After leaving Indonesia in the bitter fallout of the attempted coup of 1965, Lien Lee dedicated herself to teaching Australian students about her homeland

Virginia Hooker

She had a drive and passion for teaching and ... ability to get amazing results for her students. We learned so much more than the language – culture, traditions and politics as well’. This is how Lisa Buckingham summed up her experience of studying Indonesian language at high school with Mrs Lien Lee. Lisa said her teacher’s dedication and commitment rubbed off on her students and made them want to do their best. Lisa studied Indonesian between 1990 and 1995 and did exceptionally well in her senior high school examinations. She was offered places at several Australian universities and entry to law degrees. But her love of Indonesia and its language steered her away from law and she enrolled in an Arts degree at the University of Melbourne, majoring in Indonesian language as well as history and politics.

Lisa said that one of the attractions of studying with Mrs Lee was participating in special study tours which her teacher organised for them to experience life in Indonesia and to practise their language skills. Before even leaving school Lisa had direct experience of her country of study and the strong desire to return. On a two month stay in Indonesia while at university she had a lengthy stint working in a village in Central Kalimantan as a member of the Australia-Indonesia Institute’s annual Australia-Indonesia Youth Exchange Program. Her in-country experience, strong academic background and solid language skills gave Lisa the edge in many of the positions for which she applied after graduating with a first class honours degree. She accepted a position in the Department of Defence and for the next five years worked in Indonesia-related fields.

Lisa Buckingham is not the only one of Lien Lee’s students who continued to study Indonesian after leaving school. A high proportion of them were inspired to seek careers in Indonesia-related fields as economists, analysts and academics. Several went on to become Indonesian teachers themselves. Lien’s students ascribe their love of Indonesian and their desire to continue their studies directly to their teacher’s approach and dedication. Considering that in 2010 the number of students across Australia studying Indonesian in their final year of high school has halved since 2000, hers is a truly remarkable achievement.

Lien was not always an Indonesian teacher. Before 1966 her life in Indonesia was set on a very different path until a quirk of fate intervened. Lien’s life-story is moving and the challenges she faced might have overwhelmed many others in her situation. But for Lien challenges and obstacles are there to be overcome, usually in a way which helps others. Her former colleagues and students regard her with warm affection and all admire her intelligence and enthusiasm. These were the qualities she brought to her new life in Australia and to her teaching career.

Growing up in a new nation

Thé Lien Nio was born in Central Java’s capital, Semarang, in 1940, while Indonesia was still the Dutch East Indies and soon to be occupied by Japanese forces. Her family were Chinese immigrants to Java in the nineteenth century who settled and blended in with the local cosmopolitan community. Lien’s father established a business printing exercise books for schools and was able to raise his nine children simply but comfortably. What was unusual was that Lien’s parents prepared all their children, including their daughters, for higher education by giving them private lessons in Dutch and sending them to a private Christian high school. Although none of the female members of her mother’s generation had studied beyond secondary school, Lien’s family supported her decision to study law at the new University of Indonesia, where she enrolled in 1957.

Lien moved from a sheltered, provincial life to the much more competitive and heady atmosphere of Jakarta in the late 1950s. President Sukarno was under political and economic pressure as the fledgling nation struggled to meet the expectations of its citizens who had given so much to gain their independence. Lien’s generation was fired by the idealism of the spirit of the revolution. They believed it was their responsibility to help educate their fellow Indonesians so that all could work towards a better and more stable future. When she graduated, Lien worked with one of the law professors at the University of Indonesia and also taught law part-time at Res Publica University (later known as Trisakti). There she met her future husband, Lee Han Koen, a young lecturer in the economics department, led then by the activist and academic, Professor Ernst Utrecht. In 1963 Lien’s career took a very different turn when she was invited to join the State Secretariat. Her move was linked to Sukarno’s decision to appoint a new Minister of State, Oei Tjoe Tat.

Late in 1963, Sukarno chose Oei, respected for his integrity and intelligence, to advise him and the Presidium (Deputy Premiers Subandrio, Leimena and Chaerul Saleh) in the State Secretariat. Oei had the freedom to select his own staff and when Lien was recommended to him he appointed her as his personal legal assistant. Minister Oei remained in this post through the grim period of the attempted coup of September 30 1965. Sukarno’s last task for him was to join a fact finding commission to investigate the numbers of people killed in the violent aftermath.

