Islamic film is emerging as a new genre in the Indonesian film world

Ekky Imanjaya

A mega film with mega promotion |

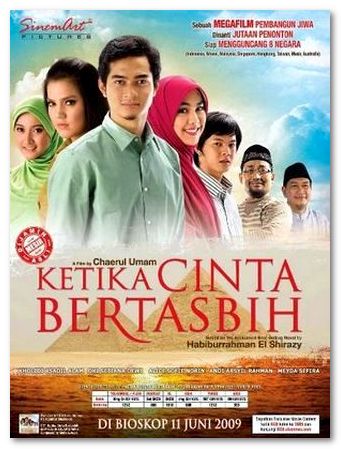

The current star of the Indonesian film is Ketika Cinta Bertasbih (When Love Glorifies God, directed by senior filmmaker Chairul Umam), the latest in a series of Islamic-themed films that are changing the face of Indonesian cinema. The film is based on the bestselling novel by Habiburrahman Syirazi, the author who also wrote Ayat-Ayat Cinta (Holy Verses of Love), another novel which was a huge commercial success when adapted for the big screen. Ketika Cinta Bertasbih (or KCB) began screening Indonesia-wide on 11 June 2009, but even in its pre-production phase in 2008, it was already an Indonesian cinema phenomenon.

Auditions for the film lasted for three and a half months, and took place in nine different Indonesian cities. A TV show was created to enable viewers to follow the audition process, and the grand final was screened nationally on 14 September 2008. The wannabe actors all had to show they could recite the Holy Quran fluently and show that they applied Islamic values in their daily lives. The judging panel consisted of prominent Islamic figures in the arts and entertainment industry, such as the actress Neno Warisman and Habiburrahman Syirazi himself.

The pre-release promotional hype declared KCB would be a ‘Mega Film’, and ‘the first Indonesian film produced in the land of Egypt’. Giant billboards on main streets were part of the promotion. ‘Ready to shake eight countries’ screamed one. Following the movie’s release, the promotion continued: ‘One million viewers after a month’s screening!’ became ‘Two million viewers after two months’ screening!’ Another billboard announced a promotional competition: ‘Win a tour to the places where KCB was shot’.

‘One million viewers after a month’s screening!’ became ‘Two million viewers after two months’ screening!’

With a budget of 40 billion rupiah (around US$ 4 million), KCB is the most expensive film ever to be produced in Indonesia. In the first week of its release, it screened in 148 cinemas across the country, breaking the previous record set by Riri Riza’s Laskar Pelangi (Rainbow Militia, 2008) which appeared at 115 cinemas in its opening week. The sequel, KCB 2 is due for release nationally on September 17, a few days before Idul Fitri.

An Islamic love story

The basic storyline of KCB deals with the problem of how to find a soul-mate in an Islamic way. In the movie, dating or even handshaking between men and women is not allowed if the characters are not married. The story focuses on Khairul Azzam, an Indonesian student at al-Azhar University in Cairo. Azzam comes from a modest family and he has to work, making and selling tempeh and tofu, to support his mother and sisters back in Yogyakarta. He is also a moderate Islamic activist who has a deep knowledge of Islam and applies Islamic values in his daily life. Eliana, the daughter of the Indonesian ambassador, and an actress in the making, falls for him because of his hard work and piety, but Azzam gently rejects her.

One day, Azzam hears about Anna Althafunnisa, a highly educated girl from a respected religious family; he wishes that one day she will become his wife, just on the basis of what he hears about her. But one of his close friends from a rich family, Furqon, has already proposed to her. One day, Azzam helps Anna during a robbery, but still they don’t know each other’s names. Anna also becomes close to Azzam’s family in Yogyakarta. Meanwhile, Furqon is the target of blackmail and becomes HIV positive; but his marriage proposal has already been accepted.

The film is full of Islamic advice and preaching about how to deal with problems of daily life

The film is full of Islamic advice and preaching about how to deal with problems of daily life. It deals, for example, with the debate on polygamy. When Furqon proposes to Anna, she sets two conditions: she will remain in her family’s pesantren (Islamic boarding school), and Furqon is not allowed to take a second wife. ‘I just want to be just like Khadijah (the Prophet Muhammad’s first wife) and Fatimah (the Prophet’s daughter) who were the one and only wives of their husbands for the rest of their lives,’ Anna says. When other character respond and accuse Anna of rejecting the concept of polygamy that is allowed by the Holy Quran, she argues back and shows them a page from a classical book of hadith (sayings and deeds of the Prophet) that strengthens her argument.

