Julian Millie and Agus Ahmad Safei

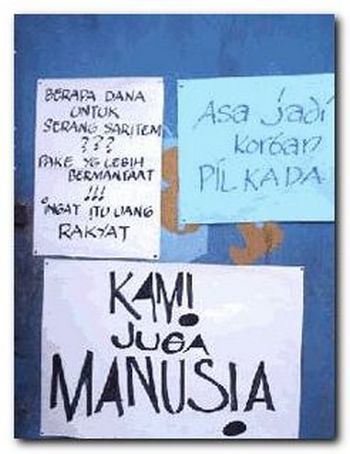

The closure of Saritem drew protests from people whose livelihoodsdepended on itUsed with permission of detikBandung |

In recent years, Indonesian governments at the district/city level have been passing laws that enforce religious prescriptions, such as Islamic deportment in public behaviour. This has been possible because the autonomy law of 2004 gave these governments the opportunity to enact laws reflecting regional culture and heritage. Some of them have quite naturally identified Islam as the primary reference for this purpose.

In West Java, a number of districts have produced such regulations, leaving some observers concerned for their effects on the rights of women, artistic practice and religious minorities. Against this background, the city of Bandung, the administrative and economic capital of West Java, has proved to be an exceptional case. Rather than producing a legislative framework that formalises Islamic norms as standards for public behaviour, Bandung’s municipal government has instead acknowledged the city’s religious diversity, developing a program called ‘Bandung: A Religious City’ (Bandung Kota Agamis). The program aims to make Bandung an environment that reflects the aspirations of all the religions followed by its residents.

Religion and civic order

Mayor Dada Rosada first presented the concept of ‘Religious Bandung’ in 2004. This move had political appeal for Mayor Dada, who was keen to respond to the perception that he was too ‘secular’, having come to the job after a long career in the public service. He does not have a santri background, and has been a long-time member of Golkar, a party with a nationalist orientation. Establishing a religious program allowed him to appease concerns from some Islamic leaders about a marginalisation of Islam in the city’s public life.

Establishing a religious program allowed the mayor to appease concerns from some Islamic leaders about a marginalisation of Islam in the city’s public life

The program was preceded by lengthy public consultations. Five Islamic organisations were prominent in this process: Muhammadiyah, Nahdlatul Ulama, Islamic Unity (Persatuan Islam), The Pesantren Communication Forum (FKPP) and the Council of Indonesian Ulama (MUI). Non-Islamic groups were also involved. Representatives of the Catholic, Buddhist, and Hindu faiths met at the NU headquarters in Sancang to produce the ‘Sancang Declaration’, which called for mutual tolerance and respect and expressed a commitment to strive together to solve social and environmental problems. The program, scheduled for 2008-2013, was then given legislative force in the Mid-Term Regional Development Plan (RPJMD), something that all district and city governments are required to produce and implement after seeking approval from the regional legislative assembly.

Rather than making prescriptions about individual behaviour – like the laws passed in other West Javanese kabupaten such as Cianjur and Garut – the program justifies civic improvement as expressions of the religious aspirations of Bandung residents. An example is the civic improvement program called Cleanliness, Order and Beauty (K-3, Kebersihan, Ketertiban dan Keindahan), which attempts to provide a humane solution to the problem of unrestrained street-side trading. This program meets demands from Bandung residents for the mayor to address what they perceive as the city’s decline into disorder, and does so with a religious justification.

Why not syariah?

While Muslims constitute around 96 per cent of the population of the city of Bandung, the Bandung civic improvement program is justified on a religious base that is broader than Islam alone. It was hoped that the term Bandung Agamis, rather than Bandung Islami, would prevent destructive debates about the program’s inclusiveness. The term ‘agamis’ is neutral in the denominational sense, so it would be unlikely that any religious community would reject it. It also recognises the plural character Bandung has acquired through its history.

West Java has a high proportion of Muslims in comparison with other provinces of Java, with the exception of Banten. But its location, natural beauty and climate made the city the preferred site of residence for Europeans, especially in the early twentieth century. The colonial activity in Bandung attracted other ethnic groups, and as a result the city’s Chinese community developed an important role as traders.

The term ‘agamis’ is neutral in the denominational sense, so it would be unlikely that any religious community would reject it

The most distinctive feature of contemporary Bandung is its status as a commercial centre. Its factory outlets for fashion attract shoppers from Malaysia and Brunei, not to mention Jakarta. This concentration of commercial interests, many of them owned by non-Muslims – along with the relatively high value of these interests – is a characteristic not shared by those cities which have implemented explicitly Islamic regional regulations.