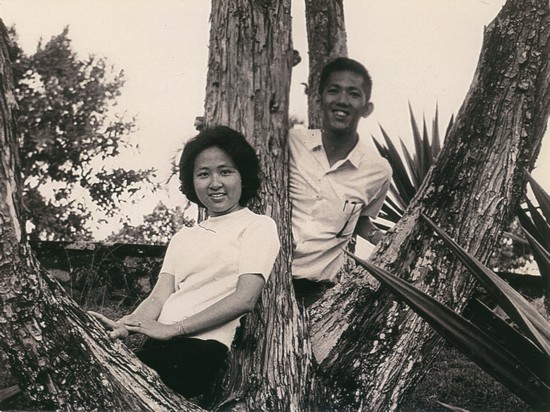

|

Lien and Han Koen Lee married in 1968 shortly before leaving Indonesia for MelbourneLien Lee |

When General Suharto assumed full administrative powers in March 1966 it was clear that a new order was indeed being set in place and those who had worked with or near Sukarno came under suspicion. The new regime especially targeted Indonesians of Chinese descent and many disappeared during this period. Minister Oei was detained in March 1966 and imprisoned for the next eleven years. In a typical understatement referring back to that time Lien says, ‘It was best for us to leave the country.’

Starting again

Dr Herb Feith, devoted scholar of Indonesia, had gone to Jakarta in 1967 to work for one year as a visiting lecturer at the University of Indonesia. Then engaged to be married, Lien and Han sought Herb’s advice about their situation and he responded by urging them to apply to go to Monash University where he taught politics. But immigration procedures were, as now, quite complicated. Even with Herb’s backing Han Koen needed all his powers of persuasion to get the appropriate papers. In March 1968, as newlyweds and with only a few belongings, Lien and Han Koen finally arrived in Melbourne. Herb was there to meet them in his ancient Holden.

Herb and Betty Feith remained close and stalwart friends of the Indonesian couple until Herb’s tragic death in 2001. But he lived to see them become Australian citizens in 1974 and Han Koen became a highly respected investment manager with his own award-winning firm. Lien joined the staff of PLC (Presbyterian Ladies College) in 1979. By then she was the mother of two young daughters so at first she worked part-time. She had studied part-time at Monash University for her Diploma of Education. It was Joan Montgomery, the perceptive and astute Principal of PLC, who recognised in Lien the dedication to excellence which she wanted in her staff.

|

First year in Melbourne with Herb and Betty Feith and family (far left); Budiono, now Vice-President of Indonesia(far right); and Australian landlady Mrs Jochimson, who became one of the family.Lien Lee |

Joan Montgomery presided over one of Melbourne’s oldest and most respected private schools, known for its commitment to excellence in all aspects of education. The school had a particular respect for foreign language learning (not always the case in contemporary Australian schools). The language department at PLC had a strong Head and a group of gifted teachers. Joan appointed Lien to teach Indonesian which at that time was the only Asian language offered there. Lien came into a supportive environment of experienced, professional colleagues with the confidence to push the boundaries if it would help their students learn. She taught at the school for 26 years, only retiring when her daughters had children so she could help them as a hands-on grandmother.

Dr Olivia Clarke joined PLC a few years after Lien and taught Indonesian with her for the next 13 years. Now working as a specialist consultant for educational services, Olivia was impressed by Lien’s uncompromising commitment to excellence. She says that Lien set very high standards for herself, her staff and her students. Another PLC colleague, Helen Buckingham, who started teaching history and politics at PLC in 1987, later became careers adviser at PLC, a role which allowed her an overview of the school and the progress of individual students. She herself noted – and heard from students – that Lien was an outstanding teacher who built an excellent relationship with her charges. These factors translated into outstanding matriculation results. There was a circular effect as students realised that working with Bu Lee (as the students called her) could earn them high marks in their final exams and thus her classes grew and Indonesian language at PLC thrived. Under Lien’s leadership 10-15 students sat the matriculation exams in Indonesian each year and the marks of her students were always the highest in Victoria.

Intellectual challenge

There is a widely held misperception that Indonesian is an ‘easy’ language which can be mastered quickly with little effort. It is true that Indonesian does not have tones or a script like Chinese. But it has its own complexities of syntax, modalities, and difficult systems of affixation. To reach native-speaker level requires complete immersion in the thought-world of Indonesians, most effectively achieved by being in Indonesia.

Lien recognised the importance of engaging her students in the intellectual challenge which learning formal, standard Indonesian requires. Students quickly realised that the subject was not an easy ride. Lien explained the standards needed and the amount of work required to achieve them. Senior students were encouraged to use Indonesian (without recourse to English) for their in-class interactions. Lien set her students many tests so they could assess their progress and assignments were marked and returned without delay.

But Lien’s approach to teaching language was more than language alone. Indonesia was embraced and experienced in every possible way. History, society, culture and food were ingested and every level of Indonesian classes prepared performances for the celebration of Indonesian Independence Day. Lien’s colleagues remember the impression these celebrations made on the rest of the school and the pride Lien’s students took in their achievement.

