Some Dutch museums are taking more critical approaches to colonial history

Susie Protschky

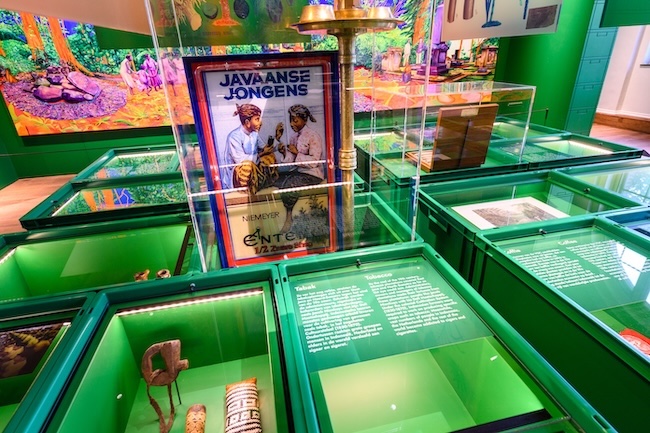

In 2023 Amsterdam’s Tropenmuseum was renamed the ‘Wereldmuseum Amsterdam’. Its partner museums in Leiden and Rotterdam have also been rebranded ‘World Museums’. The name change is the latest in a long history of reinventions by three institutions with colonial origins collecting from and researching in Indonesia, the Caribbean and Suriname. Recently, the World Museums have been at the forefront of more critical approaches to the Netherlands’ colonial past, including the restitution of looted objects to Indonesia. Beginning in 2023, these include hundreds of items known as the ‘Lombok treasure’ taken during the Dutch military conquest of Lombok in 1894, and a keris (dagger) taken during the violent subjugation of Klungkung (Bali) in 1908, among others.

Reckoning with ‘our colonial inheritance’

Last year was also the premiére of the Wereldmuseum Amsterdam’s new semi-permanent exhibition, ‘Our Colonial Inheritance’. The first time I went to see it, I had no company except for a group of local primary school-aged children in a summer camp. They made up a cross-section of multi-ethnic Amsterdam, from a variety of Asian, Afro-Caribbean and European backgrounds. I joined them in the antechamber to watch Bibi Fadlalla’s film Prologue to a Nation, playing across two big screens.

The film, which frames the whole exhibition, shows visibly diverse peoples symbolising the postcolonial communities of the Netherlands planting the flags of their various nations of origin in a quintessentially Dutch dunescape. We see Dutch officials addressing the state’s responsibility for colonialism. The Mayor of Amsterdam, Femke Halsema, acknowledges the city’s historic role in slavery (2021). King Willem Alexander apologises to Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo for Dutch forces’ ‘extreme violence’ during Indonesia’s National Revolution (1945–49) (2020). Former Premier Mark Rutte adds his apology for the same (2022). Then, a woman of colour asks ordinary people on Amsterdam’s streets, ‘what does our colonial heritage mean to you’? A young Indo-European woman speaks of her quest for identity among a community displaced several generations ago from their homeland. Two middle-aged white men say that once the empire signified pride, and now it’s a matter of shame. A young Indo-Ghanaian opens up about his early consciousness of being a ‘mixed’ kid in the Netherlands.

I watched the children watching the film. As they peeled off, one by one, to enter the rest of the exhibition, I wondered, did they see themselves in this film just now? How did they ‘see’ other people’s perspectives, and how will they, as they grow, answer that question, what does ‘our colonial heritage’ mean to you?

Over multiple visits since then, the exhibition has made me think about growing up in Australia, a country where colonialism is not in the past but in the present. It has had me reflecting on how history-making has changed over my twenty years of teaching and researching colonialism in Indonesia. I can’t help contemplating how colonial history is viewed today in the Netherlands, a country grappling with its past as a violent coloniser, among diverse people whose community origins, grievances and pride are entangled in this story of global slavery and imperialism. Perhaps particularly so since the 2023 Dutch national election, which saw the largest vote go to the far-right Geert Wilders, who wants to retract official Dutch apologies for slavery and colonial violence.

The exhibition’s provocative aim is to confront visitors with their own position on belonging, community, identity and the shared burdens as well as inspirations of the past. The curators weave Indonesia into a complex story of Dutch colonialism stretching across time and space, from the early seventeenth to the late twentieth centuries, and from West and South Africa to Japan, Taiwan, India, Australia, Suriname, the Caribbean and the Netherlands. The exhibition asks visitors to ponder ‘what is your position in these connected times and places?’ It deploys objects, images, narratives and questions that explicitly demand reflection, recognition, and even change from the viewer with respect to perspectives they might take for granted.

