Conspiracy as foreign policy

Mattias Fibiger

In defining a peculiar but persistent strain of political thought, the eminent historian Richard Hofstadter writes that ‘the distinguishing thing about the paranoid style is not that its exponents see conspiracies or plots here and there in history, but that they regard a ‘vast’ or ‘gigantic’ conspiracy as the motive force in historical events.’ These putative conspiracies are often regarded as the brainchild of a single, sinister individual, one whose powers of manipulation transcend historical contingency and the unpredictability of history’s unfolding.

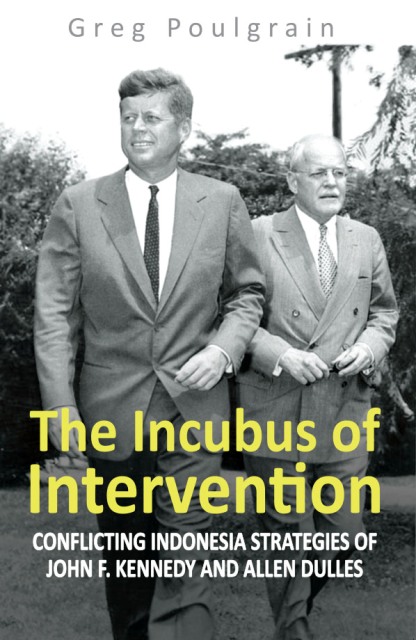

It is this spirit that animates Greg Poulgrain’s Incubus of Intervention. Poulgrain traces two stories each, he claims, intimately bound up with the other: the discovery and exploitation of lucrative natural resource reserves in Papua; and the formulation and implementation of American policy toward Indonesia.

The first story begins amidst the tumult of the interwar period. Three Dutch geologists attached to the Netherlands New Guinea Petroleum Company (NNGPM) in 1936 happened across the world’s largest gold mine, a veritable El Dorado, today owned by the Freeport corporation. Given resource-hungry Japan’s encroachment on Southeast Asia and the fragility of Dutch colonial authority in Papua, the company (together with members of the Dutch political elite) chose to conceal its discovery. That effort persisted into the postwar period, as the presence of gold in Papua was hidden from the leaders of newly independent Indonesia. Indeed, Poulgrain alleges that the gold explains the Dutch leadership’s determination to retain Dutch New Guinea in the face of nationalist Indonesians’ demands for the territory’s incorporation into the sovereign archipelago.

The second story concerns the American government’s role in the dispute over the future of Papua. Here the United States was presented with a dilemma between supporting a North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) ally and currying favor with a leader in the non-aligned movement – both vital constituencies of American power in the 1950s and 1960s. According to Poulgrain, the Eisenhower and Kennedy administrations mediated the conflict between the Netherlands and Indonesia in such a way as to secure the right to exploit Papua’s abundant natural resources for American companies. To argue for the economic underpinnings of U.S. foreign policy is of course nothing new. Revisionists like William Appleman Williams have characterised American policymakers as possessed of a broad worldview linking domestic economic prosperity to overseas economic expansion for half a century. But Poulgrain’s view is decidedly cruder. He depicts an American policymaking apparatus held hostage to the avaricious demands of a single individual whom he dubs an ‘evil genius’: Director of Central Intelligence Allen Dulles.

And it is Dulles who weaves the two stories together. Poulgrain turns first to Dulles’s early career as an intelligence officer and Rockefeller-connected lawyer in the 1920s and 1930s, claiming ‘his roles remained interchangeable between the State Department and [the law firm] Sullivan & Cromwell which was virtually the front desk of Standard Oil’. During this period Dulles helped secure a sixty per cent stake in NNGPM for Standard Oil, thus overcoming the Netherlands’ closed-off economic governance of the Indies and opening Papua to extractive American enterprises. Dulles also entered the world of covert operations, developing a skillset and network of contacts that would enable him, Poulgrain suggests, to hatch vast and shadowy plots designed to accomplish a great many nefarious objectives.

The bulk of Poulgrain’s book focuses on Dulles’s role in crafting American policy toward Indonesia during the 1950s and 1960s. He claims Dulles pursued a coherent, long-term ‘Indonesia strategy’ that began around 1957. Dulles allegedly orchestrated the PRRI (Revolutionary Government of the Republic of Indonesia) revolt in 1958 to effect the creation of a centralised Indonesian army, which could then serve as a vehicle of anti-Dutch revolution in Papua and regime change in Indonesia more broadly. To set the stage for military-led regime change, Poulgrain argues, Dulles ignited konfrontasi as a means to weaken Indonesia’s economy and exacerbate the Sino-Soviet split.

One of the book’s principal historiographical innovations is the reframing of the United States’ role in the PRRI revolt from an undifferentiated failure – a thesis put forth most memorably by George and Audrey Kahin in Subversion as Foreign Policy – to a stunning success. The revolt did indeed lead to the centralization of Indonesia’s army. Alas, though, Poulgrain’s evidentiary scaffolding cannot bear the weight of this provocative argument. He relies on little direct evidence to show Dulles intended the PRRI to have these effects. The evidence presented includes a single sentence extracted from a memorandum penned by Dulles to President Kennedy (that the revolt was ‘permitted to wither by lack of sustenance’) and interviews with General Nasution and Colonel Zulkifli Lubis (the latter of who claimed ‘the Americans tricked us’). Most of Poulgrain’s evidence is circumstantial, including the suggestion that Dulles dispatched CIA operative Frank Wisner to aid the PRRI knowing that Wisner would fail. And further, that Dulles had Allen Pope deliberately bail out of his plane while carrying documents implicating Taiwan in the PRRI in order to provide a bizarre pretext for military action against pro-PKI (Indonesian Communist Party) Indonesian Chinese.

Upon that unstable edifice Poulgrain builds his argument higher. Dulles allegedly sensed a threat to his strategy for Indonesia emanating from United Nations Secretary General Dag Hammarskjöld, who was concocting a plan that would provide eventual self-governance to Papua. Poulgrain states in no uncertain terms that Dulles had Hammarskjöld assassinated in order to forestall the implementation of this plan. The next threat to Dulles’s strategy came from President Kennedy himself, who planned to visit Jakarta in 1964 in the hope of winding down konfrontasi and improving U.S.–Indonesian relations. Poulgrain is here more circumspect, but he implies his agreement with Sukarno’s assertion that ‘Kennedy was killed precisely to prevent him from visiting Indonesia’. The culprit, the reader is left to infer, was Dulles.

These conspiratorial notes, unsubstantiated by adequate evidence, blend with the book’s sometimes confusing, non-chronological narrative style to overshadow its many achievements. Poulgrain has offered a fine-grained analysis of the role played by a single reserve of precious metals in imperial competition over the Dutch East Indies and Indonesia. As a critique of American foreign policy, however, his book misses the mark. Long after Dulles passed from the scene the United States continued to act in ways that sacrificed the rights of Papuans for the profits of Freeport-McMoRan. These policies are not personal. They are systemic.

Greg Poulgrain, The incubus of intervention: conflicting Indonesia strategies of John F. Kennedy and Allen Dulles, Petaling Jaya, Malaysia: Strategic Information and Research Development Centre, 2015.

Mattias Fibiger (mef249@cornell.edu) is a Ph.D. Candidate in the Department of History at Cornell University. He studies U.S. foreign relations and modern Southeast Asia.

Inside Indonesia 123: Jan-Mar 2016{jcomments on}