Islam on the big screen

As a cinema phenomenon, the film has raised questions about the relationship between Islamic values and the film industry. Like other popular Islamic films that have preceded it, such as Ayat-Ayat Cinta, Kun Fayakun (Be, and It Is), Mengaku Rasul(Claiming to be a Prophet) and Syahadat Cinta (Testimonial of Love), Ketika Cinta Bertasbih is the result of a process of negotiation between idealism and commercialism. In the eyes of some film critics, the battle between these two objectives tends to result in a film genre that is mediocre at best. Other critics, like the film historian Salim Said, regard it as simply the latest illustration of an age-old and probably eternal struggle to reconcile the need for profits with the desire to produce quality films that benefit society.

There are Islamic groups and individuals who reject the whole undertaking. Lukman Hakim, a well-known Islamic blogger who belongs to the very conservative Salafi school, has written that buying a ticket to watch a movie like Ayat-Ayat Cinta is just like buying a ticket to hell. For him, watching movies is a useless and pointless activity that takes place in an environment of ikhtilat, meaning the mingling of boys and girls who are not blood relations in a non-segregated space. He sees cinema as a form of figurative painting, which should be forbidden according to Islamic law.

There are, however, various groups that try to combine cinema and Islamic law, such as MAV-NET (Morality Audio Visual Network) which has branches stretching from Padang to Bogor. MAV-NET has produced a manifesto which states that Muslim filmmakers should make movies that represent Muslim morality and do not violate Islamic law. Such groups try to find ways around problems that arise when attempting to reconcile every last detail of Islamic law and film culture. For example, a scene showing a husband and wife hugging can be a problem if the actors portraying the characters are not in fact married, because in reality these two individuals should not be in such close physical contact. Ustadz Abu Ridho from the PKS (Prosperous Justice Party) argues that in such cases if the focus is simply on Islamic virtues, then everything will be clear.

Other, more liberal, Muslim directors see things differently. Deddy Mizwar, for example, says that it is a filmmaker’s duty to expand the language of film in new and creative ways. Like a number of prominent Iranian directors, he believes that syariah (Islamic law) and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence) open up creative spaces in the search for alternative idioms and new forms of storytelling. For him, showing an unmarried couple hugging to express their feelings for each other is just an old-fashioned cinematic cliché. He goes for a more poetic alternative by having the male character in his popular TV series Para Pencari Tuhan (The God Seekers) address his female counterpart with the words, ‘If syariah allows it, I will purify myself in the water of your tears’.

Film critics and internet bloggers alike seem to agree that KCB is too wordy and too ideologically driven to be a successful work of art

What these conceptions of ‘Islamic film’ leave out of consideration is the question of how to place films with Islamic themes by prominent directors who are not proponents of the genre like Garin Nugroho or Riri Riza. Films like Rindu Kami padaMu (Our Longing for You) and Laskar Pelangi (Rainbow Militia) are not considered to be examples of ‘Islamic film’ but they are still full of Islamic values and representations of Muslim society. Film critics would argue that these films are more successful as art, and more representative of Islam in Indonesian society than the works of self-declared makers of ‘Islamic film’.

An artistic achievement?

In contrast, film critics and internet bloggers alike seem to agree that KCB is too wordy and too ideologically driven to be a successful work of art. Unlike films from other parts of the Islamic world, especially Iran, KCB largely ignores the language of film, preferring to present all its religious content through verbal explanations alone. For some viewers, it is just another sinetron, an open-ended soap opera like so many others on Indonesian television.

Yet the film’s promoters continue to insist on its ‘quality’ aspects. Advertisements have included statements by prominent Islamic figures such as Hidayat Nur Wahid, a founder of the PKS and chairperson of the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR), who stated that the commercial success of KCB proves that Indonesian cinema audiences have the ability to identify quality and value in film. The same advertisement that includes Hidayat’s endorsement urges potential viewers to show their support for quality Indonesian film by seeing the film: ‘By watching KCB you are contributing to the birth of a national cinema of quality, dignity and respect for women’ viewers are told. Some observers see this kind of promotion as a sign that the filmmakers are afraid their film will be seen as nothing more than a box office hit, and not the ‘authentically Islamic’ film they want it to be remembered as. ii

Ekky Imanjaya (eimanjaya@yahoo.com) is co-founder and editor of Rumahfilm.org , an Indonesian online film journal.

If you live in Melbourne Australia you may wish to book in to the Indonesian Film Festival 2009 (11-20 August) at www.indonesianfilmfestival.com.au/ . It includes Riri Riza's Laskar Pelangi.