Cities with less diverse social make-ups have tended to produce religious programs that impose specifically Islamic norms on public behaviour. The religious regulations of Cianjur, for example, require employees of the city government to wear Islamic clothing on Fridays. Meanwhile, other district governments have sponsored the installation of Islamic signs and messages in public locations. Steps such as these were contemplated in Bandung during the consultation process, but were passed over: the city’s religious character had been shaped by its social inclusiveness, it was reasoned, so its municipal religious program should preserve that inclusiveness.

A price for inclusiveness

The program has attracted very little criticism. Islamists appear to support the program, agreeing on the need to give recognition to the important role of religious minorities in the city. The owners of the city’s businesses, many of whom are Chinese, serve to benefit from its broad embrace. Many ordinary citizens are happy at the government’s commitment to civic improvements.

But the program brings with it a certain tension concerning the future of Bandung’s ‘night-entertainment’ precincts and the tone of its cultural life in general. A statement made at a consultative gathering organised by the municipal government illustrates this tension. K.H. Athian Ali Da’i, a religious leader known for his uncompromising stance on public morality, said of the Bandung Agamis program: ‘As long as the [program’s aspirations] do not gel together in actual behaviour, and as long as we remain oriented to worldly things and not to the hereafter, and as long as vice is still allowed to happen in front of our eyes, then we should not have any further hope that the Bandung Agamis program will come to fruition.’

Pak Atian, as he is known in Bandung, was expressing a key investment in the program from the city’s conservative religious constituency: the mayor must act against nightclubs, karaoke bars, billiard halls, prostitution and other ‘night entertainment’ activities. In this understanding, ‘improvement’ of public morality is a marker of success. The mayor has taken this challenge seriously, aware of his vulnerability to the charge that he is too secular.

The red light district of Saritem, near the Bandung train station, has been a test case of his resolve. The prostitution and criminal involvement in this area had long drawn opposition from Bandung residents and especially from its religious figures. Closing it down would not be an easy task, however, because a significant social and economic infrastructure had developed around the area during the 150 years it had been known as an entertainment precinct. This was not the first attempt to clean up Saritem. During the time of Governor Nuriana (1993-2003), the pesantren Dar at-Taubah (The House of Repentance) was established there, under the leadership of Kyai Imam Sonhaji of Pesantren Sukamiskin. Its goal was to equip the younger people of Saritem with skills to earn livelihoods outside the field of vice but it has not substantially changed the character of the area.

On 7 April 2007, Mayor Dada and other elected office-bearers met representatives of Islamic organisations in Bandung’s grand mosque. At this meeting, Bandung was declared ‘free of vice’ (bebas maksiat), and Mayor Dada undertook to close Saritem.

On 17 April 2007 the municipal police prevented the area’s routine activities from taking place and returned sex workers to their villages. These steps earned praise for Mayor Dada from religious figures, and criticism from the interests reliant on these activities for their livelihoods. According to some people, Mayor Dada received death threats from these interests.

Concerned intellectuals also voiced a criticism that these steps were not followed by measures to assist people affected by the closure. The mayor responded to this critique by announcing Saritem would be transformed into a ‘culinary centre’ where foods and snacks traditionally associated with Bandung would be sold to the city’s many visitors.

The risk is that the achievement of ‘soft targets’ in public morality may endanger the richness of the city’s cultural life as well as its entertainment industry

Although the project to close Saritem and two other similar locations in Ciateul (now Dewi Sartika Street) drew broad community support, in other cases the government is finding it more difficult to mediate between the religious lobby and economic stakeholders. An example is the city’s 154 recognised night spots. Yielding to pressure from some of the city’s religious figures, Mayor Dada released a circular letter (surat edaran) requiring night clubs to close during the fasting month, or face loss of their operating permits. The circular drew vigorous protest from those whose livelihoods depend on income from the venues.

The risk is that the achievement of ‘soft targets’ in pubic morality may endanger the richness of the city’s cultural life as well as its entertainment industry. In 2007, for example, the mayor used the Bandung Agamis program as a justification for banning dangdut singer Dewi Persik from performing in Bandung. He held that her erotic dance movement known as ‘the saw’ was contrary to the spirit of the program. In the same year, Miss Universe was banned.

These examples highlight the possibility that conservative Muslim groups will use the program as a tool to enforce their views about public behaviour. The program explicitly recognises Bandung’s character as a cosmopolitan environment shaped by a plural history. The big question is whether this very same plurality will be threatened by its practical implementation.

Agus Ahmad Safei (agusafe@yahoo.com) is an author and lecturer in the Dakwah and Communications Faculty of the Sunan Gunung Djati State Islamic University, Bandung, and is working towards his PhD degree at Padjadjaran University.

Dr Julian Millie (Julian.Millie@arts.monash.edu.au) is a researcher in the Department of Anthropology at Monash University.