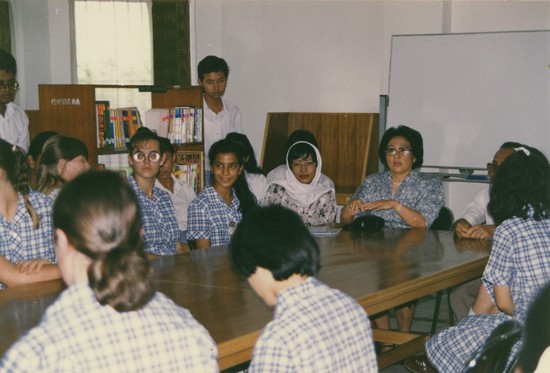

|

Lien and her students visit Jakarta’s private Al-Azhar school as part of their study tour of Indonesia in 1987Lien Lee |

For the girls, the highlight of their Indonesian experience at PLC was the two week study tours of Indonesia which Lien organised for 25 students every two years. Olivia Clarke accompanied Lien on three of these tours, which she described as ‘life changing’ for the students, with itineraries ‘carefully structured to provide critical understanding of Indonesia, its people, history and traditions’. The girls were exposed to many different sides of Indonesia in urban and rural contexts and were guided by Lien on appropriate behaviour, including delivering speeches in Indonesian. Olivia Clarke notes that the experience of these tours helped shape the careers that students later chose.

A bridge to the future

Lien’s teaching years mirror the pattern of growth in Asian language interest in Australian schools and tertiary institutions. Her first years of teaching in the 1980s saw little general interest but this increased steadily during the 1980s. It culminated in a boom period from the early 1990s for about a decade when there was federal government support through policies and funding. Lien’s best students, like others around the country who began their tertiary study at this time, were nurtured at universities with advanced intensive courses and in-country programs. They were highly skilled graduates who were employed by government and the private sector to use their Asian expertise. Today some of them work in senior positions for international agencies and for private companies in Southeast Asia, Europe and the United States.

But circumstances change and coinciding with Lien’s retirement from formal teaching came a falling away in government funding. Terrorist activity in Indonesia raised new security concerns which made it almost impossible for schools to take their students on study tours or for teachers to undertake specialised in-country training. These two factors, plus others not yet fully understood but including hostile media reports about events in Indonesia, have contributed to a drastic decline in the numbers of Australian students studying Indonesian at secondary and tertiary levels. What we do know is that in 2009, it was estimated that 99 per cent of Australian school children studying Indonesian dropped the language before reaching the final year of high school. Veteran journalist, Hamish McDonald, himself an Indonesia expert, has warned that over the next decade ‘Indonesian is heading towards extinction as a year 12 subject’.

|

Lien and her senior students of Indonesian in the early 1990sLien Lee |

Indonesia’s proximity, complexity and size demand Australia’s attention and invite the creation of mutually beneficial partnerships in areas such as education, health, sustainable development and defence. To achieve this Australia requires a reservoir of specialists who can analyse the history, politics, society, economy and religions of Indonesia. Their ability to work effectively in either country is essential to productive interaction. In 2008 an imaginative program to directly link Indonesian schools with counterparts in Australia was launched. Teachers had been frustrated that security concerns had effectively stopped study tours, like those organised by Lien, to Indonesia.

Known as the BRIDGE (Building Relations through Intercultural Dialogue and Engagement) program, supported by the Myer Foundation, AusAID, the Australia-Indonesia Institute and the Asia Education Foundation, pupils and teachers in 46 Australian schools and 47 Indonesian schools now use computer links to talk directly with each other. The aim is to develop on-going collaborative projects which will improve language and intercultural skills of children in both nations. Indonesian teachers and principals are also spending several weeks working in the schools of their Australian partners, sharing ideas about teaching and learning and improving the Indonesian language abilities of young Australians. Results have been so encouraging that the program is being extended.

The BRIDGE program promises to rekindle interest in learning Indonesian language. It has already proven that direct contact between Indonesian and Australian schoolchildren shatters negative preconceptions and enables mutual, more positive connections to be developed. The experience of having Indonesian teachers in Australian classrooms, even for relatively brief periods, has boosted the confidence and morale of Australian teachers. This may prove to be the stimulus that Indonesian language learning needs to recover lost ground.

The experience of Lien’s former students and colleagues suggests that the motivating force of a dedicated teacher is the essential ingredient in successful language learning. They recognise that it was Lien’s commitment and passion, her insistence on high standards and hard work which combined to inspire students to give of their best. But the PLC example also suggests that a successful language program is achieved when a range of factors can be brought together – a supportive principal and school environment, supportive fellow teaching staff, a gifted and committed teacher dedicated to achieving the best possible results, and responsive, hard-working students. The journey from the Republic of Indonesia’s State Secretariat to a school in Victoria was long and demanding. But those who know Lien Lee are very grateful it was made.

Virginia Hooker (Virginia.Hooker@anu.edu.au) is a Visiting Fellow in the Department of Political and Social Change, College of Asia and the Pacific, The Australian National University. She thanks Lien and Han Koen Lee for agreeing to share their story with her. She also acknowledges the very kind assistance of Olivia Clarke, Helen Buckingham and Lisa Buckingham. Peter Hamburger and Charles Coppel provided vital background information. Details of activities fostered by BRIDGE can be seen at www.bridge.edu.au.