Aceh’s Commission for Truth and Reconciliation has an important, though delicate, mission ahead

Aceh’s Commission for Truth and Reconciliation has an important, though delicate, mission ahead

The bitter 29-year civil conflict between the Indonesian military (TNI) and the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) that followed GAM’s 1976 declaration of Acehnese independence is thought to have claimed the lives of between 15,000 and 30,000 people. But there has been little systematic documentation of the extent and nature of the human rights violations committed.

Following years of lobbying by Acehnese activists for a truth commission, it seems that progress may be underway. Aceh’s provincial parliament mandated the establishment of a local Commission for Truth and Reconciliation (Komisi Kebenaran dan Rekonsiliasi, or KKR) in 2013. Last year it took the important step of selecting the commissioners. The commission is expected to begin its work later this year, but whether it will be successful remains uncertain.

The long road to the KKR

More than 10 years ago it was formally agreed that there would be a truth and reconciliation commission (TRC) in Aceh as part of a national Indonesian TRC. This was a term of the Helsinki Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) that was negotiated between the Indonesian government and GAM in 2005. The 2006 law for the governing of Aceh also provided for the TRC. But the national TRC has been in legal limbo since late 2006 when the Constitutional Court (in an apparent defence of the principle of accountability) ruled that the 2004 law under which the commission was to be established was invalid. A key issue was that the law permitted the granting of amnesty, and hence legal immunity, to perpetrators of gross human rights abuses.

In the absence of a national TRC, the Acehnese provincial parliament passed its own provincial legislation in 2013, to establish a locally mandated commission, called the KKR. A selection process was then undertaken to choose seven commissioners, who were inaugurated in October last year. Unusually for a TRC, Aceh’s KKR is envisaged as a permanent body, although commissioners will be required to apply for re-election every five years.

A key aspect of the KKR’s work will involve ‘truth seeking’. The commission is mandated to conduct systematic investigations into the causes and impacts of the conflict, including the role of state and non-state actors. After gathering information from government organisations and NGOs, and taking statements from victims and their families, the KKR will present a final report of its findings to the provincial parliament and the national government.

|

|

A community comes together to pray at the remembrance of the Simpang KKA incident. (Lia Kent) |

The KKR also has a mandate to design a reconciliation mechanism incorporating dispute resolution practices based on Acehnese adat (custom). These mechanisms are expected to be established at the local level, and will only be used to adjudicate cases that do not involve gross human rights violations. In addition, it is envisaged that the commission will recommend a reparations program, although the establishment of this program will be the responsibility of the national and provincial governments. The commission’s mandate also allows it to provide urgent services to the ‘most vulnerable victims’ in the short term to address their immediate physical or psychological needs.

Ideals and political realities

Acehnese human rights activists are hopeful that the KKR will provide recognition and practical assistance to conflict victims. They also hope that it will provide the first comprehensive account of the human rights violations that took place during the conflict, with the expectation that this might serve as the basis for prosecutions by a human rights court in the long term.

But it would be wise to temper expectations of the KKR. A key issue is the commission’s basis in provincial legislation, which means there is no guarantee of Indonesian government cooperation. Some commentators have questioned whether ‘reconciliation’ can occur in the absence of a TNI or Indonesian government acknowledgement and apology. And if the funding for reparations does not come from the Indonesian state, but from other sources, can this really be understood as reparations?

The absence of central government involvement or TNI cooperation raises other uncertainties about the nature of the ‘truth’ that will emerge from the process. Without the capacity to gather detailed information about the TNI chain of command, will enough information come to light to establish the circumstances and the perpetrators of human rights abuses? And will the facts be sufficient to serve as a basis for prosecutions? Even if they are, given that many members of the TNI implicated in the conflict remain in positions of power, it is unlikely, at least in the short term, that human rights violations reported by the KKR will be prosecuted. For conflict victims, perhaps the more important question is whether enough information will be revealed to locate the graves of the dead.

The situation is further complicated by the fact that not all of Aceh’s political leaders support the KKR. Some express concerns that the KKR will be one-sided, and will disproportionately focus on the human rights abuses committed by members of GAM over those committed by the TNI. The limited funding made available for the first year of the KKR’s operation may be evidence of this lukewarm support – the commissioners requested Rp.21 billion (A$1.9 million) for its 2017 budget, but the Aceh Parliament only approved Rp.5 billion.

Community expectations

KKR commissioners will also need to think about how to respond sensitively to those in the local population who have high expectations of practical assistance, and how to garner support from members of society who are concerned about opening old wounds.

In a context where livelihoods have been severely disrupted due to the loss of breadwinners, displacement, and the interruption of farming activities, many Acehnese look to the government for assistance to help them rebuild. The uneven forms of assistance provided to civilians affected by the conflict in the wake of the Helsinki MoU have only elevated these expectations. Many of those who identify as conflict victims express a view that they were unfairly overlooked by post-conflict assistance programs (which lacked accountability and transparency in terms of beneficiary selection). This perception of unfairness is compounded by the lack of accurate data about who has received assistance and how much. The KKR will need to take care not to raise expectations of assistance, particularly as it will not have a mandate to deliver a comprehensive reparations program.

