Urban poor people’s rejection of all candidates in the 2024 Jakarta gubernatorial election shows their capacity to self-organise for their interests

Amalinda Savirani

On 27 November 2024, 37 provinces and 508 regencies/cities in Indonesia simultaneously held regional head elections. During the election campaigns, many of the candidates used populist slogans to enhance their ‘pro-people’ credentials. Yet, none of the candidates presented a strategic vision and mission to tackle issues that concern the common people, especially the urban poor. This neglect of the urban poor’s interests was also evident in the Jakarta gubernatorial elections.

In sidestepping the urban poor, the regional head candidates underestimated this group’s capacity to organise for their own interests. In Jakarta, this was clearly demonstrated in a unique grassroots movement organised by the Urban Poor People’s Network or JRMK (Jaringan Rakyat Miskin Kota), urging constituents to vote for all candidates on the ballot thus rendering their vote invalid. The movement marked a significant turning point in urban poor politics, moving away from JRMK’s previous strategy of signing political contracts with electoral candidates.

Political contracts

Since 2012, JRMK utilised the gubernatorial elections in Jakarta to promote programs that have been neglected by Jakarta’s leaders. As a movement that focuses on fighting for the rights of the poor, JRMK tried to convince gubernatorial candidates to put the urban poor’s interests on their political agenda. They did so by negotiating political contracts with the candidates, in which they pledge to mobilise the urban poor into voting for a candidate in exchange for the candidate fulfilling the JRMK’s demands stated in the contract, if elected.

During the 2012 Jakarta elections, JRMK signed political contracts with both candidates running for governor and vice-governor: Joko ‘Jokowi’ Widodo, with running mate Basuki ‘Ahok’ Tjahaja Purnama, and Anies Baswedan, with running mate Sandiaga Uno. In the political contract with Jokowi, the former Mayor of Solo signed JRMK’s demands with the title, ‘Pro-Poor Citizens, Based on Service and Citizen Participation’. It stated that they would implement housing security and provide basic services such as free education and health care. Once they were elected, Jokowi–Ahok initially appeared to follow through with JRMK’s wishes on basic services, but not for housing security. This lack of commitment to housing security became clear when Ahok became governor after Jokowi won the presidential election in 2014. Ahok’s governorship in 2015–2016 was marked by polarising polemics as well as mass evictions of slum areas, thus antagonising the urban poor. Records from the Legal Aid Foundation Jakarta (LBH) show that more than 25,000 people were evicted in this period.

During the 2017 Jakarta election, JRMK sided with Ahok’s rival, Anies Baswedan, and ensured that the political contract it signed with him contained a guarantee that there would be no more evictions. After Anies won the gubernatorial election, as a result of this political contract the housing rights of evicted residents were restored. Although their previous settlements were considered ‘illegal’ due to the absence of land certificates – while the residents still paid land and building taxes – Anies arranged for their legal settlement in new public housing complexes built in North Jakarta, the residential villages Akuarium and Kunir. Moreover, different from the top-down implementation of previous public housing projects, the residents were consulted in the design of these housing complexes.

Following this successful outcome and JRMK’s previous positive experience with Jokowi, a political contract was again presented to Jokowi when he ran for president in the 2014 and 2019 elections. The results of these political contracts were far from the urban poor’s expectations. Throughout his presidency, Jokowi prioritised large infrastructural projects that not only neglected the common people’s interests, but often led to their eviction. This left urban poor organisations like JRMK heavily disappointed, and rethinking their strategy of bargaining with political elites.

From no vote to vote 'all'

In the Jakarta gubernatorial election on 27 November 2024, no political contract was presented to the candidates. The last time JRMK signed a political contract was during the presidential election on 14 February 2024, with then presidential candidate Anies Baswedan. However, Anies was blocked from competing in the Jakarta election in November by the national KIM coalition – or the Advanced Indonesia Coalition that encompasses almost all political parties (minus PDI-P), supported by former president Jokowi and incumbent president Prabowo Subianto. Candidates running for the Jakarta office included the KIM coalition’s candidate Ridwan Kamil, the PDI-P’s candidate Pranomo Anung, and the independent Dharma Pongrekun. JRMK did not consider any of these candidates to be aligned with residents’ housing rights or other urban poor issues. For them, the worst option was Ridwan Kamil, who in 2019 as then mayor of Bandung, ordered the eviction of four urban villages in the city’s Tamansari area for the construction of modern row houses.

