforded by control over the allocation of state licences, concessions, credit, employment opportunities and other facilities. They have also had a strong interest in maintaining and advancing the corporate empires that their members have built or to which they are closely linked through cronyistic networks.

In this context, there has been significant resistance to government adoption of policies consistent with the right to health where it has threatened the interests of the oligarchic elite.

Resisting reform

Perhaps the clearest example of this activity relates to tobacco control. Smoking rates in Indonesia are amongst the highest in the world, particularly among men, contributing to an estimated 225,700 tobacco-related deaths each year. Post-New Order governments have consistently failed to enact strong tobacco control measures, undermining efforts to promote the right to health.

Whilst they have introduced some requirements for cigarette packets to include both pictorial and harsher written warnings they have continued to permit widespread tobacco advertising, backtracked on nicotine and tar limits, kept tobacco excise rates low, continued to promote increased domestic tobacco production and refused to sign the key international standard on tobacco control, the WHO’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC).

Many of the country’s major tobacco companies are, or in the recent past have been, owned by local business families with strong political connections. Government unwillingness to adopt a stronger position on tobacco control has reflected the fact that the tobacco industry has actively resisted the introduction of new tobacco control measures. It also reflects the political and economic power of these companies.

Tobacco companies are major employers, provide substantial state revenues in the form of tobacco excise payments, are politically organised, and fund a range of education, cultural, musical and sporting events. They are also widely regarded to be a key source of election campaign finance and patronage resources for politicians and political parties, giving them privileged access and ensuring they are deeply integrated with the oligarchic elite.

Another example of oligarchic resistance to government adoption of policies consistent with the right to health relates to the JKN. The creation of the JKN (and accompanying social security reforms related to labour protection) meant increased costs for business due to mandatory social security charges. The transfer of control over social security funds from the traditional social security state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as PT Askes and PT Jamsostek was also handed over to two new agencies, BPJS Kesehatan (BPJS Health) and BPJS Ketenagakerjaan (BPJS Labour). This was important because these SOEs were a source of funding for strategic government initiatives and rents for government officials, well-connected business groups and senior officials. This decision led to a series of protests from the business community against cuts to fuel subsidies and the implementing legislation for the JKN.

In contrast to the tobacco lobby, such oligarchic resistance proved ineffective in this case. Importantly, the new health insurance programs attracted support from popular elements, particularly sections of the trade union movement, resulting in massive demonstrations in favour of the scheme. These demonstrations caused significant disruption and served to even the ledger politically, with the legislation eventually adopted. The cause of change was also assisted by the fact that numerous political leaders, particularly at the local level, had championed pro-poor health insurance reforms as part of their successful election strategies.

Looking forward

During the initial stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia, it appeared that it might precipitate a significant realignment in the balance of power between oligarchic forces and more progressive and technocratic forces in Indonesia. Almost three years into the pandemic, however, there is little sign that it has had this effect. Indeed, the Indonesian government’s response to COVID-19 has been accompanied by moves to sideline progressive and technocratic elements by seeking to silence criticism of President Joko Widodo and, in particular, his government’s handling of the pandemic. In this context, the future of the right to health in Indonesia will depend to a large extent on what its populist political leaders find electorally advantageous to promote rights-oriented health reforms in the future, and such reforms generate new popular mobilisations of support.

Andrew Rosser is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at the University of Melbourne. Luky Djani is Lecturer in Political Science at Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jakarta and a researcher at the Institute for Strategic Initiatives. Wahyudi Tohar is Director of the Institute for Strategic Initiatives. Fahmy Badoh is a social activist and former program manager at Transparency International Indonesia.