Taring Padi takes stock of a more than a decade fighting the political establishment – with art as its weapon

Anett Keller

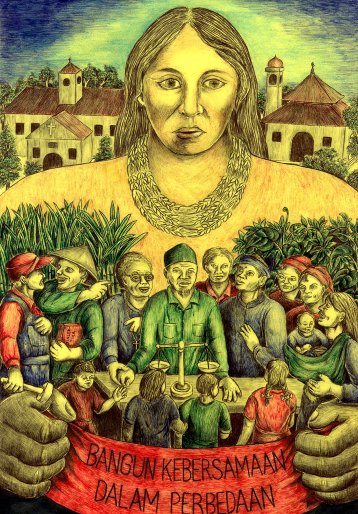

Build unity amidst differenceTaring Padi |

May 2010: on the tiled floor of an empty house in Porong, Sidoarjo, several neatly dressed men sit in a semicircle, sipping glasses of tea. Before them sits a small group of younger long-haired men and women, some tattooed from head to toe. Initially, it looks as if both sides come from different worlds, but it quickly becomes clear that they share a common concern. The older men are village heads, and they represent communities affected by a mud volcano that displaced tens of thousands of villagers in the Sidoarjo area of East Java since 2006. Their villages are devastated; their livelihoods and health are threatened. Everyone here calls it the ‘mud of Lapindo’, after the company whose boreholes scientists say caused the disaster (see Bosman Batubara’s take on this disaster recently in Inside Indonesia).

The tattooed people are artists, and part of the art collective Taring Padi. They came from Yogyakarta to Porong to help the victims of the mud volcano fight for their rights. Many people here are still waiting for compensation for their destroyed homes. Many still suffer poor health as a consequence. There is no end to the disaster in sight.

For one week, the Taring Padi artists helped people around the volcano to make their voices heard and their concerns visible. In woodcut printing workshops, they worked with villagers to produce plates for printing T-shirts and create posters and banners. They also sang and created songs with local children. Finally, on the fourth anniversary of the eruption of the mud volcano, the activities culminated in a long march and a late-night concert (see coverage at EngageMedia).

The initiative helped to revive hope, solidarity and the spirit of resistance among a group of highly marginalised people who feel forgotten by the leaders of their country and by the rest of the world. It was a typical Taring Padi program.

A record of solidarity

Numerous events like this one are now documented in the richly illustrated book Seni Membongkar Tirani (Art Smashing Tyranny). In the book, released in August 2011, Taring Padi looks back at more than a decade of work.

This bilingual (English and Indonesian) chronicle of artistic resistance is encased in an elaborate woodcut print and published in an edition of 1,000 copies. Its 338 pages with hundreds of images of works produced by Taring Padi members are a journey through time. It tells how a group of art students and activists became an important part of the Indonesian contemporary art scene. And it depicts a journey through the most recent history of the country, which is now often celebrated as being the third largest democracy in the world.

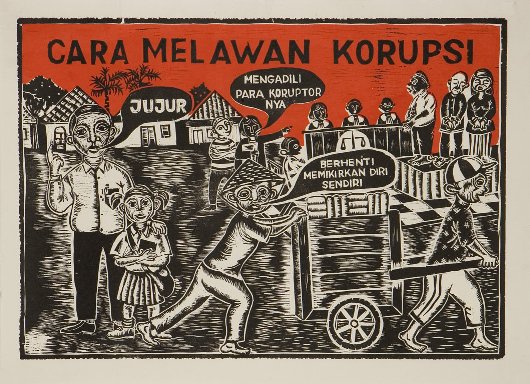

The works of Taring Padi, however, offer no songs of praise: not about Indonesia, nor about the rest of the world. Taring Padi’s creations instead place special emphasis on those whose hopes for justice are still unfulfilled: poor farmers or factory workers, the politically disenfranchised and those affected by environmental destruction. They denounce corruption, exploitation of natural resources, social inequality and violence.

