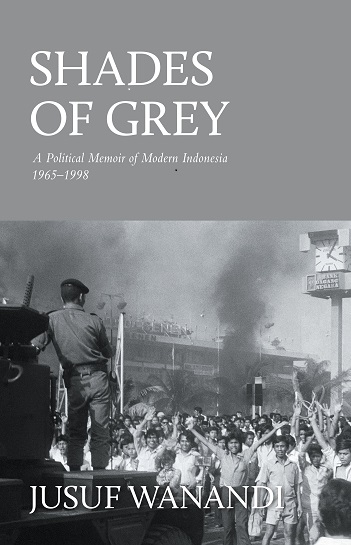

Jusuf Wanandi’s memoir allows glimpses into the mindset of Suharto-era officialdom

John Roosa

At times one comes close to feeling sorry for Pak Wanandi. So little in his life worked out as planned. The book, unlike so many je ne regrette rien autobiographies of Suharto-era officials, is filled with misgivings. He helped bring Suharto to power in 1965-66 and then regretted that the general stayed in power for so long. He rebuilt Golkar in 1970-71 and was later disappointed to see the organisation become the tool of Suharto’s personal power. He led the international PR campaign justifying the 1975 invasion of East Timor but then lamented the army’s brutal counterinsurgency tactics.

As a Chinese Indonesian, Wanandi particularly regrets the Suharto dictatorship’s blocking of his community’s access to government jobs. He changed his name from Lim Bian Kie in the spirit of assimilation only to be treated as part of a quasi-alien nation. Wanandi’s initial enthusiasm for the Suharto regime – with its promises of economic growth, political stability, and cultural tolerance – waned in the 1980s as its personalised, nepotistic, and racist character became entrenched.

Despite the author’s readiness to profess regrets, it is difficult to summon up any sympathy for him. He laboured for years on the dark side, helping the Suharto dictatorship commit a variety of crimes, and he remains proud of his work as the protégé of one of its most loathsome dirty-tricks intelligence officers, Ali Moertopo. His insider accounts of the decision-making behind various massacres are often self-serving and inaccurate.

The mass killing with which the regime began in 1965-66 was a ‘horrible mistake’. Unlike many of his New Order peers, who have either remained silent about the killing or offered full-throated justifications of it, Wanandi is at least willing to see something wrong: ‘We can never legitimise, gloss over, or forget those acts’. He even calls for investigations that can ‘bring up’ – a nicely chosen verb invoking excavations of mass graves – ‘the truths about those tragic events’.

Still, how can he call the slaughter of unarmed, defenceless detainees ‘a mistake’ rather than a crime? He can by doing what he asks us not to do. He glosses over them. He explains them with a fanciful story that blames, of all people, Sukarno. Bung Karno is supposedly at fault for not immediately banning the PKI in early October. People ‘took matters into their own hands’; in some regions, the army ‘took the initiative’. This blame-the-president story has been told before. Notosusanto and Saleh presented it in their famous 1967 tract on the September 30th Movement: ‘the public’, demanding the PKI be punished, ran amok when Sukarno tried ‘to protect the party’. The story is nonsense. Suharto and his clique of army officers sidelined Sukarno and proceeded to do what they had already planned to do. They would have used a presidential ban to legitimate their murderous assaults, just as they used his Supersemar to legitimate their March 1966 coup.

Wanandi nearly concedes as much. He claims, with remarkable frankness, that the ‘killing campaign’ in Central Java ‘was led by Sarwo Edhie’, the RPKAD commander sent there to attack the PKI in mid-October. Wanandi unfairly casts him as the sole agent of extermination. He omits Suharto’s role. And he seems oblivious to the perversity of his depiction of Sarwo Edhie’s motivations: ‘He had a personal grudge against communists to avenge the death of Achmad Yani, his friend and patron.’ Tens of thousands of ordinary civilians in Central Java, people who had nothing to do with Yani’s murder at Lubang Buaya, had to be slaughtered because Sarwo Edhie wanted to avenge the death of his old buddy from Purworedjo? Was the current president’s father-in-law that pathological? Wanandi does not mention that the student movement in Jakarta, of which he was a prominent leader, feted Sarwo Edhie as a great war hero when he returned after the killing spree.

