The njai and the babu have been iconic figures of nostalgia in Dutch cultural memory but a recently published novel challenges such remembrance

Pamela Pattynama

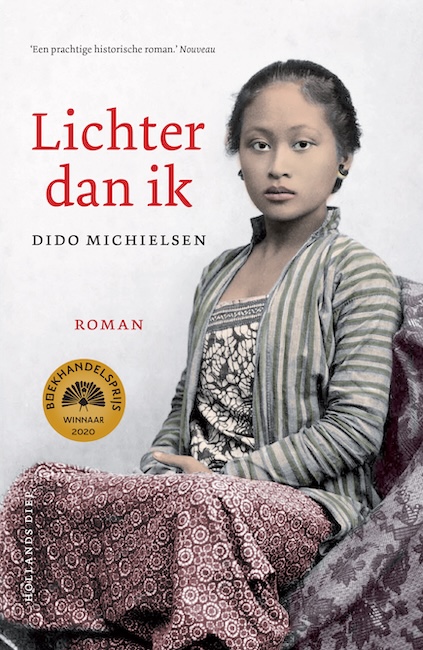

Dido Michielsen’s remarkable novel, Lichter dan Ik (Lighter than Me, translated into Indonesian as Lebih putih Dariku) was first published in 2019. It tells the fictional story of an Indonesian woman, Isah, who grows up in Yogyakarta's royal court, and chooses to become the njai (housekeeper/concubine) of a Dutch military man with whom she ends up having two daughters. Her hope is that they will get married, however the soldier returns to the Netherlands to marry a white woman, leaving Isah and his two daughters behind and uncared for. As a single mother with no income, Isah is forced to accept the conditions of an Indo-European family who want to adopt her two girls. She becomes the babu (nanny) to her own children, who never discover that Isah is in fact their biological mother.

Lighter than Me is part of a recent group of postcolonial interventions in the form of oral and visual cultural productions, which though each different in terms of their topics and form, have a significant element in common. In one way or another they articulate a radically critical view on the idea of the Dutch colonial past as an exotic, nostalgic and harmonious time or place; an idea that has been fixed in Dutch collective memory for centuries.

Postcolonial nostalgia and the njai/babu

Indonesia was the Netherlands’ most profitable, precious and longstanding colony, and until today a tradition of memory stories and nostalgic images about the Dutch East Indies pervades the collective memory of the country. Indonesia may have gained independence over seventy years ago, but these memories still linger in the national imagination. Today such memories of the colonial past are formed by people who never lived in the colony or experienced colonial times themselves, and exist in different shapes and forms: as literature, podcasts, history books and cookbooks, films, photographs, theatrical performances, and public monuments.

Dutch archives are filled with colonial images that pop up time and again in the public domain and often serve to evoke a distinct nostalgia for ‘the good old days’. Many of them strongly suggest close ties between white colonisers and the colonised, and thus keep the myth of racial harmony in the colonial past alive, presenting the period as something to be fondly remembered. It is little wonder then, that the ultimate image of a harmonious colonial past contains a white child and his or her babu, a dark-skinned, Indonesian nanny. Such widespread intimate memory stories and images serve to make us forget the troublesome realities, and the prevailing systems of inequality, sexism, and racism that underpinned the colonial enterprise.

Lighter than Me reflects a recent shift in the collective postcolonial memory of the Netherlands. The novel pivots around two iconic female Indonesian figures who feature in almost every literary or personal memory story about the Dutch East Indies; the ‘babu’ and the ‘njai’. European families in the colony usually employed Indonesian women and girls to look after their children and many of these children kept very fond memories of their babus. Indeed, the Indonesian substitute mother was often closer to these children than their biological mothers. Nevertheless, she was treated like any other employee and was counted as one among many domestic servants.

In view of the closeness between the nannies and the white children in their care, it is no surprise that babus figure prominently in Dutch (post)colonial memory. The position of the njai, however, was, and remains, much more controversial. In colonial Indonesia it was not unusual for unmarried white men to live with a local woman, or njai, with whom he often had children. As the mother of the white man’s children, a njai belonged to the family but was seldom recognised as such.