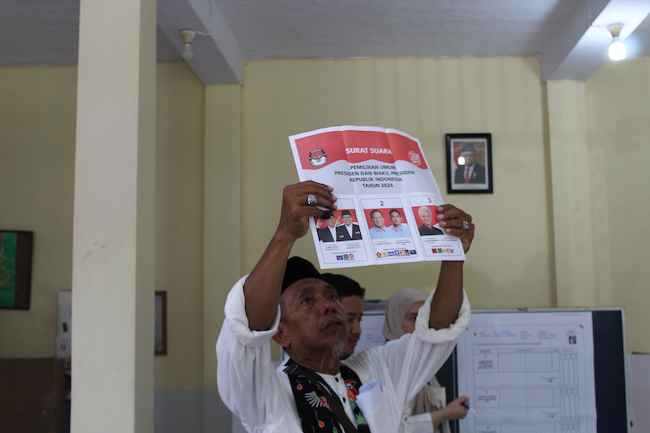

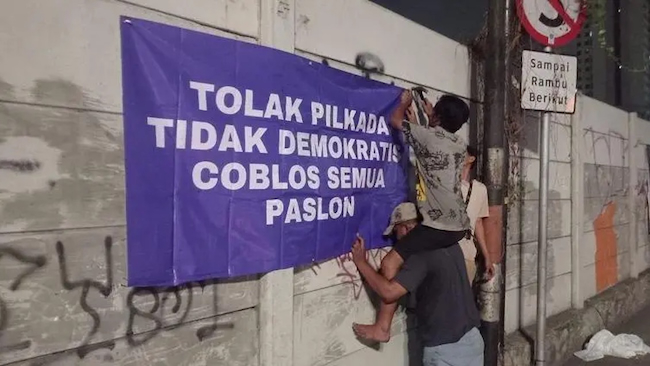

Losing hope in a favourable election outcome for urban poor residents, JRMK launched the Gercos campaign – an acronym for ‘vote for all movement’ (Gerakan Coblos Semua) – as a form of resistance to the lack of support from the gubernatorial candidates for urban poor issues in this regional political contest. It invited residents in the Greater Jakarta region who have the right to vote to still come to the polling station but not to cast their vote for one candidate, and instead to vote for all candidates on the ballot, resulting in the ballot paper being invalid.

The Gercos campaign represented a form of ‘golput’, an acronym for ‘white group’ (golongan putih) or no-vote movement, which led some politicians to label it as an election violation. As stated in Article 284 of the Election Law, it is prohibited to persuade others not to use their right to vote, but with the added provision ‘by offering money or other material rewards’. JRMK did not offer any reward in persuading residents to join the Gercos initiative, therefore no legal action could be taken against it. Still, it received a strong backlash from politicians and their supporters on social media for allegedly undermining the democratic process.

But some observers noted that Gercos was a democratic response to the political elite’s neglect of the people’s interests. Indeed, the Gercos campaign rejected the dominant power of the KIM coalition and the elite-centric nature of the Jakarta elections, which was not without risks. By its overt rejection of all candidates it risked alienating the political elite and closing off the opportunity for negotiation. The biggest risk was that basic housing rights would disappear from the political agenda altogether.

Risky choices

For the urban poor residents represented by JRMK – many of whose members also worked as street vendors or had been victims of eviction – there was much at stake. If they wanted to be pragmatic, they could have supported the candidate with the highest electability and potentially been able to negotiate a deal with this candidate. As they saw it, this would make them no different from political parties whose pragmatic agendas made them likely to sell out on the values and principles of democracy. The choice not to go along with the political elites was not only an idealist one. It was also strategic. By now JRMK understood that pragmatic choices are also vulnerable to failure.