Wanandi’s account shows how closely the student movement worked with the army. The students knew in early October that they were in no danger. The PKI put up no resistance as they rampaged through the streets, ransacking and burning houses, offices, and schools. But still they pretended as if they were brave heroes at war risking their lives. Wanandi notes in passing, without an expression of regret, that the students of the Indonesian Student Action Front (KAMI) forced people to join their demonstrations: ‘We would send civil defence (Hansip) personnel around to people’s houses, advising them that they would be regarded as PKI if they did not attend our meetings.’

Wanandi doesn’t explain precisely how and why Ali Moertopo, whom he calls Pak Ali, recruited him. He mentions that he first met him at a Kostrad ‘seminar’ in 1963 at which army officers declared that China and the PKI were their main threats, not the Western imperialist powers that Sukarno identified. (With such views being expressed, it must have been a secret, invitees-only gathering.) It was a fateful meeting: ‘I was not to know then what a great influence he was to have over my life.’

His account of Moertopo’s Opsus, the secret organisation inside Kostrad, to sabotage Konfrontasi, is as revealing as it is confusing. He claims Opsus began in mid-1965 during a meeting between Moertopo and Suharto (of Kostrad) and Yani, the army commander. But then he claims that Moertopo began contacting Des Alwi and other Socialist Party of Indonesia (PSI) figures, living abroad after their support for the failed 1957-58 rebellion, in September or October 1964. Perhaps the meeting with Yani was in mid-1964. He casually mentions, as if it was a routine matter, that Moertopo smuggled ‘rubber and other goods’ to generate money for Opsus and accumulated $17 million in banks in Singapore and Malaysia. Was the PKI’s term ‘capitalist bureaucrat’ (kabir) entirely inaccurate?

Moertopo appears in this book as a clever servant of Suharto’s. In the film about an English manor, Gosford Park (2001), a servant explains that she has to anticipate, to know what the masters want ‘before they know it themselves’. Wanandi saw Moertopo’s ‘strength’ in his ability to anticipate: ‘He always felt he had to prepare the old man [Suharto] in advance, before events happened.’

Wanandi joined Moertopo’s staff in 1967 just as the colonel became Suharto’s point man for Papua. For two years, starting in mid-1967, Wanandi was involved in the preparations for the holding of the Act of Free Choice in Papua. The strategy, according to him, was seduction. He brought in boatloads of tobacco and beer so that the Papuans would look kindly upon Indonesia. Wanandi does not discuss the coercive and deceitful tactics to win the vote, avoiding an engagement with the kind of documentation found in John Saltford’s 2003 book The United Nations and the Indonesian Takeover of West Papua, 1962-1969: The Anatomy of Betrayal, and remains silent on the terrors that Indonesia has inflicted on the Papuans since 1969. (Much of the section on Papua has already appeared in an essay Wanandi published in Inside Indonesia in 2009.

The ‘success’ in Papua emboldened Suharto’s men to attempt a similar strategy in East Timor. One of the longest sections of the book concerns Wanandi’s role in annexing East Timor in 1974-75. He is desperate to clear his name, especially now that the country has won independence, two truth commissions have issued reports exposing the Indonesian military’s atrocities and some Australian embassy files referring to his role have been declassified.

He insists that his strategy was again, merely seduction. Moertopo’s group started Operation Komodo in April 1974 for ’gathering intelligence and peddling pro-Indonesia propaganda‘ and training East Timorese to fight Fretilin on their own. They hoped to annex East Timor ‘through diplomatic means’ and then hold some kind of act of self-determination, after about seven years, once Indonesia had prepped the East Timorese so that they would vote the right way, as in Papua. The East Timorese would come to see that ‘the only logical path was to become part of Indonesia’.

As his story goes, their strategy lost out as General Benny Moerdani, the military intelligence chief, started Operation Flamboyan in early 1975, which sent Indonesian-trained East Timorese across the border to take the country by force. Then that operation lost ground to Operation Seroja in August 1975, when the military commander, Panggabean, proposed to use Indonesian troops to take East Timor. It was, Wanandi opines, a ‘stupid’ plan. Fretilin’s military victory and its declaration of independence in November provoked Suharto into opting for Panggabean’s plan. ‘The whole thing went haywire.’

