Indonesia’s transgendered community is raising its profile.

Irfan Kortschak

Popular stereotype: the waria hair salon worker |

Before she even opens her mouth, the petite, jilbab-wearing and refined looking Shuniyya Ruhama Habiiballah has already gone a long way towards achieving one of her driving missions in life: to challenge the dominant stereotype of Indonesia’s large transgendered community, who describe themselves as waria, a term for transgendered people derived from the words wanita (woman) and pria (man).

As Shuniyya says in her softly spoken, decidedly feminine voice: ‘People see the waria as sex workers on the side of the streets at night, dressed in mini-skirts, with silicone-inflated breasts as large as watermelons. They see the show business drag queens who perform on stage and on television. They see these waria and think that they know what a waria is. They don’t. The waria they see are just the most obvious and easy to identify, and the ones the straight community are most likely to meet.’

Shuniyya is uncomfortable with many of the current definitions of the term ‘waria’, simply because these definitions are not sufficiently inclusive. For example, she disputes well-known gay activist Dede Oetomo’s definition of waria as men who imitate women in their clothing styles or mannerisms ‘while retaining a masculine identity’. She says that while this may be true for some, a significant proportion would strongly disagree that they consider themselves to be men.

‘The waria community is very diverse,’ Shuniyya declares. ‘It includes individuals who continue to identify as male but who imitate certain feminine mannerisms, and perhaps occasionally wear makeup and women’s clothing. Others identify so closely as female that they are able to pass as female in their daily interactions in society. As waria, these individuals become almost invisible.’

Shuniyya is strident in her dismissal of the stereotyped image of the waria as a flamboyant cross-dressing sex-worker living on the fringes of society. ‘Many waria come from middle class backgrounds and have a high level of educational attainment. Many hold respectable positions in established companies. There are waria who work as designers, psychologists and sociologists. The image that all waria are sex workers or employees of hair salons is simply a myth,’ she says. ‘In the end, only a waria knows what it means to be a waria. We have to define ourselves.’

|

Finalists ‘under quarantine’ in JakartaIrfan Kortschak |

However, Shuniyya does acknowledge that social prejudice and discrimination mean that waria often find themselves with limited work options. Very many work in the beauty and cosmetics, entertainment and fashion industries, or in the NGO sector, particularly in NGOs dealing with gender issues. Describing her own employment at a foundation dealing with transgender issues, she says: ‘Looking at me, no-one would guess that I’m not a woman.’ However that does not mean that she has a woman’s freedom to choose her field of employment.

This is because while her identity card (KTP) shows her to be female, other official documents like her birth certificate and academic transcript identify her as male. Legally, there is no precedent for a transgendered individual, including post-operative transsexuals, to alter the gender that that they are identified with at birth. Thus, when applying for almost any form of formal employment or going through any other formal process at which a full range of personal documentation is required, a waria cannot pass as female.

|

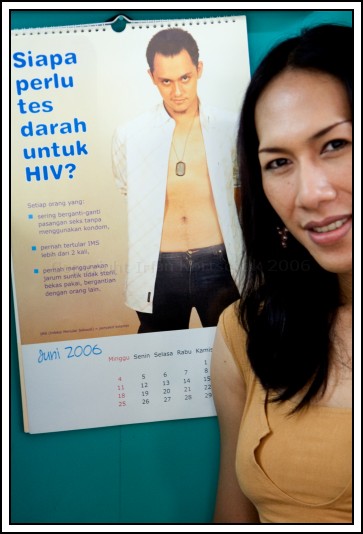

HIV/AIDS educationIrfan Kortschak |

Given social attitudes, this bureaucratic hitch is often a critical impediment to obtaining a job. It explains why Shuniyya’s examples of waria who hold respected professional positions seem to be the exceptions, rather than the rule. She seems reluctant to admit that in the face of this strong social prejudice, employment options are limited, and a significant proportion of waria do, in fact, at least occasionally engage in sex work.

The Miss Waria Indonesia pageant

Shuniyya herself is employed at the Yayasan Putri Waria Indonesia, an institute founded by former waria beauty queen Megie Megawatie to keep the Miss Waria Indonesia pageant running as an annual event. From these roots, it is now also involved in a range of other activities, including those related to sexual health education, employment creation, anti-discrimination, and advocacy.

In fact, according to the distinctly glamorous Megie Megawatie, the Miss Waria Indonesia pageant is itself a powerful means of achieving all of these aims. ‘First and foremost, the idea of the pageant is to challenge the stereotype of the waria, not only amongst the broader community, but amongst the waria community itself. We want to demonstrate to the public that we are capable of staging a spectacular, high-profile event in which waria can show the world that they have a diverse range of talents, skills and assets.’

‘We want to demonstrate that waria are an important, integral part of the Indonesian community,’ she says. ‘But perhaps even more importantly, we want to provide members of our own community who may not be secure in their identity with role models. We want them to know that they, too, can be accepted, valued members of society.’

A number of events staged at the pageant are clearly intended to demonstrate that the acceptance of waria into Indonesian society is part of established tradition. In 2006, performances by guest stars included a traditional performance by a troupe of bissu, the group of ritual specialists formerly attached to the royal houses of South Sulawesi, who are often described glibly as ‘transvestite priests’.

|

Co-opted waria?: bissu from South SulawesiIrfan Kortschak |

To include bissu in the group described as waria requires a quite extraordinarily inclusive and flexible interpretation of the term. As Sharyn Graham points out (Inside Indonesia No. 66, April-June 2001), while bissu do have certain effeminate mannerisms, they do not engage in cross-dressing, but have their own distinctive clothing. Furthermore, they are not men who identify as female. Rather, they see themselves as transcending gender, identifying neither as male or female, but as ‘a combination of all genders’. However, it is at least true that their existence challenges accepted gender stereotypes, and their association with one of the established high cultural traditions of one of Indonesia’s regions fulfils the purpose of their inclusion in the pageant.

