A portrayal of village life suggests alternate model of piety in Aceh

Daniel Birchok

Legal reforms in the Indonesian province of Aceh over the last decade have emphasised the importance of highly visible Islamic objects and practices for transforming the province into a more properly Islamic society. These range from the adoption and legal enforcement of dress codes to strict laws governing the practice of the fasting month and architectural styles of newly constructed government buildings that resemble those used in the building of mosques. In general, these public displays of piety have been widely embraced. Large numbers of men and women have chosen to alter their comportment or clothing styles, assist raids by vice police or neighbourhood vigilante groups patrolling public morality or have committed themselves to the building of an ever increasing number of village mosques.

But Acehnese also have alternate ways to understand Islam’s proper place in their society.

Aceh’s thousands of neighbourhood coffee houses serve as dominant centres of male sociability. They frequently have television sets and feature an entertainment line-up of Indonesian soap operas, feature films from Hollywood and Bollywood and international football matches.

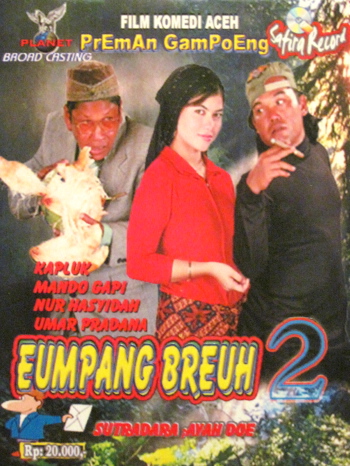

One of the most popular programs in recent years, both in these shops and among private viewers at home, has been the comedy, Eumpang Breuh (Rice Basket), which focuses on Acehnese village life. For the crowds of men who patronise the coffee houses, watching Eumpang Breuh offers an opportunity to comment on issues related to Islam, gender and the village. Their commentaries on the film reveal different imaginings of a properly Islamic Aceh.

Romeo, Juliet and Three Stooges

Since the creation and circulation of the series’ first episode in 2006, Eumpang Breuh has become an Acehnese cultural phenomenon. Never produced for broadcast, each episode has been individually created and released on video compact disc, all seven of which remain available for purchase. The series’ actors are celebrities and among the most recognisable figures in the province, along with government office holders, popular Islamic teachers and former Acehnese independence fighters. On two occasions the cast has partnered with international non-governmental organisations to produce special episodes related to issues of post-tsunami and post-conflict social and economic development.

The story’s narrative revolves around an unemployed village tough called Bang Joni and the village beauty, Yusniar. At the beginning of the first instalment, Yusniar’s father, Haji Umar, forbids her to return to the city of Medan, just across the border in North Sumatra, where she has recently attended university. She is clearly disappointed, but obediently remains in the village with her father and mother. Shortly thereafter Yusniar falls into the river while doing chores, only to be rescued by Bang Joni and his sidekick Mando. Taken by her beauty, Bang Joni falls for Yusniar and sets about – over the rest of the seven episodes – to win her heart. This entails a seemingly endless stream of slapstick adventures in which our hero is routinely attacked by the quick-to-anger Haji Umar, who has other plans for his daughter, and fends off numerous other suitors through trickery and the mobilisation of a network of friendly neighbourhood thugs. The result resembles an Acehnese mash-up of Romeo and Juliet and The Three Stooges.

Equally as important as the plot – if not more so – are the character-types represented by each of the main roles. Much of the humour revolves around the skilful portrayal of typical character traits by the actors. Viewers gleefully anticipate Haji Umar’s angry tirades or moments in which Bang Joni stumbles unknowingly into a lucky set of circumstances, both recurring scenes that are thought to reveal fundamental aspects of each character. It is these traits that many viewers of Eumpang Breuh identify as the primary means through which the series effectively portrays village life.