Shifts in postcolonial remembrance

Lighter than Me emerged in the context of recent intensifying critiques of Dutch colonialism. Critiques of colonialism have deep roots and extend back to anticolonial movements within countries such as Indonesia, as well as broader international condemnation of colonialism. One challenge to nostalgic views of this past came from the research program ‘Independence, Decolonisation, Violence, and War in Indonesia, 1945-1950’. In 2022 the program’s extensive investigations led to the devastating conclusion that:

The Dutch government and military leadership deliberately tolerated the systematic and widespread use of extreme violence by Dutch soldiers in the war against the Republic of Indonesia.

Public debates about the ways in which the Dutch operated in the former prized colony continue to cause controversy and can lead to fierce arguments among social groups who have different perspectives on the colonial past, such as military veterans, descendants of people who were born in the colony, historians, and politicians. The current steady stream of critical investigations, disturbing revelations, and lawsuits has put pressure on the postcolonial culture of remembrance: the nostalgic image of the once-cherished ex-colony has been severely tarnished.

For many Dutch people, colonial memories have become shameful, overshadowed by guilt and regret. Yet, recent research has also shown that more than half of the Dutch are proud of their colonial past. Many archaic, romanticised clichés about the colonial past linger on and co-exist with critical, anti-colonial representations of the Dutch East Indies. Lighter than Me was first published amidst this postcolonial struggle around understanding and representing this history.

A new emphasis on subaltern Indonesian women

The novel represents Isah – a njai – as a respectable woman. This is in stark contrast to most colonial Dutch literature, in which the njai is portrayed in an utterly negative light. She embodied exotic and dangerous sexuality, was believed to threaten white women and seduce and corrupt naive white men. This demonising image of the njai served as a warning against the social processes of racial mixing, which had been normalised and accepted in the Dutch East Indies for centuries. Under the influence of emerging eugenic ideas from the late nineteenth century onwards, miscegenation or sexual relations between those from different racial groups, especially if one was white, was considered vile and taboo since it was believed to cause Europeans to degenerate. Njais were often 'discarded' and exchanged for a white woman whom the Dutch man legally married. Just as often, her children were taken away from her. Isah represents the fate of many Indonesian women and girls in the colony.

In Dutch collective memory Indonesian babus are recognised as caring and nurturing mother figures, and njais are honoured as the ‘foremothers’ of the large mixed Indo-European community living both in Indonesia and the Netherlands. Within this collective memory, however, there is little to shed light on the actual lives of these women. Lighter than Me is the first novel to highlight the precarity and disenfranchised status of Indonesian women working in European households. Rather than reinscribing the mythical, romanticised and/or demonised Dutch cliche, Lighter than Me places the personal lives of njais and babus in a political and historical context. The author of the novel, Michielsen, is Indo-European and herself descended from a njai. She explored her family archives and used what she found as the context for her fictional story.

Although njais and babus appear in almost all Dutch-language stories about the Dutch East Indies, they rarely have a voice of their own. One rare exception is the portrayal of the character njai Ontosoroh by Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer in his famous Buru tetralogy Bumi Manusia. Pramoedya’s njai Ontosoroh is a courageous woman who tries to survive in the colonial regime that eventually breaks her.

The focus of Lighter than Me is not, as is usual in Dutch memoirs, a Dutch person talking about her/his babu or concubine. Instead, Isah takes centre stage and tells her life story in her own voice. Lighter than Me expresses postcolonial criticism by placing Indonesian female characters at the centre of the narrative, making space for figures who were perceived as insignificant in history and who have remained invisible in official colonial history.

Michielsen portrays Isah as a woman rebelling against and suffering under gender conventions and colonial rules, a woman who chooses her own path in life, explores her sexuality, and who faces the sometimes-disastrous consequences of her decisions. Although the book does not have a happy ending, Isah maintains her self-respect until the end, which is underlined by the novel’s narrative construction. The illiterate Isah tells her life story to a ghostwriter so that her life will be recorded and saved. By doing so, she claims a place in history for njais and babus.

Lighter Than Me gives us a new kind of cultural memory, a kind of public remembering of the colonial past that is currently emerging in the Netherlands. It is a postcolonial attempt to decolonise the memorialisation of the former Dutch East Indies. In doing so, the novel contributes to decolonising the archaic, nostalgic, and often deeply racist memories that still circulate in Dutch culture.

Pamela Pattynama (pattynama1@gmail.com) is Emeritus Professor in Colonial and Postcolonial Literature at the University of Amsterdam.