While it’s tragic that some candidates kill themselves after Indonesian elections, at least they aren’t killing each other

Michael Buehler

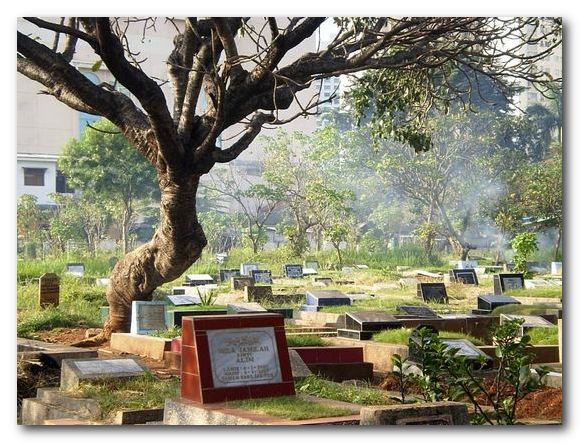

Sri Hayati was found dead outside the village of Bangunjaya in West Java at 7.30 on the morning of 15 April 2009. Using her headscarf, she had hung herself on a pole in a hut in a rice field. The 24 year old woman had been running for a seat in the parliament of Banjar City for the National Awakening Party but had gathered only ten votes in the general legislative elections that were conducted on 9 April. According to the local media, Hayati, who was four months pregnant, committed suicide due to this dismal result.

In the town of Takalar, South Sulawesi, Saribulan Daeng Singara, a 56 year old housewife, slit her wrist with a razor in her bathroom on 28 April 2009. Again, a failed candidacy for the local parliament had apparently triggered her suicide. After racking up massive debts to finance her political campaign in the elections, Singara saw no other way out, so said the local press.

These were by no means isolated incidents. In the days immediately following the legislative elections, suicides and suicide attempts by political candidates were reported from several places across the far-flung Indonesian archipelago, including the city of Pontianak in West Kalimantan and Kupang in East Nusa Tenggara.

No election-related killings

The reports about the suicides of legislative candidates around the time of the elections contrast with a complete absence of stories about politically-motivated killings during the same period. While there were the occasional articles about electoral violence, usually in the form of voter intimidation, there were no reports whatsoever of candidates killing each other in the competition for seats in the national parliament or sub-national assemblies.

There were no reports whatsoever of candidates killing each other in the competition for seats in the national parliament or sub-national assemblies

This is in stark contrast to other democracies in Southeast Asia. In the 2007 elections in the Philippines, 37 candidates were killed and 24 were wounded, a slight improvement compared to the 2004 elections during which 40 candidates were murdered and 18 candidates were injured, according to data from the Philippine election commission. In addition, 121 people who were not candidates but canvassers, campaign managers or voters were killed in 2007, and 148 were killed in 2004.

Election-related killings of parliamentary candidates are also common in Thailand. Politically-motivated murders amongst candidates became so widespread in the 1980s that some commentators regarded them as an indication of consolidation of the Thai electoral system. Benedict Anderson famously argued in a 1990 article (‘Murder and progress in modern Siam’) that such murders were a sign that national parliament had become a site where power was concentrated, making it worth one’s while for ambitious local political bosses to murder their rivals. More than a dozen political killings were reported in the 2005 elections in Thailand.

The absence of political murders in Indonesian elections is remarkable inasmuch as many of the conditions that are believed to play a role in election-related killings amongst candidates in other Southeast Asian countries – such as weak election commissions, the prevalence of private security organisations and thugs in the political system and the absence of programmatic politics – can be found in Indonesia too.

Why don’t aspiring politicians murder each other in Indonesia? Both institutional and sociological factors play a role. A number of aspects of the institutional design of Indonesia’s new democracy at the local level dampen the winner-take-all dynamic that motivates political killings elsewhere. The absence of a tradition of feuding between oligarchic clans and the political dominance of bureaucrats at the local level have the same effect.

Not worth the trouble?

If we assume that murders of political opponents result from intense competition for highly valued positions, it makes sense that political systems that either lessen the intensity of competition or reduce the value of the prizes will reduce the incentives to kill.

