A contemporary artist brings new life to a moribund Indonesian theatre genre

Margaret Chan

Wayang beber with Dani Iswardana and Tri Ganjar Wicaksono, 2006Dani Iswardana |

Dani Iswardana is single-minded about his mission to inject new life into wayang beber, perhaps the oldest form of Indonesian narrative theatre, but now described as a dying art. The intensity of his purpose buoys Dani through long stretches of painting when food is forgotten and his work, fuelled by coffee and cigarettes, is all that he cares for. However Dani has gone for years without producing anything, because he will work only when the creative spirit possesses him. Painting for money means nothing to him, and the everyday demands of making a living have no place in his creative practice.

Wayang beber might be translated as ‘stories unfurled’. It is a form of performance that uses a scroll about four metres long, painted with scenes from a story. The scroll is mounted on two spindles and is rolled from one spindle to the other to reveal the story scene by scene. Narration is provided by a story-teller who is either hidden behind the screen or sits in front of it, pointing to the pictures with a long stick. In Dani’s hands, this ancient art form is being transformed into a medium for exploring the complexities of everyday life in contemporary Indonesia.

Ancient origins

Wayang beber is believed to have been created in the first century CE by a ruler of the Hinduised kingdom of Mamenang in Kediri, East Java. It appears to have originated in the form of pictures painted on palmyra leaves, illustrations of the heroic exploits of the king’s forefathers for the edification of his courtiers. Later, the use of still pictures evolved into a form of narrative theatre using a continuous scroll and the voice of a story-teller working to the accompaniment of music. When Islam came to Java in the sixteenth century wayang beber fell out of favour. Islam proscribes the use of images to celebrate heroes and gods, and so it has been argued that the more ephemeral shadow puppet was introduced in its place. The insubstantial shadows cast by the stylised puppets of wayang kulit seem to have been more in accordance with the traditions of Islamic art.

Today scholars know of only two traditional sets of wayang beber still in existence. Eight scrolls are located in the district of Gunungkidul, Yogyakarta, and six scrolls are kept in the district of Pacitan, East Java. Researchers date these scrolls to the eighteenth century at the latest, with some suggesting that four of the Gunungkidul scrolls may go back to the Islamic Mataram kingdom of the seventeenth century, when its capital was located at Kotagede.

These ancient scrolls are so fragile and precious that they are no longer used in public performance. The Gunungkidul scrolls are used only for ritual purposes, and issues of performing rights present obstacles to the performance of the Pacitan scrolls. The custom is that the owners of the scroll, not the story-teller, hold performance rights. Present-day performances of the Pacitan scrolls are by a thirteenth generation descendant from Kediri kingdom days, but the scrolls themselves are owned by a twelfth generation family. As a result, the Pacitan story-teller tells his stories with a digitally printed, plasticised scroll.

In 2005, artists from all over Indonesia gathered in Gelaran village, the home of the Gunungkidul scrolls, and agreed to work to preserve wayang beber. For them, this did not mean reviving wayang beber as a performance tradition but, rather, faithfully duplicating the ancient scrolls to be displayed in museums. But even in this ambition, the gathering came up against obstacles. Prayitno, a member of the group, was quoted in a Jakarta Post report of 14 October 2005 as saying, ‘The problem is we have not yet found the right paper or the right artist. We want it to be exactly the same and long lasting.’

Elsewhere, the art form of wayang beber-style painting has undergone changes. At the Institut Seni Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of Art) in Surakarta, students learn how to draw pictures on canvas and glass in the style of wayang beber, and there are now artists who specialise in this medium. They sell their works as art pieces – stills, not moving pictures, on a narrative scroll that has to be unfurled before an audience for its story to be told in real time. The ancient tradition of wayang beber performance now only exists in the Pacitan performances based on digital copies of the original scrolls.

Re-interpreting tradition

This is where 37-year-old Dani Iswardana comes in. Dani, who is based in the central Javanese city of Solo, has created four original wayang beber scrolls that are intended for use in performance. Three were painted in 2005 and are complete: Suluk Banyu (The Chant of Water) tells of the commercialisation of village water supplies by bottling companies; Pasar Kumandang (The Spirit of the Traditional Market) is about the remorseless urbanisation of the village economy; and Lesung Jumengglung (Pounding Grain) tells how the old village spirit of community has been eroded by modernity. Farmers use chemicals to fertilise the soil and fell trees to build homes. The young leave for the city to find employment.

