Female candidates did better than expected in the 2009 general elections

Sarah Shair-Rosenfield

Hetifah Sjaifudian represents Golkar in Indonesia’s lower houseSarah Shair-Rosenfield |

As Indonesia’s democracy moves into its second decade, institutional changes at each stage of electoral development have altered women’s roles in party politics and national legislative representation. Despite a hard-fought battle to require inclusion into the candidacy system through a set of clauses in the electoral and political party laws, women’s groups felt that the Constitutional Court ruling that opened up the nomination lists to voter choice meant that the 2009 national legislative elections were a backwards step.

According to many female candidates and activists, the formal gender quota and placement mandate on ballots were undermined by the introduction of an open-list system that allowed voters to choose ‘around’ the women that the parties had been required to place in winnable positions. But the effect of offering voters the ability to choose their representatives more directly was actually not all bad. Indonesian voters not only continued to vote for women, they voted for them more – resulting in a seven percent increase in the number of national female legislators between 2004 and 2009. Although women are not yet fully included and respected in all aspects of Indonesian political life, they appear to be on the right path.

Making space for women

Gender quotas and placement mandates are two of the most common institutional mechanisms used to increase female candidacy and representation rates. They are popular because they only affect candidacy, limiting interference with democratic voter choice. Quotas rarely meet expectations unless accompanied by a placement mandate, which requires parties to put women into positions where they can be competitive. Otherwise parties could push all the women candidates required by the quota to the bottom of their lists.

Indonesia’s women’s groups, including many female party activists and legislators, have been fighting for greater inclusion in the political system since 2003. But the 2004 election law included only a vague mention of a quota, not a real rule and placement mandate. As a result, parties mostly ignored the quota, and rarely put women into winnable positions. Not surprisingly, the 2004 elections only showed a small increase in the number of women legislators elected.

In 2008, women’s groups and international NGOs managed to convince the lower house (DPR) to pass an electoral law that included both a quota and placement mandate. Although they faced a lot of opposition at first, including claims from some parties that the quota was ‘undemocratic’, eventually the parties in the DPR supported the new law. A challenge brought to the Constitutional Court also ruled in the women’s favour, asserting that the quota and placement mandate constituted justifiable affirmative action.

Still, having a quota and a placement mandate is by no means a panacea. Such measures work best in systems with fully-closed lists, large districts and a small number of parties, where little is left to chance when it comes to which candidates win seats. With relatively small districts and a large number of parties, the Indonesian system really favours only the first and second candidates listed. Indeed, only 28 of the 560 seats of the 2009 DPR went to parties winning at least three seats in a given district – which means that mandated placement is much less effective for candidates in the third position, the lowest position where a party’s first female candidate can be put under Indonesia’s placement mandate.

Unexpected results

Activists and many candidates argued that voters had deliberately chosen not to elect women even where parties had ranked women higher (including in top spots). But this was not really the case. In the top nine parties, there was just a two per cent difference in the rates at which men and women won seats when nominated to the top listed position. Where men were nominated highest, they won seats 52 per cent of the time. Where women were given the top spot, they won seats 50 per cent of the time. The figures get even more interesting if we look at the second position on party tickets. Men listed second won seats 14 per cent of the time and women listed in the second position won seats 18 per cent of the time, for a four per cent difference in favour of women.

A lot depended, though, on each of the parties. Of the top nine in the DPR race, only three – PKB, PD and PDIP – managed greater than a 20 per cent female representation rate. The other six only averaged 6 women in each of their parliamentary factions.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the two conservative Islamist parties, PKS and PPP, have the lowest female representation rates – with PKS the only current party in the DPR to actually elect a smaller proportion of women than in 2004, despite fairly good compliance with the quota and the placement mandate. PPP, the legislative party with the poorest record of quota compliance, actually registered the best improvement of any party outside the top three, nearly doubling its number of female representatives despite a reduction in the party’s overall presence in parliament.

Different parties, different patterns

What explains the high rates of female parliamentary participation in the more successful parties, PKB, PD and PDIP? Each is due to very different reasons, from PKB’s organisational and community ties, to PD’s more systematic campaigning, to PDIP’s historically women-friendly constituency.

PKB boasts a number of high-profile women legislators who are leaders in the influential mass religious organisations, such as Ida Fauziyah who was elected to be the current chairwoman of the Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) women’s organisation, Fatayat, a year after winning re-election to the DPR. The strength of PKB in East Java is largely due to the strength of NU membership in the province, and having visible and well-known Fatayat leaders as candidates undoubtedly aids the party’s election efforts in those districts. When PKB was looking for female candidates for the districts where they expected to do well, they wanted to nominate strong candidates with good ties to their communities – Fatayat members were the easy and effective choice for PKB to stay successful in the region and still try to comply with the quota and placement mandate.

PKB’s record of female electoral success is impressive, especially given the massive reduction in the size of its parliamentary faction, although it failed to fully comply with the placement mandate. There were four districts where PKB fielded at least three candidates but failed to nominate a single woman. Also, in many districts a woman was nominated to the first or second position overall at the expense of quota and placement mandate compliance in the bottom half of those lists. The net effect was a poorer overall legal compliance record but a higher number of women elected from the highest list placements, including nine women nominated to the top spot.