Decolonial memory work

‘Our Colonial Inheritance’ is a consciously didactic exercise in decolonial memory-work, one might even say memory activism. Certainly, that is how its critics will frame it and object to it: as a ‘woke’ exercise in foregrounding a divided past and present. Some visitors won’t like the museum’s emphasis on the contentious, oppressive and unjust aspects of a modern world built on empires, rather than lauding the glorious progress of nations like Indonesia and the Netherlands. Others may find themselves challenged to extend their personal perspectives and, perhaps, their political attention, through seeing new connections between Indonesia and other parts of the former Dutch empire in ways that offer alternate forms of solidarity based on local as well as global historical consciousness.

For example, the exhibition suggests how land-grabbing and ecological collapse in present-day Indonesia has its origins in colonial-era plantation agriculture and mining, both locally and further afield, in the networks binding the Netherlands, Antilles and Suriname. It shows how slavery, and the coerced movement of people was even ‘bigger’ in Asia, numerically, than the Atlantic. Forms of unfree labour not only flourished in both regions after slavery’s abolition, but remain foundational to the present-day economic development of Indonesia, the Netherlands and the world as a whole.

The exhibition acknowledges the enormous creative energy and almost incomprehensible human cost of resistance to colonialism. It also challenges simple chronologies of decolonisation. In the section on Indonesian independence, for instance, the visual narrative ends not in 1949, but with a photograph of a 1962 demonstration in Manokwari (West Papua) about the transfer of sovereignty from Dutch New Guinea to Indonesia. The image provokes reflections on the drawn-out end to Dutch rule and the rise of new dynamics of colonisation and resistance that have plagued the Republic of Indonesia since its inception.

Structured chronologically and thematically, ‘Our Colonial Inheritance’ passes through big topics that single out strands in Indonesian history. It constantly re-weaves these strands into the global fabric of colonial trade, slavery and unfree labour, environmental exploitation, racism, subjugation and resistance, war, independence movements, refugees and post-war migration, identity and culture, and remembering, celebrating and commemorating heritage.

The exhibition constantly pairs past with present perspectives and twins the recurring experiences of exploitation and oppression with resistance and resilience. It combines the museum’s material collections, which were once foundational to Dutch colonial trade, science and culture, with two other elements. First, is the explicit invitation to viewers to reflect on their own position on the past and their present notions of community. Second, is the work of contemporary artists reflecting on colonialism. The latter approach yields some wonderful insights. For example, the shared legend of royal ancestors among Indo-Europeans and Afro-Caribbean/Surinamese in the Netherlands. Artist Thania Petersen’s spectacular series of self-portraits, ‘I Am Royal’, give form to the fantasies of agency and grace that obscure unease about the patriarchal, racialised dynamics that shaped European men’s intimate relationships with local women, and thus the limited agency of the nyai (concubine) in colonial Indonesia.

‘Our Colonial Inheritance’ reclaims as relics of violence objects, images and historic figures that were once seen as neutral, or as symbols of Dutch imperial glory. Dutch armour and weapons from the era of Jan Pieterszoon Coen’s conquest of Banda are glossed as remnants of the genocide that drove survivors to the Kei islands, where descendants of this atrocity remain today. A seemingly innocuous portrait of the deposed Raja of Lombok, Anak Agung Gede Ngurah Karangasem, whom the Dutch exiled to Batavia with his household, is revealed to be a trophy photograph symbolising his subjugation. Objects looted from the Dutch pillage of royal palaces are signalled as being on the list for future repatriation to Indonesia.

Blind spots

Sometimes, the exhibition caters overmuch for a local audience. Dutch-language wall text quoting activists and politicians excludes foreign visitors. There is a tension in the exhibition between acknowledging slavery in Asia, and Atlantic slavery being given a distinct space. While the show clearly represents the hybrid cultures emerging from Javanese indentured labourers transported to Suriname, it neglects communities with descendants in contemporary Indonesia (Javanese and Chinese in Sumatra, for example) born from the same circumstances. Indonesia is not given the same sensitivity and depth of knowledge as are objects and images narrating the movement of people through trade and unfree labour networks in Suriname and the Caribbean.

The exhibition also elides or simplifies how colonialism co-opted existing Indonesian elites or new actors into governing and trade structures, and glosses over the pressing incentives for local communities to participate in land-clearing or the trade in human flesh. At the same, the show’s detail is frequently overwhelming. The cacophony of objects, overly didactive wall texts, films, screens, and audio accessible through QR codes create sensory overload. Given the content, which frequently evokes, describes or shows violence and suffering, getting to the final room is intellectually and emotionally exhausting. But maybe that’s a good thing.

The futures that colonised people fought and died for were fraught with uncertainty and conflict. The communities rebuilt after transportation, displacement and war were the work of many hands and minds. Perhaps that is also how the fullness of that past should also be represented.

Susie Protschky (s.protschky@vu.nl) is Professor of Global Political History at Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.