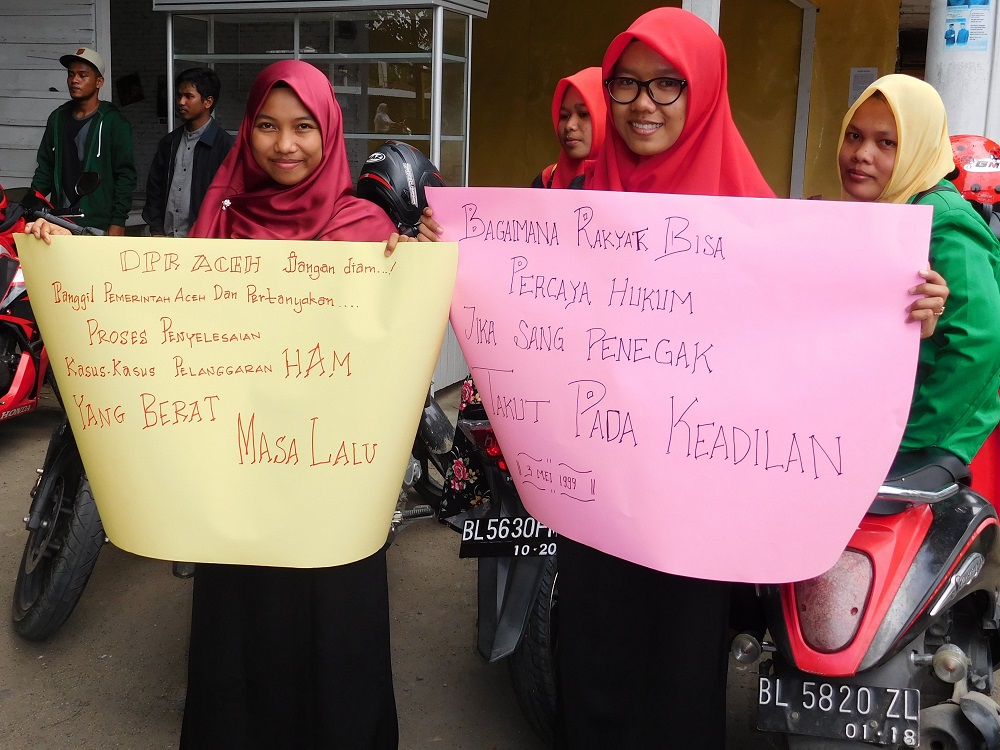

|

|

"If not now, when?" Students demand justice at the remembrance of the 18th anniversary of the Simpang KKA incident. (Lia Kent) |

A further challenge arises from the fact that it has already been ten years since the signing of the Helsinki MoU. Many ordinary people claim to have moved on with their lives. These Acehnese are concerned about ‘opening old wounds’, with some expressing the view that they have already ‘forgotten’ the violence of the past. These concerns are particularly keen in some parts of the province, such as the district of Bener Meriah, where the conflict was deeply entangled in the complex relations between local communities, rather than being a simple struggle between TNI and GAM. During our recent fieldwork, locals in this district expressed uneasiness about the idea of public truth-telling, which, some suggested, might unravel the tentative peace that exists.

Islamic leaders are also a powerful political force in Aceh, but there has only been limited consultation with them about the KKR. In order to resonate with the spiritual beliefs of much of the population, and to avoid backlash from powerful religious leaders, it will be crucial for commissioners to find ways to frame the goals of the KKR in alignment with Islamic teachings rather than secular, liberal, human rights discourses. One option might be to engage with trusted local religious leaders – some of whom are women – and village-level study groups, to explore alternative testimonial methods and forums that might provide more culturally appropriate and gender sensitive avenues for dealing with cases of sexual violence.

Gambling with truth

There is much at stake – for conflict victims, human rights activists and political leaders – in the KKR’s attempt to investigate the past. Given the political constraints, perhaps the best that can be hoped for is that the KKR will help to establish a more accurate picture of the conflict. The KKR’s documentation efforts might also provide a basis for the development of educational materials, help catalyse local forms of memorial culture and provide a useful set of recommendations around which advocacy efforts can coalesce.

Perhaps the biggest danger is that the KKR will be unable to meet high community expectations. It is possible that conflict victims may experience truth telling as another form of injustice if they are expected to tell their stories in exchange for limited personal benefit. Part of the challenge for commissioners in this context will be to listen carefully to community fears about ‘opening old wounds’ rather than downplaying them or assuming that, for victims, speaking out is always a therapeutic experience. And, to touch the lives of the population, commissioners will also need to find ways to ground the KKR in frameworks that resonate with local cultural and religious values.

But for all its potential shortcomings, the KKR represents an important development in the Acehnese human rights landscape. While it may not produce a truth that is as complete as activists would like, it might at least help to challenge official attempts to downplay the extent of the violence that took place.

Dr Lia Kent (lia.kent@anu.edu.au) is a fellow in the School of Regulation and Global Governance at the Australian National University.

Rizki Amalia Affiat (riz.affiat@gmail.com) is a Jakarta-based researcher for ICAIOS (International Center for Aceh and Indian Ocean Studies) and editor of Islambergerak.com.

A longer version of this article will appear as a book chapter in:

|

David Webster (Ed), Flowers in the Wall: Memory, Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste, Indonesia and Melanesia, University of Calgary Press (forthcoming 2017). |

Related articles from the archive

|

May 18, 2017 |

|

|

Oct 05, 2014 |

|

|

Jun 07, 2009 |