First a confession: I'd heard of the Australian Clive Williams, the late President Suharto’s enigmatic intermediary, and started searching. But the tale was too hard to unearth – it was also unbelievable. Fortunately, Australian academic Shannon Smith had more time, tenacity and certitude. So now we have titbits of the remarkable secret story and its significance to Indonesian relations with the West for three critical decades last century.

Occidental Preacher, Accidental Teacher: The Enigmatic Clive Williams, Volume One, 1921-1968 is the first in what is to be a two-volume biography. The book is a little of the life and much of the times of Williams who remains elusive despite solid research. It’s academically bomb-proof with 68 pages of notes, an index and references for every assertion, but the target remains largely untouched.

The biography includes a lot about Jehovah’s Witnesses, the 1965 Jakarta coup and Javanese culture. This is entertaining but ultimately, padding, because Smith had problems finding facts to write about a man who left few paper trails.

Born in 1921 into a struggling Geelong family, Williams became a Witness missionary and eventually ended up in Indonesia to preach the word. It was here, aged 34 years, that he quit the church, or was forced out because he was gay.

He settled in Semarang in Central Java, where he ‘emerged with a new identity’ as a chiropractor and English teacher with ‘a number of rich eccentricities’ according to one Australian diplomat – presumably a euphemism for his sexual preferences. Williams’ pupils included the wife and children of an army colonel stationed nearby, a man little known to Western intelligence. That soon changed. The soldier was Suharto, destined to become the authoritarian kleptocrat second President of Indonesia, a job he held for 32 years.

Away from preaching and now into business, Williams was doing well, but he was rarely noticed by visitors. An exception was Australian journalist Frank Palmos who remembered a ‘clever, confident Australian’ who dodged questions about his past. Others remember his size (fat) and ‘plastic teeth’, so not an inviting character – except for who and what he knew.

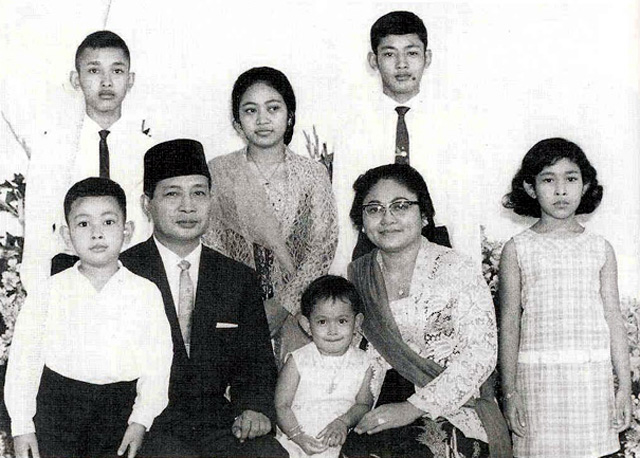

A most unusual friendship had developed between Williams and Suharto. One was a well-travelled homosexual and former Christian tub-thumper from an individualistic Western culture. The other was an unsophisticated, ambitious and corrupt career officer with (eventually) six kids, born in a Central Javanese village and suspicious of foreigners.

Williams was alongside Suharto for much of that time, acting as a conduit for his messages to the fact and gossip-hungry Americans who found the president inaccessible. To them, the guy from Geelong was a ‘straight shooter and reliable interpreter of Suharto’s thinking.’ Though the same can not be said, it seems, for the Australians.

Australian Ambassador Max Loveday (whom one journalist described as ‘a pompous little prick’) only wanted news through approved diplomatic lines, which excluded Williams. Loveday’s successors were more astute, and keen to get wisdoms from a normally closed palace. For the few journalists aware of his role, Williams offered up plenty of scoops helping them to make sense of the intrigues and villainy.

How much did Williams know of the 1965-66 genocide when militias and the army killed maybe half a million real or imagined communists in a nationwide purge after the coup that brought Suharto to power? Williams also hated ‘the Reds’ and war but it seems he said nothing as the blood flowed, making him morally complicit. Comments Smith: ‘Did he help rescue individuals from death or incarceration? We will probably never know.’

In Jakarta, Williams lived in a home adjacent to the president’s compound with side-gate access, often dining with the family. The two men were almost the same age. In politics trust is rare, but Suharto had total faith in ‘Om Clive’ to broker business deals, fix problems that foxed diplomats, interpret foreign news and be a high-level messenger. Smith concluded Williams kept Suharto ‘grounded’ and was ‘a source of unfettered common sense.’ But not a moral compass.

The outsider mastered Indonesian and Javanese, absorbing the culture to become inscrutable and enigmatic. Author Blanche D’Alpuget who worked in the Australian embassy in the late 1960s and early 1970s, recalled that Williams shunned parties and seemed to have adopted ‘a kind of Javanese ingratiating submissiveness.’

Unlike Suharto’s official advisers, the Australian was not in it for money or fame. His and Suharto’s interests were mysticism - explored with ABC journalist Tim Bowden in 1966 - the only time Williams talked on radio. Few photos of him exist. The cropped picture used on the book cover shows a seemingly indifferent bystander in batik having a smoke, hardly a puppeteer. There’s no sense of importance or authority.

Smith has given too much space to Witness history and speculation about why Williams joined the controversial sect that believed in Armageddon; he never spoke of his religious past yet had been a powerful orator and an ‘energetic adherent and proselytiser’.

Suharto passed away in 2008 and was grandly entombed in Solo after a state funeral. His ‘Australian whisperer’ had died seven years earlier aged 80, although where he rests remains unknown. Fitting perhaps, as much of his past also remains buried. The next volume of Smith’s scholarship due later this year will need to be more revealing of the Australian – if that’s possible.

Shannon Smith, Occidental Preacher, Accidental Teacher: The Enigmatic Clive Williams, Volume 1, 1921–1968, Big Hill Publishing, 2024.

Duncan Graham (wordstars@hotmail.com) is an Australian journalist living in East Java. He writes the blog Indonesia Now.