One way to reduce the incentive to kill is to increase the number of political prizes available for each pool of candidates. Despite the increase in the number of electoral districts for the 2009 general election from 69 to 77, the number of electoral districts in Indonesia is still relatively low compared to Thailand with 174 districts or the Philippines, which now has 220 electoral districts. This means that in Indonesia, on average three to ten parliamentary seats are up for grabs per electoral district in legislative elections. In Thailand, the number drops to one to three seats per district. In the Philippines, there is only one seat allocated per electoral district. In short, more seats can be won in Indonesia per election district. Presumably this plays a part in lowering the incentive for candidates to resort to drastic measures such as killing a political opponent, because they believe they have a reasonable chance of winning at least one of the seats on offer.

The civil service background of most Indonesian candidates for executive positions greatly reduces the probability of political murder

It is also possible to argue that seats at both the national parliament and sub-national level do not come with enough powers – and hence, money-making potential – to make them worth killing for. The Regional Governance Law No 32/2004 stripped local parliaments of their rights to impeach district heads, appoint regional secretaries and screen election candidates for executive posts. Various other regulations of past years have shifted power from the legislative to the executive at the national level too and this trend seems to continue. For example, the State Secrecy Bill, should it be adopted in its current form, might deprive the national parliament of its right to investigate any violation allegedly involving the executive government and its officials.

But by the same token, elections for local executive government positions in Indonesia should be bloody affairs. Elections for the key local government positions, notably of district heads (bupati in rural areas, mayors in urban municipalities) operate on a winner-take-all basis. Moreover, the spoils of office are also greater. Already empowered by Indonesia’s post-Suharto decentralisation policies, the Regional Governance Law No 32/2004 increased the power of the district heads even more with regard to matters like appointment procedures for crucial positions in the local bureaucracy. It also gave them greater fiscal powers, for example the power to authorise expenditure and set priorities and ceilings in local budgets. District heads also issue local regulations and taxes in cooperation with local parliaments. As many studies of local government in post-Suharto Indonesia have revealed, such far-reaching responsibilities also open up all kinds of opportunities for self-enrichment.

Surely these powers and potentials make district head posts worth killing for? Yet here again Indonesia confounds the wider Southeast Asian trend. Direct elections for such positions have been largely peaceful ever since they were introduced in 2005.

Again, there are institutional reasons for why this is the case. For instance, the time a district head can spend in office in Indonesia is capped. A district head can only serve two terms in his or her entire life anywhere in the archipelago, each term lasting five years. While there are various districts where out-going heads have tried to replace themselves with their offspring, overall it is much more difficult for Indonesian local elites to entrench themselves in sub-national executive positions than it is in other Southeast Asian countries. In the Philippines, for example, a regent can occupy his post for three consecutive three year terms, get his wife elected for a term, and then run for another three consecutive terms, get his wife elected for a term, setting in train a virtually never-ending cycle that can be passed on to the next generation. The institutional setting in Indonesia results in a more open and fluid system that makes political killings less likely. Political hopefuls have the possibility to gain office by just sitting it out, rather than by trying to break an incumbent’s dominance by murder.

Indonesia’s local elites prefer to share out the spoils of government rather than kill each other for them

Another reason might be that the fragmentation of Indonesia’s administrative structure has enlarged the number of lucrative posts available for competition. Between 1998 and 2009, Indonesian political elites increased the number of districts in the country from 230 to 510. This had the immediate effect of providing more district head positions and local assembly seats for ambitious local politicians. Indeed, there were many cases where candidates who were unsuccessful in election campaigns to become heads of larger districts would then lead lobbying campaigns to split off a smaller district and, when successful on that score, become its head.