As an election competitor, PD blew away most of the competition, more than doubling its seat-share from 2004 to become the largest party in the DPR. Its performance with respect to its female candidates was also impressive, partly due to the large number of women nominated in the first and second positions on the lists.

|

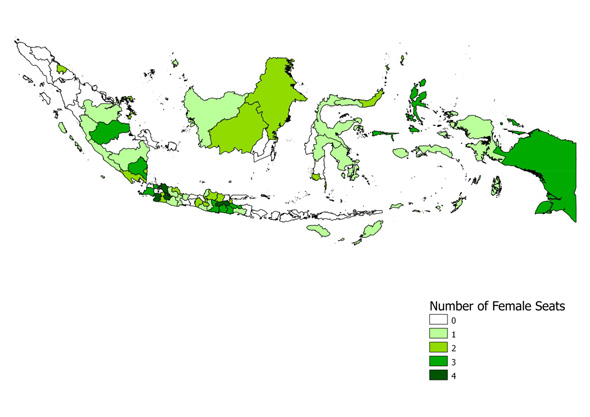

Female Representation across Indonesia in 2009Sarah Shair-Rosenfield |

PD nominated a diverse set of female candidates to top list positions, including a former local legislative representative from North Maluku, the chief medical officer of a clinic in Jakarta, a former Miss Indonesia and a sitting municipal legislator from Gorontalo. In Papua, PD courted Etha Bulo, a sitting female legislator from the Vanguard Party (Partai Pelopor), which was unlikely to make the 2.5 per cent electoral threshold – meaning that Etha was likely to lose her seat despite her local popularity. Etha won the largest number of individual votes and the PD’s first seat in the district despite her placement in the third position on the list.

Of the three best-performing parties, PDIP seemed the most natural fit for female electoral success, boasting some high-profile female activists and a voting base that does not appear to have a strong gender bias. But the PDIP leadership was resistant to implementation of the quota, due in part to chairwoman Megawati Sukarnoputri’s long-standing aversion to gender-based affirmative action policies. In fact, it was not until DPR member Eva Sundari publicly called attention to the fact of gender bias in the party’s candidate nomination process that PDIP leadership eventually agreed to pass the quota.

Even with its fairly strict set of criteria about nomination for national legislative candidates, including a requirement that they have at least a bachelor’s degree, PDIP had no trouble finding highly-educated, highly-qualified women to run for 30 per cent of positions on their lists. Ironically, it had trouble finding equally qualified men to fill the other 70 per cent. In the end, PDIP had near-perfect compliance with both the quota and placement mandate. But just two women, including Puan Maharani, Megawati’s daughter, were nominated to the top position.

PDIP did nominate 21 women in second positions on their tickets, which was high enough to guarantee a seat in many of its traditional voting bases as long as voters chose according to list order. In fact, PDIP voters chose a number of women listed even lower by the party: nine times as many party voters chose out of order to elevate female candidates above men, either to the party’s only seat in the district or ahead of a man listed in the first or second position in a district where it won two seats.

After the election

In ten years of democratic elections Indonesia has increased the number and profile of women in political life and the gains women have made are generally positive. Yet, at 18 per cent, women’s activists in Indonesia can’t afford to cool their heels and simply be satisfied with better representation than they had in the past.

Little by way of gender-specific or women-friendly policy has emerged from the first 18 months of this parliament’s work. Women are often still marginalised in the DPR and on Commissions and – despite the requirement that party central boards be composed of at least 30 per cent women – they still have limited voice in and contribution to party decision-making processes.

It is also clear that female candidates in Indonesia as a group face more divisions than their male counterparts. Female celebrities as candidates and in parliament are criticised for their lack of credentials in a way that their male counterparts aren’t. Older women tend to wear headscarves but younger women, especially from metropolitan areas, do so less frequently. When younger female candidates and legislators Tweet and use Facebook to advertise themselves and push the issues they feel strongly about, they are often accused of ‘unladylike’ self-promotion. In an increasingly pious Indonesia, these behaviours tend to draw the attention of an ‘old guard’ of female legislators who criticise young parliamentarians as harshly as the media and their male counterparts do. A number of these more experienced women are actually concerned with the perpetuation of stereotypes or the perception that women are ineffective and can be pushed around. But they help no one by adding to the chorus of criticisms.

Despite all these impediments, in all but a handful of places the 2009 election proved that direct voter choice does not necessarily stop women from being elected. Indeed, over the past seven years surveys by various organisations have shown steady improvement in Indonesian voters’ willingness to accept female political leaders and in their expectation of what an ‘appropriate’ level of female representation is. In the end, though, parties control much of the nomination process, even in the open-list system. So if more gains are to be made, activists need to focus on pushing for higher positions for women on party tickets and better compliance, as well as for training for female candidates from all parties.

Sarah Shair-Rosenfield (sarahsr@email.unc.edu) is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Her doctoral research focuses on the role of political parties and electoral reform in the process of democratisation.