At Earhouse Songwriting Club music is not only about the performer or performance, but also about the audience and the act of listening

On a cool breezy night in early 2023, I paid a return visit to Earhouse, a small café in Pamulang, South Tangerang, where the Earhouse Songwriting Club (ESC) meets weekly. Every Monday, ESC runs a free songwriting class led by a respected independent musician, Endah Widiastuti, from the acoustic duo and married couple, Endah N Rhesa.

In tonight's class, I paid particular attention to the way each class member performed their songs. On a small stage - just an area marked by a red carpet - anyone could take their turn singing. The songs were varied: sweet pop, folk-rock, or even hip-hop. Everyone was listening carefully and later exchanged comments on each performer’s song. Endah usually offers the first impression about songs before others join the discussion.

Midway through the session, Don, a guy in his early 30s, got up from his chair and walked to the front. The song he was going to play was titled Trauma Irama, which was derived from the name of dangdut (popular Indonesian music genre) legend Rhoma Irama. ‘Tonight, we’re going to play punk songs!’, said Don in a deep voice, trying to sound like a rock singer. Later, I understood that this was a joke. It is, in fact, a song in folk-melayu style.

Don was enjoying his playing, while others were still trying to keep up with the lyrics, ‘Benalu… Benar-benar tak tahu… Tak tahu malu-malu.’ As he reached the last verse others gently began to sing along. When the song finished, the room filled with applause. With a small laugh, Don explained that he sings this one ‘when someone annoys me in the office’. Endah, who was sitting close to the stage, asked Don whether the pitch was too low for him. Don immediately changed the song key to match his pitch.

By now the crowd had grasped the lyrics very well and started to sing along more enthusiastically, letting out a great cheer at the end. Don walked back to his chair, and another participant took their turn.

This is a typical scene on a Monday night at Earhouse. I usually watch somewhat nervously from a seat at the back of the room. As an undergraduate doing research on music at Earhouse, these acts of commentary, critique and knowledge-sharing speak to me deeply. I see these practice sessions as acts of appreciation and community-building. But what do they tell us about the wider Indonesian music scene?

ESC as an alternative community

In 2009, after success touring overseas, Endah N Rhesa opened Earhouse as a way to connect once more with the local music scene in Pamulang. As music lovers increasingly made their way to Earhouse, besides hosting a variety of gigs and events Endah established a series of music clubs. One of them is ESC, which attracts many people and has helped to build a vibrant local music scene in Pamulang.

Earhouse was part of the flourishing of movements in the arts and music in many cities after reformasi (the post-Suharto era in Indonesia). Similar spaces emerged in Yogyakarta, Bandung, Surabaya, and neighbouring cities, Jakarta and Bekasi. These are spaces with overlapping functions, such as a coffee shop, a gallery or even a performance venue. It is usually activated by a community and relates to art, music, literature, or interest in a particular social issue. Independent from government cultural institutions, some scholars have described them as ‘alternative’ and ‘initiative’ spaces.

One of the characteristics these spaces and communities share is their informality, sharing and producing knowledge together and working collaboratively. This practice was clear to see in the everyday musical interactions among members of ESC. Participants could choose to join the class occasionally, without the responsibility to attend every week, for example. After class, they would gather outside the café to talk and share more about music, song writing and its industry. The musical processes were seemingly endless.

Taking on the gatekeepers

ESC emerged as an appreciative community at a time of heightened cynical criticism within the Indonesian music scene led by its cultural gatekeepers such as community front men - senior musicians to casual listeners. In our conversations many of my interlocutors told me about their encounters with ‘musical gatekeeping’ before joining ESC. Their experiences included negative commentary on their performances, a refusal or reluctance to share musical knowledge with each other, and rejection of other’s musical choices.

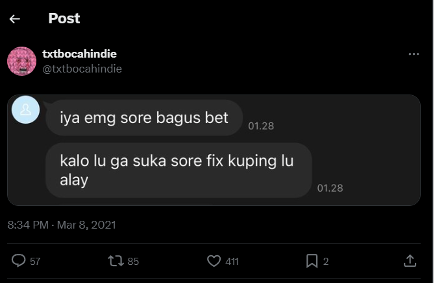

More recently, Indonesians have started to talk about musical snobbery, when someone arrogantly takes pride in their music tastes at the exclusion of others. A music snob is stereotypically portrayed as a person who listens to non-mainstream music, has a know-it-all attitude and disregards mainstream popular music genres, such as pop, dangdut or ballad. This type of attitude annoys many young people who seek an inclusive space in music, where differences are celebrated. With the help of social media, young people started to criticise it, as they could easily spot snobbish behaviour through their posts on ‘X’, formally known as Twitter.

Awareness of this type of snobbery and associated gatekeeping behaviour has extended to include the popularisation among young people of terms such as ‘skena’, literally meaning ‘scene’. Its usage began to circulate widely after the release in 2020 of singer-songwriter Sir Dandy’s song, ‘Polisi Skena’, which translates as ‘scene police’. The song talks about gatekeeping in music and calls for inclusivity in the music scene. A few years later, sarcastic videos emerged on Instagram joking about the characteristics of ‘skena kids’, their fashion, habits and language. Sastra Silalahi, for example, a content creator who pioneered the idea of the videos, helped popularise the word ‘skena’ on the Internet through his Instagram videos.

These ongoing conversations – both through social media and in real spaces like ESC - highlight a deep-rooted problem in the Indonesian musical landscape, which is the lack of mutual appreciation. This relates to what anthropologist Jeremy Wallach once highlighted as a status consciousness and prestige described by the term ‘gengsi’. Wallach observed that Indonesians had a feeling of prestige toward music that is considered superior, like, for example, Western music. Although what is considered superior may change over time, gengsi often socially influenced people to exclude certain music from being listened to and discussed. From my observations of the music scene such status consciousness or gengsi also forms the basis of many gatekeeping behaviours that neglect the variety of musical cultures.

By fostering collaborative learning and appreciation as a key practice in the community, ESC can be seen as a response to these competing situations. It offers a forum to share music ideas without judgement or prejudice and in so doing, challenges the subcultural boundaries in Indonesian music. Their practices are also part of a wider action, as young people and many musicians strive to eradicate stereotypes and gatekeeping in the music industry, leaving gengsi behind.

Toward appreciative futures in music

One of ESC’s more recent members, Vanessa, described the contrast between her experiences here compared to her experiences at a few other arts communities where toxic gatekeeping was still being practised. She enjoys ESC’s inclusivity, the way participants can access each other’s musical knowledge casually and without intimidation, and the support and encouragement they offer each other.

Vanessa’s reflections are like many I have heard from ESC participants. Music is not only about the performer or performance but is also about the audience and listeners. ESC practices sparked our sensibility toward being better listeners. Applause, comments, and encouragement are important gestures in active listening and further build appreciative interactions.

Cultural infrastructure and institutions are mostly focused on giving people access to perform. ESC moves beyond it by expanding their resources to these forms of appreciation. Thus, for me, ESC is not only a community that romanticises leisure or hobbies. It aims for a better future where musicians are well appreciated.

Arya Adyuta (aryajpadyuta@gmail.com) is studying cultural anthropology at Universitas Gadjah Mada.