More generally, elites in these districts have also gone about creating bloated local state apparatuses. The Regional Governance Law No 32/2004, for example, incorporated the wage bill of local bureaucracies in the formula for calculating how much money is transferred from the national level to sub-national administrative units. The larger the local bureaucracy, the more money the district or municipality concerned will receive from the central government. Receiving more money from the central government, local politicians have greater opportunities to provide jobs, favours and handouts to local elites, including potential rivals. Such structural incentives for rent-seeking thus have the positive impact of easing the competitive pressures on local elites. Basically, there is enough money and opportunities sloshing around in the system to at least partially satisfy everybody who is influential at the local level. Indonesia’s local elites prefer to share out the spoils of government rather than kill each other for them.

Economic factors have reinforced this dynamic. Socio-economic conditions over recent years in Indonesia have lessened the ferocity of elite competition by enlarging the pie of government funds that can be spread around. As the World Bank’s Public Expenditure Review from 2007 shows, Indonesian government spending has risen continuously since the year 2000. Aggregate expenditure increased by 20 per cent and transfers to sub-national governments grew by 32 per cent since 2006 alone, mainly due to the government’s reduction of fuel subsidies that opened up space for additional spending. These favourable conditions are likely going to continue in the immediate future. Despite a global economic downturn, Indonesia’s economy has been doing rather well. Indonesia’s budget will rise from Rp 1,000 trillion in 2009 to about Rp 1,800 trillion in 2014. A large chunk of this money will be pumped into the expansion of the government apparatus. Between 2010 and 2014 an estimated Rp 2000 trillion will be used up for government administration alone. In short, the money passing through the state apparatus is continually enlarging, providing sufficient opportunities for large parts of the political elite to benefit from it in a myriad of formal and informal ways, and thereby easing pressure on political competition.

Local traditions and weak thugs

The strongest explanations for Indonesia’s relatively peaceful electoral scene are sociological. There is no tradition of long-standing family feuds between oligarchic clans in Indonesia unlike in other Southeast Asian countries, where such dynamics explain a great many political killings. As authors like John Sidel have argued, the highly centralised state apparatus of the New Order regime under the dictatorial leadership of Suharto prevented local strongmen from emerging.

Clans and families in Indonesia have become more openly competitive since Suharto’s downfall in 1998. They have resorted to tactics that were unimaginable during the New Order. In 2007, for example, Amin Syam, then governor of South Sulawesi, tried to pressure his main competitor Syahrul Yasin Limpo into aborting his bid for the governorship by leaking a pornographic home movie, which featured the latter prominently. The unwitting movie star was voted into office nevertheless, perhaps expressing the hopes of the electorate that his performance in government would be better than what they had seen in the movie. However, bitterly antagonistic relations between dynasties that can turn elections into a season of vengeance in the Philippines (and to a lesser extent in Thailand) do not yet exist in Indonesia.

Despite the analysis of some commentators, the role of parastatal security forces and thugs in Indonesian political contests is marginal

Moreover, despite the analysis of some commentators, the role of parastatal security forces and thugs in Indonesian political contests is marginal. Professional doomsters like Vedi Hadiz, of the National University of Singapore, have told us that ‘shadowy gangsters and thugs are on the rise’ and that ‘beatings…the use of paramilitary organizations and…bomb threats were pervasive’ during elections in Indonesia. These quotations are from an article written by Hadiz in a 2003 edition of The Pacific Review, in which he also warned of a ‘democracy driven by thuggery’ that was characterised by ‘political violence, vote buying and kidnappings’ recalling ‘some of the experience of countries like Thailand and the Philippines’.

In fact, though Hadiz writes about the importance of gangsters and violence in Indonesian politics in general terms, most of his research focused on North Sumatra province, where gangsterism in politics traditionally looms large. But even the influence of thugs and the role of violence in North Sumatra’s politics are often exaggerated. There were no political murders in the gangster-infested capital of the province, Medan, during the 1999, 2004 or 2009 elections. True, gangsters have managed to win a few political positions in elections there. Three well known gangsters, Bangkit Sitepu, Moses Tambunan and Martius Latuperissa were elected to the local assembly in the city of Medan in 1999 (each representing different parties). Once in parliament, however, such figures behaved no more violently or corruptly than the average Indonesian parliamentarian. And in most provinces, they hardly feature as prominent political players anyway.