The volume provides an inspiring overview of the work of the collective. As well as including many illustrations of their artwork, it includes 13 essays, covering issues such as antimilitarism, environmentalism and gender, reflecting on the breadth of Taring Padi’s concerns.

|

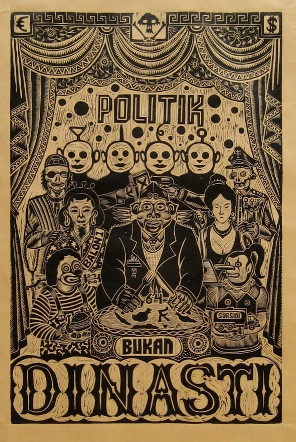

Politics is not a dynastyTaring Padi |

On December 21 in the turbulent year 1998, a group of (mostly art) students met at the office of the Legal Aid Organisation (LBH) in Yogyakarta. There they declared the foundation of Lembaga Budaya Kerakyatan Taring Padi (Institute of People Oriented Culture: Taring Padi). An illustration on page 16 of the book portrays the aim of the artists’ works. It shows a man holding a banner that says: ‘Good art is art that serves the people. And that is easily understood by them.’

One unique feature of Taring Padi’s works is that they are collective in origin. Either members of the group work on huge banners or billboards, which are used for demonstrations or to be displayed in public places. Or the members produce individual works on particular topics but then present them to the public during a joint event.

The group does not restrict itself to visual arts alone. Music is an essential part of its expression too, as Composer Jeffar Lumban Gaol reflects in his essay: ‘Taring Padi’s music as a tool for generating awareness’. Members of Taring Padi and the band Dendang Kampungan (consisting mainly of Taring Padi members) are ‘acutely aware of the importance of lyrics in songs that can support cultural movements, either for themselves or for the public at large’, as Gaol puts it.

The Dendang Kampungan song Revolusi Budaya Memanggil Kita (Cultural Revolution Calls to Us) starts with the words: Rise, cultural workers/Move along with the oppressed/Welcome the bright red dawn/Unite, unite all. And it proceeds as a sort of Taring Padi manifesto: Destroy false cultural values/Establish new cultural order/Listen to the peoples’ demands/Follow the call of history/Work hard, create well/Wield your pen, use your brush/Let people know….

Taring in Indonesian means canine tooth. Taring Padi is the term used for the sharp tip of the rice plant. The name says it all: rice is essential to Indonesians but the tips of the plant can scratch and cause people to itchy. Contemplating Taring Padi’s art and its underlying message is meant to be uncomfortable. Sometimes it can be painful and difficult to endure. The collective touches upon many of the country’s unhealed wounds: unresolved human rights violations during the Suharto era like mass murder, forced disappearances, and arbitrary arrests; ongoing social injustice; militarisation; brutal exploitation of environmental and human resources. Not everyone sees these depictions of reality as a nice way to decorate the wall behind the couch.

|

How to fight corruptionTaring Padi |

Not for art’s sake

Art for art’s sake never interested the activists of Taring Padi. ‘Not for the sake of fine art discourse’ reads the title of one essay, where the famous Indonesian sculptor Dolorosa Sinaga describes the work of Taring Padi. Dolorosa compares the collective with the legendary movement of the Dadaists in Europe because of their common anarchist view of the world and their goal of deconstructing the values of those in power, as well as the notions of beauty based on those values.

Fellow painter and illustrator Yayak Yatmaka reflects upon stylistic similarities between the work of Taring Padi and the socialist realism that came out of the Soviet bloc in the early and mid twentieth century. But while socialist realism was state sponsored art, Taring Padi is its antithesis: an expression of opposition to the powers that be.

But in general, the essays deal little with stylistic details in the work of Taring Padi. Instead, the authors focus on the intentions and contexts underlying the work of Taring Padi. In other words, they look at the social circumstances that are – as when the German playwright Berthold Brecht used the term in his famous ‘Threepenny Opera’ – so unsatisfying that artists can no longer waste their time creating art for aesthetic purposes only. Taring Padi’s actions often bring the artists together with the victims of these social circumstances, and work collaboratively with them to convey their own messages in artistic media, including woodcut, printing, paint and music.

Mirroring the social circumstances of our times, the works of Taring Padi often look bleak. Nevertheless they do not radiate hopelessness. Instead they convey a defiant message: Together we are strong! How the artist collective Taring Padi lived and worked during the last decade and how it continues to do this is the best proof.

Taring Padi – Seni Membongkar Tirani (Art Smashing Tyranny), Yogyakarta: Lumbung Press, 2011 is available from lumbungpress@gmail.com.

Anett Keller (anettkeller@ymail.com) is a German journalist and researcher based in Indonesia. She has studied journalism, political science and Indonesian language at the University of Leipzig and at Gadjah Mada University in Yogyakarta.