Bob Lowry reviews the memoir of the current Jakarta governor and likely frontrunner for the 2014 presidential elections

Bob Lowry

Joko Widodo, popularly known as Jokowi, is a classic rags-to-riches tale. Born in Solo (Surakarta), Central Java, in 1961, he was the oldest child of a family of four and the only son. His father was a struggling small-time timber collector. The family lived in flimsy run-down rented shacks on the flood-prone banks of a river. Nevertheless, his family assisted him through school and he eventually graduated with a degree in forestry from Gadjah Mada University in Jogjakarta, in 1986.

Jokowi joined the forestry service of a state enterprise in Aceh before returning to Solo in 1989 to work with his uncle and learn the furniture business from design to delivery. Then he branched out on his own. He was the beneficiary of a small loan from his father and later a government business sponsorship scheme, and soon established a thriving furniture business with a strong export focus. In a searing experience in 1990, one customer in Jakarta refused to pay for a large order, almost bankrupting him. By severely cutting back his business and with determination, however, he endured and soon rebounded.

He established a strong overseas market for his products. At one point he had over 1000 people working for him in multiple locations. His entrepreneurial flair was recognised by business associates who nominated him to head a newly established branch of the furniture manufacturers association in 2002. His success in this role prompted his colleagues to press him to run for mayor of Solo, one of the historic cities of Central Java. He won the 2005 mayoral election under the banner of Megawati Sukarnoputri’s Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (PDIP). He won a second term in 2010.

His strategy was to revive Solo through preserving and promoting its historic attributes without discouraging modernisation. Rather than sending out municipal police to clear street traders blocking traffic, he engaged them in lengthy discussions and created safe and accessible places where they could improve their trade. Walkways and historic modes of transport were revitalised or built to encourage people back onto the streets of the city. Zoning laws were enforced to prevent the ‘mallisation’ of the historic core of the town. His success was such that mid-term he was nominated by PDIP to run for governor of Jakarta. He succeeded in ousting the favoured incumbent in the 2012 elections. In a sign of his political acumen, he went to great lengths to explain his reasons for leaving to the people of Solo and convey his confidence that they would preserve and continue the city’s progress.

Leading through example

The memoir shows Jokowi to be a politically astute, compassionate conservative who believes that the role of government is to unleash the genius of the people, not mollycoddle them. He has a hands-on style of leadership and seeks to give hope to the poor by engaging them directly and giving them access to education, health care and basic services. As a businessman and reform-oriented politician he has a visceral hatred of corruption and the labyrinthine bureaucracy in which it thrives. He gives his bureaucrats little quarter. He does not claim to have the answers to all of Indonesia’s problems, but he passionately believes that humans can produce the answers to human-made problems. He is ready to draw on the expertise and experience of those who can help solve the problems he confronts. He has recently held extensive discussions with the Singaporeans, for example, on how to manage the construction of a MRT in Jakarta. Work on the project has already begun.

Jokowi currently claims to have no ambitions beyond fixing the long neglected infrastructure problems of Jakarta and improving the lot of its poor. However, any reading of the book leaves no doubt that he is willing to be a contender if called. Marcus Meitzner, a leading Indonesian scholar at ANU, has already called the election in his favour. The polls also seem to indicate that he would win a presidential election. In some recent polls, Jokowi has doubled the percentages of his nearest rivals.

Preparations are underway for the presidential elections this year. Jokowi can likely afford to stand back until the parliamentary elections in April-May, which will determine the parties entitled to run a candidate in the presidential election. However, he may be called earlier, as any party hoping to nominate him will want to draw on his popularity in the parliamentary elections. The obvious party to nominate him is PDIP. However, party chairwoman Megawati, responsible for nominating PDIP’s presidential candidate, is thought to still harbour hopes of running herself, even though polls indicate that this would be disastrous for her party.

Brand ‘Jokowi’

Jokowi is not a great or inspiring public speaker, but he is a master of symbolism and ‘branding’. Nothing is left to chance, be it dress, mode of transport or unannounced inspections and visits. He understands that he is an outsider, and that he must strengthen his robust social base outside but not independently of the prominent political parties. As the leader of a new breed of Indonesian politicians, he is a media darling. His consultative, no-nonsense and hands-on leadership style has endeared him to a people crying out for an end to ineffective and corrupt government, which has been unable to address the challenges of an economically thriving but politically stunted country. The current president has brought stability, but fundamental reform has stalled under his overly cautious leadership and a fractious and compromised parliament.

So if he is called, agrees to run, and wins, what sort of president would Jokowi make? First and foremost, he brings very little political baggage. His personal wealth has insulated him from the taint of money politics and cronyism. He is not driven by ideology and is a pragmatic, astute problem solver with a deep commitment to reform. For example, he is making the Jakarta provincial budget and associated expenditure public. He demands that merit be a major consideration in the selection of public officials.

The same would probably be true for foreign and defence policy, despite his lack of experience in these fields. There is unlikely to be any fundamental changes in Indonesia’s non-aligned independent foreign policy, in which, in the words of President Yudhoyono, it seeks ‘a million friends and no enemies’. Nevertheless, he would likely be more pragmatic and focus on those relationships and activities that would contribute most to enhancing Indonesia’s domestic modernisation, reform and security.

He would, however, have to operate in a much more complex, fragmented and challenging political environment than he currently faces or has previously experienced. Despite his personal integrity, he will be pounded by the political and economic interests of the parties that support him. He will also face the strong protectionist and nationalist sentiments that confound seeking sensible solutions to seemingly simple problems, such as scrapping government fuel subsidies or redrawing the maritime boundary between East Kalimantan and Malaysia.

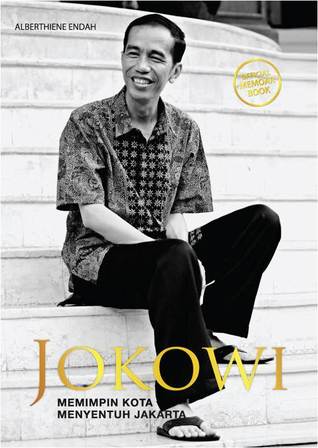

The book is carefully crafted and produced. It outlines his early life and family struggles, and his challenges, trials and tribulations as a businessman and politician. It is well written and reminds this reviewer of Obama’s Dreams of My Father. The photos of Jokowi bear at least a passing resemblance to Obama, especially where he is dressed in an open necked white long-sleeved shirt.

The book has a simple but striking cover starring a casually dressed and relaxed-looking Jokowi. It ends with a full range of photos showing him in a cross-section of social settings. This is in stark contrast to the expensive and vacuous hagiographies of New Order era and more recent leaders.

Whether his fate is to become president or remain governor of Jakarta, Jokowi will be more than a footnote in Indonesian history.

Jokowi: Memimpin Kota Menyentuh Jakarta (Leading a Town Reaching Jakarta), edited by Alberthiene Endah, (PT Tiga Serangkai Pustaka Mandiri: Jakarta, 2012).

Bob Lowry (robertwlowry@bigpond.com), is author of The Armed Forces of Indonesia, (Allen & Unwin: St Leonards, 1996); Fortress Fiji: Holding the Line in the Pacific War, 1939-45 (Self: Sutton, 2006); and The Last Knight: A Biography of General Sir Phillip Bennett AC, KBE, DSO (Big Sky Publishing: Newport, 2011).