The National Museum of Indonesia is perpetuating colonial narratives and needs to actively engage with younger generations

Sadiah Boonstra

In 1778 the Bataviaasch Genootschap voor Kunsten en Wetenschappen or Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences was established in Batavia, now Jakarta. The exclusively male Board of Directors, was selected from among the officials of the colonial government and the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC). Ninety years later, in 1868, the Society opened the Batavia Museum to visitors by appointment only. The historian Katharine McGregor observes that it is unclear whether Indonesians had access to the museum or if access was reserved exclusively to Europeans. The museum had more or less the same function as its colonial counterparts in the Netherlands: to showcase the riches of the colony.

With the adoption of the Ethical Policy in 1901, the Batavia Museum increasingly became a place for knowledge and education about the Indonesian archipelago. In her study of Dutch culture in the Netherlands Indies, Frances Gouda has shown that the Dutch used the museum to present an image of itself as a benevolent colonial power, positioned themselves both as rulers of a vast territory of diverse of cultures, and caring custodians of these cultures. In the early decades of the twentieth century, the colonial government became increasingly involved in the Society and therefore the museum.

In 1949 after a four year war and under heavy international pressure, the Dutch acknowledged Indonesian sovereignty and the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences became the Lembaga Kebudayaan Indonesia (Institute of Indonesian Culture). Its motto was ‘to promote such cultural studies as are useful to increase knowledge concerning the Indonesian archipelago’. In 1962, coinciding with the transfer of West-Papua to Indonesia, the museum was handed over to the Indonesian government and renamed Museum Pusat (Central Museum). In 1979 it was renamed Museum Nasional Indonesia (National Museum of Indonesia, MNI) and this remains its name today.

Colonial collecting and exhibition practices

The Batavian Society collected objects and determined whether such objects would remain in Batavia or be sent to museums in the Netherlands. The collections largely went to museums in Leiden, such as the Royal Cabinet of Rarities, which became the Ethnological Museum, and is now part of Wereldmuseum. Collections also went to the Royal House and the Colonial Museum, later Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, now also part of Wereldmuseum, as well as to provincial museums. When the Rijksmuseum was opened in 1885, some Leiden collections were moved to Amsterdam with those sent to the Rijksmuseum deemed to be national-worthy as opposed to ethnological objects.

At times the Ministry of the Colonies intervened in this exchange and selection process. One such example included the ministry issuing a demand that the objects looted from Lombok were sent to the Netherlands and not to Batavia. These objects were subsequently displayed at the Rijksmuseum as ‘the Lombok Treasure’. Objects sent to the Netherlands included those captured as war booty that could cover the costs of the war through sale at auctions, and powerful treasure or heirloom objects the Dutch considered could not be left in the hands of the local population, such as pusaka.

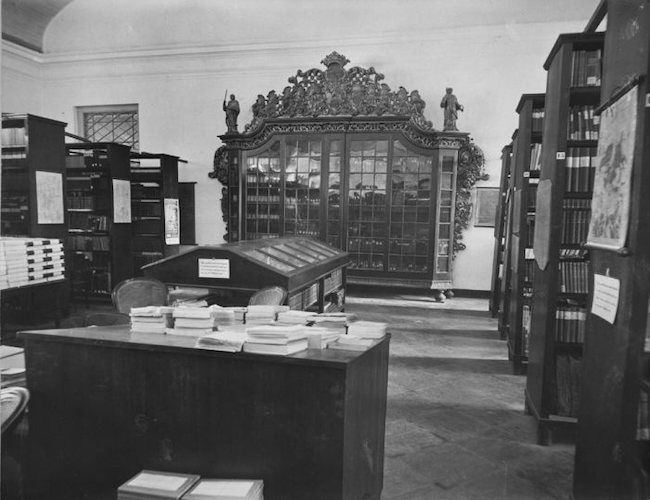

In her recent unpublished MA thesis Heritage in transition: A comparative study of the management and activities of the Batavian Society of Arts and Sciences and the National Museum of Indonesia Tania Anjani Maulana (2023) shows that in early museum displays objects were arranged by category. Photographs indicate for example an archaeological room, a bronze and copper room, a regalia room and ethnography halls. The categorical approach together with the apparent lack of labels or descriptions suggests that the intended museum audience was not the wider public. Rather it was a small group of academics and experts for whom the collections served mostly as a source of knowledge aligned with the Society’s motto to promote cultural studies.

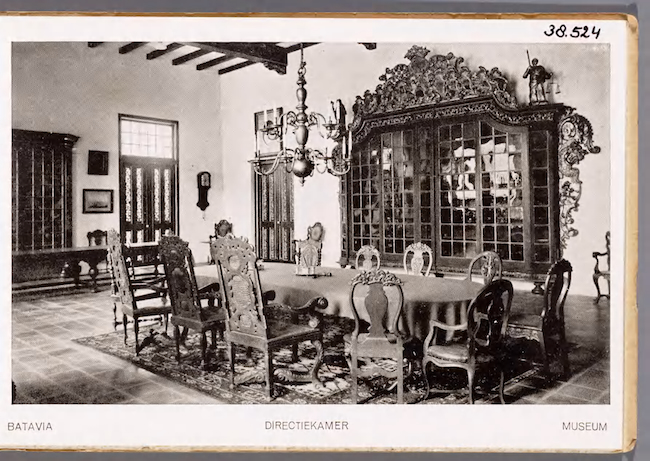

Maulana points to postcards from the 1930s depicting photographs of the interior of the museum. The postcards, sent to family and friends, accentuated the grandeur of the museum, its interior and collections. This suggests that the museum also sought to convey colonial prestige.