The first two scrolls are currently being performed by story-teller Tri Ganjar Wicaksono, who began collaborating with Dani in 2005 when he was only 15 years old. Performances take place only when there is a commission, and these are few and far between. The third scroll was inadvertently lost when Dani took it to Singapore in 2007. The fourth scroll was created when Dani was artist-in-residence at the Singapore Management University in late 2009. This scroll is fully drawn but has not been completely painted, and it has not been given a proper title. It tells of a visit to Singapore by Semar, the corpulent wayang clown much beloved of Javanese audiences.

|

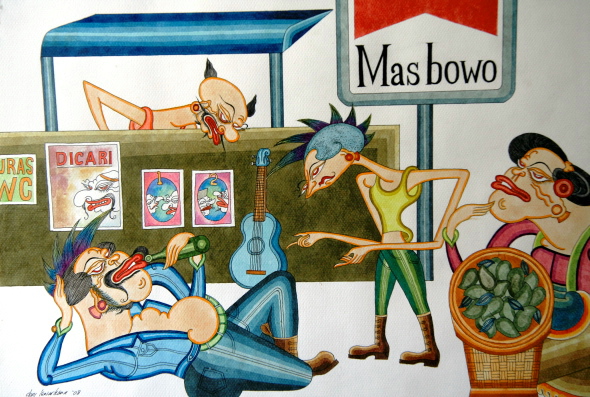

Punk kids in an Indonesian village, acrylic on paper, Dani Iswardana, 2008Dani Iswardana |

Dani and his scrolls have not been embraced by the artists who want to preserve traditional wayang beber as a museum exhibit. For them, wayang beber should tell only the Panji story, the subject of the old scrolls. This is the story of Dewi Sekartaji, a princess who ran away from her father’s palace and was pursued by adventurers seeking her hand in marriage. The hero of the story is Joko Kembang Kuning, who undergoes a series of trials in his search for his bride-to-be. In wayang beber, this story is expected to be told in six scrolls, each with four scenes. Although the story is completed in 24 scenes, wayang beber lore dictates that only 23 may be shared with the public. The final scene must never be shown.

According to wayang beber custom, each show is regarded as ritual, with the story-teller having first to make offerings to the gods. How can Dani, the purists ask, with his drawings about water from village springs gurgling out of office water-coolers and punk Indonesian kids in supermarkets, ever be considered a part of this hallowed tradition?

Taking issue with the purists

But what remains of this tradition? To date there is the Pacitan story-telling using a digitally printed scroll; wayang beber-style paintings on canvas and glass; and an incomplete set of copies of the Pacitan scrolls, painted on cloth (not the bark paper of ancient times) hanging in the Wayang Museum in Fatahillah Square in downtown Jakarta. These are pictures, framed behind glass, hanging lifeless along a poorly lit wall. To Dani, these images do not constitute wayang beber, because wayang beber has to be performed to come alive. This is why, once he has painted a set of scrolls, Dani surrenders them to the story-tellers. To him, the story-teller, not the artist, is the lynchpin of the ancient tradition.

The narrow insistence on clinging to ancient scrolls has worked against the spread of wayang beber as a living art. Unlike other forms of Indonesian wayang, where practitioners, be they puppeteers or actors, can travel and take the knowledge of their theatre to all of Indonesia, purist performances of wayang beber remain trapped within the restricted access to the antique scrolls, or to copies of them. But Dani can travel with his scrolls. He rolls them up and carries them along with him, inviting narrators to interpret his drawings in story to an audience. In this way Dani believes that he upholds the true spirit of wayang beber.

Dani also holds that his stories about water privatisation and the urbanisation of villages embody themes that are true to the spirit of the Panji stories. For while the ancient wayang beber scrolls tell in 24 scenes the straightforward story of a prince looking for his princess, the wider Panji literature actually consists of a rich collection of independent stories united by the common theme of the search for a lost essence. This, says Dani, is precisely what his scrolls are about. For example, Javanese religions use water in purification rituals. Isn’t something lost, asks Dani, if this holy water comes out of plastic bottles?

In his scroll of Semar in Singapore Dani features Ki and Nyi Brayut, two mythological characters portrayed with baskets filled with fairy babies. The pair constitutes the Javanese symbol of fertility. In Singapore, the Brayuts are lost. The babies escape from the baskets and wander aimlessly about. Singapore has grown so fast, explains Dani, that it has lost part of its soul, including a love for bearing children.

A recurrent character in Dani’s works is that of the idealistic artist, drawn as a thin figure with moustache and goatee and shoulder-length hair caught in a ponytail. This is clearly a self-portrait, and yes, Dani admits with a snort of laughter, he sees himself as the ever-seeking wanderer. This is why, when he is not working on scrolls, Dani draws on sketch pads. He has been told that he should paint on canvas so he can store and sell his work more effectively, but for him canvas is too cumbersome. He prefers a simple art block that he can carry around with him. Selling his art is not the point of his existence, he explains. He would rather earn a living doing odd jobs so that art can remain a passion.

With only a sketch pad in hand, Dani says he can travel lightly and draw whenever and wherever the mood strikes him. ‘Must wayang exist only in the context of Java?’ he asks. ‘I can go to China, to Iraq; I can be a person of the universe.’ This is what he lives for, to be the true Panji wanderer searching the world for meaning. So far Dani’s work has taken him to Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia in 2007, to Singapore in 2007 and 2009, Shimane, Japan in 2008 and Vitre, France in 2010.

Margaret Chan (margaretchan@smu.edu.sg) is Practice Assistant Professor of Theatre/Performance Studies, School Social Sciences, Singapore Management University.