An anonymous Javanese text written in response to the flu epidemic of 1918-19, offers its audiences eerily familiar lessons for surviving a pandemic

Nancy K. Florida

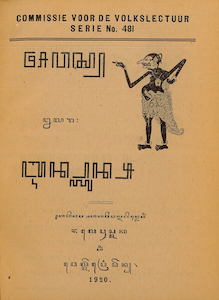

In response to the devastating flu epidemic of 1918-19, the government publishing house Bale Pustaka issued a slim volume of some 52 pages in Javanese language and script, illustrated with figures from the wayang (shadow puppet theatre) tradition. The volume, titled Awas Lĕlara Inpluwensa (Beware the Disease of Influenza), was to be distributed among the Javanese populace as a public health measure.

Beware the Disease of Influenza tells a story of the epidemic in Java, while at the same time offering measures to control the outbreak and to treat its sufferers. Though it was not written in the form of a wayang shadow play, the story is told in the idiom of wayang and the form of a play. Below you will find a complete translation of this short pocketbook.

A public health intervention

Commissioned by the Health Service of the Netherlands East Indies government in May 1919, the book came out the following year. By then it was too late, several millions had already perished and the epidemic was on the wane. It is estimated that in the space of a year the flu had caused a population decline of between 4.26 and 4.37 million in Java and Madura (excluding the Principalities) – with most of the deaths occurring in late 1918. This was approximately ten per cent of the population of these most populous areas of the colony.

We do not know who the author of the book was, but we can surmise that he (or possibly she) was a Javanese who was well-versed in the wayang and in Javanese literary conventions. The author may well have been a dhalang (shadow puppeteer). He or she was also well-informed on the most recent advances in modern medical knowledge pertaining to the causes and treatment of influenza. The book forms an epistemological translation of sorts, across these different worlds of knowledge. Traditional wayang characters, living in a traditional wayang world, encounter and meet the challenges of a contemporary early twentieth-century medical emergency.

The story

The light-hearted story that our author tells in the form of a play revolves around the figures of the punakawan, that is, the retainers that serve the noble heroes who are the protagonists of the wayang stories. The punakawan, who appear and reappear in every wayang play, perform both as clowns and as voices for the ‘little people.’ Sĕmar is the most senior of the punakawan we meet in Beware the Disease of Influenza. With his obese form and weepy eyes, Sěmar is the father of the two other punakawan who appear as protaganists of the story. Though he is a lowly servant, Sĕmar is in fact the highest of the manifest gods. He is noted for his wisdom and supernatural powers and is often considered the guardian spirit of Java. Sĕmar’s divine name is Bathara Ismaya; he is the second egg-born son of the highest god, Sanghyang Wĕnang (the Almighty), having been created from the white of the divine egg.

Sĕmar’s sons are Petruk and Gareng. Petruk, the younger son, is the ‘hero’ of our story. Tall and thin, with a pointy nose and little pot belly, Petruk is the brash one and it is he who leads the effort to eradicate the flu. Gareng, the elder son, is short and plump. He is riddled with tropical yaws, a disease of poverty. A bit whiny and ‘school-marmy,’ Gareng joins with his brother and father in the effort to combat the epidemic. The three are portrayed as ordinary, if enterprising, Javanese villagers.

The other punakawan to appear in the story is Togog. Short and obese, with a hideously deformed wide mouth, the Togog of the wayang world serves as a retainer to the forces of evil (demons or foreign enemy kings). But he is also Sĕmar’s brother. The eldest son of Sanghyang Wĕnang, Togog was born of the shell of the divine egg. In our story he appears as the head of a village that has been struck down with influenza – and as the father of the lovely Sari-hati (Heart’s Essence).

The other central figure in the story is ‘the most noble Sir Doctor’ (Bĕndara Dokter), a Javanese doctor. An unparalleled master of modern medical science, Bĕndara Dokter is a clever aristocrat, depicted by the wayang figure of Krĕsna. In the wayang world, Lord Krĕsna is the world-conquering hero who is an incarnation of the god Wisnu. He wields his power, in part, through the means of his supernatural weapon, a blazing discus, or chakra. In our story, the chakra is the receptacle of all the doctor’s modern medical knowledge. He bestows this magical, world-conquering weapon upon Petruk, thereby instantly endowing the Javanese ‘little man’ with the means and methods of modern scientific medical knowledge.

At the close of this very short book, Petruk conveys this ‘magical-modern’ knowledge to his new bride Sari-hati and to the villagers whom he has just cured – while at the same time, by extension, delivering it to the most important audience, the Javanese readers of the book. The final section of Beware the Disease of Influenza comprises a short treatise on the etiology and epidemiology of influenza as it was understood at the time, as well as a textual guide on both the treatment of the disease and the prevention of its spread.

The song

The ‘treatise’ is composed as a song in traditional Javanese verse (macapat) in Sinom verse form, a melodic form considered appropriate for delivering teachings. Macapat verse is written to be sung, and one can presume that at least some of the Javanese readers would have sung this final section of the book – reading it aloud to themselves or to their fellows in the easy, steady cadences of Sinom.

In the Javanese script published edition, the text of these teachings is presented in hybrid form – the first stanza is graphically presented in poetic form, while the following stanzas are graphically rendered in numbered paragraphs (2-15), as if they were prose. And yet, as Petruk notes, the entire text conforms to the metrical rules of Sinom meter, and thus may be (or is meant to be) sung. It is for this reason that, as you will see below, I have made the choice to render all thirteen stanzas graphically in poetic form, while retaining the numbers that indicate the numbered paragraphs, each of which constitutes a separate topic.

I invite readers to imagine Petruk, the clown and emblematic ‘little man’, reciting these teachings to his fellow Javanese in an engaging melodic voice – and doing so in a very traditional form according to the strict prosodic rules of sung Javanese poetry – thereby to instill in them a more ‘modern’ consciousness of the disease that was threatening them and very well might return to threaten them again.

The Text

Key references

Lelara Influenza = Awas Lĕlara Inpluwensa.1920. Weltevreden: Bale Pustaka.

Chandra, Siddharth. 2013. ‘Mortality from the Influenza Pandemic of 1918-19 in Indonesia,’ Population Studies, Vol. 67, No 2: 185-93.

Ravando. 2020. Perang Melawan Influenza: Pandemi Flu Spanyol di Indonesia Masa Kolonial, 1918-1919. Jakarta: Kompas.

Nancy K. Florida (nflorida@umich.edu) is Professor Emerita of Indonesian and Javanese Studies at the University of Michigan.