The persistence of colonial framings

Between 1949 and 1972 the exhibition displays remained largely the same and after 1962, MNI did not actively focus on acquisitions. When a number of objects were returned from the Netherlands after the Joint Cultural Recommendation of 1975, as scholars Panggah Ardiyansyah and Wiesky Sapardan, and Jos van Beurden (2021) observe, these were used for national identity-building purposes. The continued colonial focus on cultural collections was refashioned for the purpose of reflecting the national motto of ‘Unity in Diversity’. As McGregor argues ‘… displays of diverse ethnic cultures are contained within a national framework to convey the message to Indonesians that “together we are one”.’ The map of ‘ethnic types’ McGregor is referring to was painted by Mas Pirngadie (1875-1936) and is still on display in the museum in the section titled ‘Becoming Indonesia.’

When the displays at the MNI were revamped in the late 2010s, Dutch colonial values and perspectives continued to be reflected in the nationalist presentation of objects in the museum. The museum continues to apply categories developed by the Batavian Society including, prehistoric collections, archaeological collections, ethnographic collections, numismatic and heraldic collections, geographical collections, ceramic collections and historical collections.

The modernist, Darwinian linear approach to history and humanity of the colonial period is still evident in current exhibition narratives. Scholar Adieyatna Fajri has recently argued that the interplay of these narratives with the museum’s role in national identity building has led to the marginalisation of colonial violence, including that against the Banten sultanate in 1808.

This replication of colonial values within the present-day MNI can be understood through the distinction Walter Mignolo makes between decolonisation and decoloniality. He claims that decolonisation is the moment local elites take over the colonial government. Decoloniality by contrast refers to unveiling power structures as well as social, cultural and economic structures that remain unchanged. Coloniality by extension entails the perpetuation of colonial structures and values.

The need for drastic change

Twenty-five years after the reform movement, which included efforts to dismantle the New Order regime’s tight control of history, younger generations are bursting with impatience to visit museums that cater to their interests and their desire to understand their history and therefore their identity in a deeper and more complex way. They are looking to marvel at the beauty and richness of Indonesian art and culture, and to immerse themselves in history presented through a critical lens.

Inspired by global movements some want justice for historical wrongs and accountability and transparency with regard to history, and crave to see this reflected in museums too. The original function of the MNI as a tool of empire that enabled the Dutch colonisers to ‘better’ exploit and rule the colonised and the replication of colonial values in nationalist framings in the museum, no longer suits the needs of the well-educated and critical younger generations. In response MNI needs to transform into a public space, to one where history can be renegotiated and new meanings created for the objects, in dialogue with its audiences.

In a step towards the rewriting of histories of objects, the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology established a new mechanism negotiated with the Netherlands to deal with the request and return of objects collected in colonial contexts. In July 2023 this process resulted in the return of statues from the thirteenth century Singosari temple taken by the Dutch in the early nineteenth century; objects looted during the Lombok war in 1894; a keris seized at Klungkung in 1908 and a collection of modern Balinese art.

The repatriation of objects is a positive step forward in the decolonial story for our museums, however a large gap remains between adopting a decolonial policy and exhibition making practices. The newly created Indonesian Heritage Agency (Badan Layanan Umum Museum dan Cagar Budaya) is focused on addressing this. The Agency merges the management of eighteen museums and 34 heritage sites, including MNI, under the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology. Further to this, discussions about the future of returned objects are taking place amongst academics, artist, history aficionados and to a lesser extent in the public square.

Reimagining the museum as a decolonial space

In September 2023, a massive fire ripped through sections of the MNI leading to its extended closure. As the museum deals with this crisis, its decisions about what to do with the repatriated objects is at a crossroads. Whilst undoubtedly devastating, the fire also presents an opportunity to rethink and create new meanings and ways of framing not just the objects returned from the Netherlands, but the colonial legacy of the 200,000 objects in the collection. The MNI could seize this chance to revisit the history of its collection. To understand how these objects were sourced and collected, by whom, for whom, and with what purpose.

These collections need to be staged and displayed for an entirely different visitor in an entirely different social, political and economic context. The MNI needs to address the history of colonial traditions of the collection and displays and how this was connected to colonial dominance. If these actions are taken the MNI could become a more dynamic public space and a platform for the preservation and mutual creation of culturally diverse memories.

Sadiah Boonstra (sadiah@sadiahcurates.com) Post-doctoral Researcher VU University Amsterdam, Honorary Fellow Melbourne University.