The playing of each of these characters is skilfully combined with devices such as word play, cases of mistaken identity and slapstick to produce the show’s comedic effects. In the first episode, for example, Bang Joni playfully impersonates a village mystic when he is approached by Yusniar seeking romantic advice. He is able to use this instance of mistaken identity to suggest to her that of her many suitors, it is only one whose name begins with a J (for Joni) who is her match. Like scenarios in later episodes, this scene simultaneously advances the plot, reveals something of Bang Joni’s fortuitous nature and gets viewers laughing.

Islam and gender through Acehnese comedy

If Eumpang Breuh is a mirror of an Acehnese village, it is one shaped by the imperatives of its comedic genre. The series exaggerates particular features of the stereotypical village. With the exception of Yusniar and one of her most persistent suitors, a Batak man named Sitompul, whom she knows from her time in Medan, all of the main characters have horizons that fall well within the geographic and cultural boundaries of rural Aceh. This is even largely true of Haji Umar, who has been to Mecca, but whose daily concerns and outlook are resolutely local. Tropes of rural backwardness – ranging from engagement in certain kinds of mystical practices to the inability to properly understand sophisticated, Indonesian neologisms – are repeatedly exploited for humour. In the late night and early morning hours over coffee, urban and rural viewers howl knowingly with delight at these caricatures of Acehnese country bumpkins. But they also see redeeming qualities of the characters.

Viewers unanimously disagree with the proposition that Eumpang Breuh is an Islamic film, a specific and often pedantic genre that has enjoyed considerable popularity in Indonesia in recent years. Compared to nationally-produced films that are explicitly Islamic and marketed as such, Eumpang Breuh contains relatively few unambiguous Islamic markers. On occasion Bang Joni is filmed in prayer. However, his prayers sometimes are questionably motivated and often a touch mischievous, such as in the sixth episode when he asks God to give him ‘more than other people have’. Yusniar covers her hair, but in a fashion that many in Aceh would agree was less modest than behoves a young, unmarried woman. Haji Umar is by far the most identifiably Muslim character. He wears a peci (a type of cap) that signals his status as a returned pilgrim and regularly offers contextually relevant quotations from the Qur’an. But even Haji Umar does not approach the number or intensity of more outward displays of Islamic identity and practice found in portrayals of characters from more explicitly Islamic films – or, indeed, in the Acehnese public sphere.

|

It is perhaps not surprising that, as a comedy, Eumpang Breuh rarely valorises the usual symbols of Islamic revival found in explicitly Islamic Indonesian films. Many of these symbols – kinds of dress, patterns of consumption, approaches to sacred language and text – are generally understood by Acehnese as more properly urban than rural, even though in practice these categories are blurred by large numbers of people who spend portions of their daily lives deeply enmeshed in both urban and rural settings. Nonetheless, many viewers insist that Eumpang Breuh, while not by genre an Islamic film, contains central themes that are consistent with a proper Islamic life.

One plot point frequently cited as illustrating the series’ Islamic themes occurs in the second episode, when Haji Umar falls into a well and makes a kaoi, or promise to God or a deceased holy person. Haji Umar promises that whoever rescues him will receive the hand of Yusniar in marriage. Shortly thereafter, Bang Joni comes along and successfully rescues his beloved’s father, an act illustrating Bang Joni’s good nature and fortuitous timing, both taken to be among his Islamic qualities. For many viewers, Bang Joni’s rescuing of Haji Umar sealed everyone’s fate. Haji Umar may be quick to anger, but he is a good Muslim. There is no way for him to go back on this kaoi. Bang Joni will have Yusniar’s hand in marriage. It is simply a matter of time. The film’s producers, however, have thus far done their best to defer this much-anticipated tying of loose ends.

The ways in which Haji Umar and Bang Joni reflect an Islamic – and Acehnese – set of character traits redeems them from their rural backwardness. This both reinforces and is reinforced by wider ideas that represent the village as the ultimate site of authentic Acehnese identity. This argument should not be overdrawn, as Eumpang Breuh is, after all, a comedy relying on humour that pokes fun at the rural sensibilities of its characters. Yet both rural and urban viewers articulated respect for Bang Joni and Haji Umar as figures of Islamic piety.