While depicting Moerdani and Panggabean as the villains, Wanandi unintentionally indicts himself. At no point did his Moertopo faction envision a genuine act of self-determination for the East Timorese. The plan from the start was to annex East Timor and the debate with the other factions was only over the method.

Once the Indonesian troops launched a full-scale invasion in December, Wanandi made the diplomatic rounds: ‘It was a PR job, and not a nice one, because we didn’t agree with what was happening.’ He was in Washington DC coaching the people Indonesia sent to testify to the US Congress, explaining to them how they could not admit that the troops had ‘invaded’.

Wanandi has the remarkable ability to acknowledge a crime and then blame the victims for it. He admits Indonesian troops shot and killed five foreign journalists in Balibo to eliminate witnesses to the invasion: ‘it could not be known that they were invading’. So here is a clear admission to a war crime: the deliberate murder of non-combatants. Then he blames the journalists themselves for putting themselves in a war zone: ‘They thought it would be a picnic and of course they were shot.’ Of course.

This memoir allows us some glimpses into the depraved mindset of Suharto-era officialdom. Wanandi and his fellow Golkar leaders engineered electoral victories every five years by intimidating people. They sent civil defence personnel house-to-house to inform people that a vote against Golkar would be construed as a vote for the PKI. They organised a civil servants association as a ‘tool of Golkar to win elections’. They mobilised street toughs, the preman. Wanandi is proud of the electoral victories and is not troubled by the underhanded methods to achieve them. Pak Ali assigned him tasks and he completed them successfully. Asal bapak senang (as long as the boss is happy). Moertopo famously called commoners ‘a floating mass’; they had to be manipulated and directed because they were too stupid to think for themselves. Wanandi takes that premise for granted.

Moertopo arranged the funding for Wanandi’s think-tank, CSIS, in 1971 by calling up various Chinese Indonesian businessmen, cukong (a term Wanandi euphemistically translates as ‘patron’), and asking for money: ‘that was all that was needed’. With CSIS, Wanandi styled himself as an intellectual and cultivated contacts with foreign academics, all the while serving as a Golkar boss and intelligence operative. CSIS was another seduction strategy, this time targeting foreigners who were influential in shaping international opinion about the Suharto regime. It was also a way to monitor and punish the recalcitrant ones, like Benedict Anderson. (Anderson has written about his run-ins with Wanandi in his 1996 article in the journal Indonesia, ‘Scholarship on Indonesia and Raison d’État’.)

Wanandi would like readers to think he has a heart; that his work on the dark side has only left him streaked with grey and not dyed jet black. He recounts his lobbying in the 1970s to get political prisoners released and allow the Red Cross into East Timor. This work seems to have been greatly motivated by the need to placate foreign criticisms of the regime.

I was surprised to find Wanandi flattering my book about the September 30th Movement ‘as the best explanation of who was behind the coup and why it failed’. The praise is accompanied by a silence on my condemnation of the army’s reaction to the movement. As is his habit, he blames the victims. The movement was ‘a terrible blunder that opened the floodgates to retribution’. The PKI was responsible for the violence against it. He invokes the old cliché: the atmosphere of the time was ‘kill or be killed’. That specious depiction of the time conveniently exonerates the perpetrators who cowardly executed people who were already tied up and then made them disappear. As the recent film The Act of Killing (2012) reveals, the best way to dispel the perpetrators’ myths is to let them describe precisely what they did.

Wanandi ends his book in Candide-like fashion, bereft of the optimism that animated his early enthusiasm for the Suharto regime, writing about his think-tank as the little garden he cultivates. By the end of the book I felt like going outside and cultivating a real garden as a relief from reliving the grey-on-grey nightmare of Suharto-era officialdom.

John Roosa (jroosa@mail.ubc.ca) is Associate Professor of History at the University of British Columbia and author of Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto's Coup d'État in Indonesia (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2006).