The politically influential ‘big boss’ Olo Panggabean in Medan died peacefully in his bed as a result of complications from diabetes at the age of 68

Moreover, gangster figures, should they find their way into politics, have been unable to escape the new democratic dynamics. While the official results of the legislative elections in Medan in 2009 were not out at the time of writing, it seems that of the three, only Bangkit Sitepu managed to get re-elected in 2009. Of the 50 parliamentarians in the assembly, 39 are new faces. What is most interesting is that in Indonesia even political gangsters seem to accept the election results. Indonesian thugs do not go on killing-sprees even if voted out of office, as is shown by the absence of politically-motivated murders in Medan. The manner of death of politically influential ‘big boss’ Olo Panggabean in Medan a fortnight after the elections is telling. On 30 April 2009, this capo di tutti capi died peacefully in his bed as a result of complications from diabetes at the age of 68.

Bureaucrats as bosses

Probably most important of all in explaining why there is so little violence against electoral candidates is the nature of the candidate pool in Indonesia, which differs markedly from pools in other Southeast Asian countries. In Indonesia it is mostly bureaucrats who compete for district head posts while in the Philippines it is families rooted in landownership or career politicians. In Thailand, at the height of political killings, most competitors for political posts were part of an extra-bureaucratic bourgeoisie consisting of merchants and members of the trading communities in the country’s big cities.

The civil service background of most Indonesian candidates for executive positions greatly reduces the probability of political murder. If a bureaucrat is running in local executive elections, the legal context in Indonesia dictates that such a candidate has to step down from his or her current position as a state official (jabatan). However, he or she remains a member of the bureaucratic apparatus (pegawai negeri sipil), and so retains insurance benefits, access to pension funds and, most importantly, has the opportunity for a future job in the bureaucratic apparatus if he or she fails in the election. A bureaucratic career is a comforting safety net for would-be government heads, creating much less of a winner-takes-all dynamic than one finds in the Philippines or Thailand where businessmen or landlord candidates don’t have bureaucratic careers to fall back on, and where failure might spell financial ruin. As the implications for a failed candidacy are less severe in Indonesia, candidates have less incentive to rely on risky and brutal methods.

Suicides

For whom then do elections in Indonesia turn into a deadly event? There were cases reported from Bali, Semarang and South Aceh of male candidates dying from heart attacks after they were presented with their poor election results. Anecdotal evidence suggests, however, that suicides occur predominantly among women candidates. Put on party lists simply to fulfil the requirement in the election law which says that every third ranking on a party list has to go to a female candidate (the so-called zipper system), many of these women were inexperienced and did not know what to expect when they entered politics. Commenting on Sri Hanyati’s death, the local ward boss of the National Awakening Party, Zaenal Muttaqien simply said: ‘Sri was only a sympathiser of [the party]. She was neither a party functionary nor a member of the party board. Initially, we...just suggested to her that she become a candidate to fulfil our quota of female candidates’. Unfortunately, such women often become heavily indebted in order to finance their election campaigns. When they see their poor results, they not only feel humiliated, they also realise that they have no opportunities to regain the money they spent on their campaigns. For a small number, suicide is the only way out.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that suicides occur predominantly among women candidates

But for this dismal background, it would be tempting to say that it is heartening news that more political candidates in Indonesia die at their own hands than at the hands of their political opponents. These suicides - and the gender politics that give rise to them - are tragic. But it is also worth celebrating the relative rarity of electoral killings in Indonesia, and reflecting on its causes.

Political killings are usually a symptom of difficulties of maintaining a monopoly of power. When political competition is fierce and the stakes are high, killing can be one way of eliminating rivals. In Indonesia, local elites have worked out ways to handle political challenges without bloodshed. Instead of squabbling fatally over the cake of political power, local elites have worked out ways to share it out. It is this dynamic that above all accounts for the fact that if parliamentary candidates in Indonesia meet their maker prematurely, they do so because of suicide not murder. ii

Michael Buehler (mb3120@columbia.edu) is a Postdoctoral Fellow in Modern Southeast Asian Studies at Columbia University and Assistant Professor of Political Science at Northern Illinois University.