They said similar things about Yusniar, although her position is more conflicted. Yusniar is overwhelmingly and enthusiastically praised for her polite mannerisms and obedience to her parents. Viewers explicitly identify these characteristics as Islamic and many believe that they outweigh any flaws one might perceive in the modesty of Yusniar’s dress. For many women, and some men, Yusniar is the central character, who brings all of the male characters in the story together. Some even admire her ability to manipulate social situations using the tools proper to her position as an Acehnese village woman with some education. But many young men express distrust of Yusniar. One noted, ‘There is no question that Bang Joni loves Yusniar. But Yusniar, her love is not certain.’

Those men who are themselves unmarried almost unanimously admit that they would wed someone like Yusniar. But even college educated men with real, if uncertain, potential for upward economic and social mobility find such a match out of the realm of possibility, and express reservations about Yusniar’s relationship with Bang Joni. Beautiful, well-educated, polite, obedient and clever, she is the perfect catch. But here lies the rub. How could she possibly be in love with the unemployed, physically and socially clumsy – and opportunistic – local thug who is, at best, of average intelligence? Yusniar’s double-bind is not unusual for young, educated Acehnese women. Her beauty and education make her highly desirable as a marriage partner. But these same factors, and the mobility that has come with them, are sources of distrust.

Yusniar’s suitors include the son of a man who travelled to Mecca with her father, a Batak man she knew in Medan claiming to be her boyfriend, and numerous others. They regularly visit her, and a few of the less refined among them actually harass her on occasion. Bang Joni’s repeated need to violently turn away Yusniar’s other suitors, in particular the Batak Sitompul, resonates with common concerns regarding the sexual desirability of female college students, and associated fears of their potential promiscuity. In Aceh such concerns are regularly voiced in press reports, sermons by religious teachers and in everyday conversations, marking such women as a vulnerable yet also dangerous group in need of both protection and surveillance. As an educated woman, Yusniar’s position vis-à-vis Bang Joni may be the source of laughter. But it is also creates tension for the audience. Despite her professions to the contrary, how could she possibly choose Bang Joni?

An alternate imagining

So what can be learned from a few evenings watching Eumpang Breuh in an Acehnese coffee house? For a large portion of the series’ viewers, Eumpang Breuh portrays Acehnese village life in double-take, amiably poking fun at rural folk while at the same time validating them as authentically Acehnese and, ultimately, Muslim. In doing so it articulates a sense that everyday village life is deeply compatible with Islamic principles in ways that do not require an abundance of visual markers of Islamic identity. The film may never be identified as falling within the Islamic film genre, the cinematic analogue to the stress placed on these objects and practices in the public sphere. Yet viewers consistently and emphatically point to Islamic themes in the identifying characteristics of the major characters and in the primary turning points in plot. It is clear that viewers take these characters and their interplay through the plot very seriously, even as they laugh at them.

It is important not to assume that Eumpang Breuh enthusiasts are against public displays of Islamic practice because they also find compelling the more subtle examples of piety found in the comedy. Coffee shop viewers are firm that the two models are simply two different instances of being properly Islamic. However, it is difficult to deny the way in which the series might represent an alternate imagining of Muslim society in Aceh. This imagining shifts focus to the distinctly Islamic qualities of stereotypical village characters whose Islamic traits might otherwise remain hidden underneath a rural lack of refinement.

The predominantly young, male viewers enjoying the series over coffee on any given evening see the series in terms of devotion to family, the economic and social customs of the village, anxiety over gender roles and the ability to find a trustworthy marriage partner – all things they identify as explicitly Islamic concerns. They find in the series a response to these concerns through representations of Islamic sensibilities arising from authentic, if at times comically wild, Acehnese village experiences. This by no means contradicts an affinity to public displays of Islam and Islamic practice. But it does momentarily de-emphasise them in favour of character traits believed to inhere subtly in Acehnese rural folk.

Daniel Birchok (dbirchok@umich.edu) is a PhD candidate in Anthropology and History at the University of Michigan.