Indonesian electoral politics is expensive. The three candidates in the Jakarta gubernatorial election each spent billions of rupiah on their campaigns. The question is, where did these funds come from? In an urban context, especially for Jakarta, the most important policy is spatial planning management, including property development. The property industry and other urban developers are the main actors affected by the results of the gubernatorial election. Studies show that property developers were key actors in Jakarta’s land use policies and city planning in general, and that they have been able to commit many violations related to land use, with the blessing of the state. This means that the majority of campaign funding could come from this group.

The interests of urban developers and the Jakarta government coalesce in their prioritising of the urban elite as well as middle class. In the context of housing provision, both stand to gain from developing middle-class housing in the city centre, so that middle-class office workers can live closer to their workplace instead of spending at least three hours a day commuting. In this context, the right to housing for the urban poor to live in the city is far less of a priority, regardless of which candidate is elected Jakarta’s governor.

This is the lesson JRMK learned from the 2017 gubernatorial election in Jakarta. Political contracts signed before the election could not offset the prioritisation of elite and middle-class oriented spatial planning after the election. For the 2024 Jakarta election, the organisation realised that any of the candidates they could support would also be supported by powerful developers that do not have the people’s interests in mind.

So it was that the urban poor in Jakarta faced multiple risks and dilemmas in the 2024 gubernatorial election. Launching the Gercos campaign meant forsaking their bargaining position in trying to secure basic housing rights and prevent further evictions of the poor by the new governor. But the organisation deemed it to be the more strategic choice compared to bargaining in vain with a future governor whose interests already aligned with the property industry. What, then, could the urban poor hope to gain with the Gercos campaign?

Maintaining hope

JRMK received much criticism for the Gercos campaign, and not only from politicians. Political observers and even members of civil society groups belittled the initiative as being in vain, and a waste of time. This is reminiscent of the criticism launched at a similar initiative taken by a group of activists in the run-up to the 2024 presidential election in February, called the ‘4 Finger Salute’ campaign. This campaign called on voters to choose candidates number 1 or number 3 on the ballot – that is, Anies Baswedan and his running mate Muhaimin Iskandar for number 1, or Ganjar Pranomo and his running mate Mahfud MD for number 3, which together amounted to the number 4 – in order to block a one-round electoral victory for candidate number 2, Prabowo and his running mate Gibran Rakabuming Raka. While the 4 Finger Salute campaign proved to have little effect on the election outcome, it did signal a new resistance to candidates who represent the interests of the elite.

Likewise, the Gercos movement is an affirmation that the people – including the urban poor –have an important role in a democracy, and they cannot be suppressed, fooled, and ignored. During the 2024 legislative election, which coincided with the presidential election, this conviction led many JRMK members to run as legislative candidates for the Labour Party, one of the few political parties not controlled by the oligarchy. Although the Labour Party failed to win any seats in parliament, it demonstrated that elections are not just for the rich.

After many years of political bargaining that sustained their dependency on the political elite, the Gercos movement represents a new political strategy for the urban poor. It demonstrates their conviction that the elite-centric politics in the Jakarta gubernatorial election needs to change. As a form of protest against political elites that underestimate urban poor residents, and a symbol of citizens’ resistance to the increasingly monochromatic political climate in Indonesia’s electoral democracy the Gercos movement represents a fresh alternative.

It maintains the hope of civil society movements that true democracy is possible and worth fighting for. It also shows that such hope is not some romantic ideal, but a strategic choice to thwart the cycle of injustice, which requires systematic organisation, acceptance of failure and long-term endurance. By opting for Gercos, the urban poor demonstrate that they have this endurance.

Amalinda Savirani (savirani@ugm.ac.id) is a Professor at the Department of Politics and Government, Universitas Gadjah Mada, Yogyakarta. An earlier version of this article was published in Indonesian in Project Multatuli.