The main event of the pageant, the selection of the year’s reigning Miss Waria, follows the pattern established by standard beauty pageants almost entirely, with the usual parades and talent quests. One finalist is chosen to represent each of Indonesia’s 30 provinces, by committees or representative organisations established in each of those provinces. These committees operate with a considerable degree of autonomy, although they conform loosely to standards established by the central organising committee.

As with the events on which it is modelled, at least at the level of rhetoric, equal importance is placed on appearance, achievement, performance skills and moral standards. Moral standards are included because, in the organisation’s view, Miss Waria Indonesia is to be a role model for the whole community. In particular, in order to eligible for the title, finalists must enter into a contract that, amongst other matters, explicitly forbids them from engaging in sex work while they hold the title.

|

In the dressing roomIrfan Kortschak |

Tacit acknowledgement

While the organisers of the Miss Waria Indonesia event appear to be at pains to distance the pageant and its participants from association with the negative stereotype of waria, there is at least some tacit acknowledgement that the behaviours associated with the stereotype do continue to characterise the waria community.

On arrival in Jakarta, all finalists are placed under quarantine in special quarters for three days. During this time they are given training, lessons and examinations on issues such as HIV/AIDS prevention, sexual health and illegal drug use and its impact – all of which are of particular importance, of course, to those waria engaged in sex work – as well as more traditional areas of interest such as fashion, cosmetics, and appearance. In 2006, the specified role of the crowned Miss Waria was to act as spokesperson on two rather divergent issues: tourism and HIV/AIDS.

It might perhaps be argued that rather than trying to hide the association between waria and sex work, a more positive approach would be to challenge the prevailing code that denigrates waria sex workers. Also, it is clear that despite Shuniyya’s comments about the diverse and inclusive nature of the waria community, it is only those waria who most clearly fit the traditional stereotypes of female beauty and talent that are considered for selection. Viewing the finalists, the resemblance to the participants of the traditional Miss Indonesia pageant is almost eerie. The event is no caricature of traditional beauty pageants: it resembles them completely.

However, as Megie Megawatie sees it, the goal of the pageant is not to help bring about a fundamental shift in Indonesian moral values and standards of beauty. Rather, it is to win acceptance for the waria community by showing that waria can conform to these values. And while the waria community itself is divided into many factions, with some considerable rivalries and jealousies between them, there does appear to be at least a grudging acknowledgement that this approach has been beneficial. Even those whose own behaviour and appearance would make them unacceptable as participants themselves seem to agree that the approach has raised the community’s profile and increased its acceptance as a whole.

|

Merlyn Sopjan, Miss Waria Indonesia 2006Irfan Kortschak |

Friends and enemies

At the very least, by striving to make the waria community respectable, Megawatie’s attitude has won a considerable degree of acceptance from Indonesian officialdom for the pageant – although it has also attracted moral condemnation from less tolerant members of society.

These less tolerant reactions have included, predictably enough, those of the Islamic Defenders Front (FPI). In 2005, when the event was staged at the Sarinah Building and attended by a number of public figures, including serving governor Sutiyoso, Indonesia’s most notorious gang of gate-crashers also put in an appearance. Approximately 100 members of FPI staged a noisy entrance, demanding that the event be disbanded.

In the face of a heavy police presence, representatives of FPI were encouraged to engage in a dialogue with several of the event’s organisers. Perhaps disappointed that the event did not reach the hoped-for levels of moral depravity or, perhaps more likely, intimidated by the police presence, the FPI group was finally persuaded to leave peacefully. With just a hint of sarcasm, Megie Megawatie says, ‘Perhaps we should be thankful to them. They raised the profile of our event dramatically.’

The raised profile of the event in the following year was demonstrated by the attendance of an even greater array of notables, including former president Abdurrahman Wahid, who may well have appeared as a direct response to the previous year’s disruption. At the event, he gave a long, rambling, almost completely incomprehensible speech, to which almost no-one listened. Of course, it didn’t matter: the important thing was that he came.

However, Megie Megawatie claims that the former president has played an important and helpful role in assisting the community, above and beyond his attendance at the 2006 event. It was at his suggestion, she says, that the Yayasan Putri Waria Indonesia was established as a permanent organisation, rather than, as previously, as a periodic committee whose sole purpose was to manage the Miss Waria event.

|

‘Senior patrons’: older waria at the pageantIrfan Kortschak |

|

Megie Megawatie, founder of Yayasan Putri Waria Indonesia, and friendIrfan Kortsc |

As Megie Megawatie states, the foundation’s association with the pageant has made it one of the most high-profile and accepted of all of the many organisations and NGOs claiming to represent the interests of the waria community. As the organisation develops, she says, the acceptance of the broader community for the event will play a vital role in raising funds and gaining acceptance for organisation’s planned educational, advocacy, and health awareness programs. Playing by society’s rules, it seems, rather than confronting its values, has been a recipe for success. ii

Irfan Kortschak (irfan@wayang.net) is a long-term resident of Jakarta. He is currently engaged in writing assignments and consultancy work for NGOs and development agencies in Indonesia.