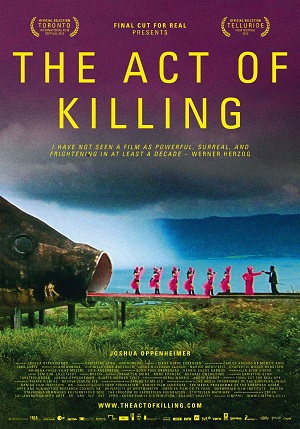

Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing is a bold, disturbing and ultimately unsatisfactory exploration of the place of violence in modern Indonesia

Robert Cribb

Credit: Final Cut for Real

Filmed over several years in the North Sumatra capital, Medan, The Act of Killing is a sprawling work that encompasses three distinct, though related, stories. The core of the film consists of the reminiscences of an elderly gangster who took part in the massacres of Communists in 1965-66. Anwar Congo appears early on in the film as a genial old man, but his subdued charm evaporates as he begins to recount, and then to re-enact, the killings that he carried out. He takes the film crew to the rooftop where he garrotted his victims with wire to avoid making a mess with blood. Using an associate as a stand-in, he demonstrates the technique of slipping a wire noose over the victim’s head and twisting it tight for as long as was needed to bring death. One of Congo’s friends describes killing his girlfriend’s father, while another recalls his rape of 14 year old girls, exulting in the cruelty of the act.

Pleasure in killing

The pleasure that Congo and his friends take in the memory of cruelty makes The Act of Killing a difficult film to watch. Not surprisingly, audiences have viewed it as a courageous revelation of the darkest secrets in Indonesia’s recent past. Yet the film’s depiction of the terrible months from October 1965 to March 1966 is deeply misleading. Although the opening text tells viewers that the killings were carried out under the auspices of the Indonesian army, the military is invisible in the film’s subsequent representation of the massacres.

The killings are presented as the work of civilian criminal psychopaths, not as a campaign of extermination, authorised and encouraged by the rising Suharto group within the Indonesian army and supported by broader social forces frightened by the possibility that the Indonesian communist party might come to power. At a time when a growing body of detailed research on the killings has made clear that the army played a pivotal role in the massacres, The Act of Killing puts back on the agenda the Orientalist notion that Indonesians slaughtered each other with casual self-indulgence because they did not value human life.

Bravado, memory and manipulation

The film makes no attempt to evaluate the truth of Congo’s confessions. Despite persistent indications that he is mentally disturbed, and that he and his friends are boasting for the sake of creating shock, the film presents their claims without critique. There is no reason to doubt that Congo and his friends took part in the violence of 1965-66, and that the experience left deep mental scars, but did they kill as many as they claim? At times they sound like a group of teenage boys trying to outbid each other in tales of bravado.

There is no voice-over in the film. The protagonists seem to speak unprompted and undirected. Towards its end, however, the film portrays an incident which, to my mind, casts doubt on its apparent claim to present an unmediated portrait of the aged killer. Returning to the rooftop scene of the murders, Congo seems to experience remorse. Twice, he vomits discreetly into a convenient trough on the edge of the rooftop, before walking slowly and sadly downstairs. By this time in the film, Oppenheimer has made clear that Congo regarded him as a friend. Did Oppenheimer really just keep the cameras running and maintain his distance while his friend was in distress? Did Congo really think nothing of vomiting in front of the camera, under studio lights, and walking away as if the camera were not there? The incident seems staged.

The sense of manipulation is all the stronger in those scenes that present the second story. Congo and his friends plan a film about their exploits in 1965-66, and The Act of Killing is interspersed with both excerpts from the finished film and scenes of prior discussion and preparation for the filming. Neither the plot nor the structure of this film-within-a-film is ever made clear. Instead we see extracts that are alternately vicious (torture scenes and the burning of a village) and bizarre. A fat gangster called Herman Koto appears repeatedly in drag, sometimes in a tight pink dress, sometimes in a costume recalling an extravagant Brazilian mardi gras. Some scenes resemble the American gangster films that Congo tells us he used to watch; some are more like the modern Indonesian horror-fantasy genre, complete with supernatural beings.

The apparently finished scenes that we see from this film-within-a-film are slick. The cinematography is expert, the costumes and sets are professional. It seems too much to imagine that a retired gangster like Congo or a cross-dressing thug like Koto could have produced something of this quality on his own. Nor did they need to, with a professional film maker like Oppenheimer in house. Yet the film is presented as the work of Congo and his friends. It is hard not to sense a betrayal here. Congo and his associates seem to have been lured into working with Oppenheimer, only to have their bizarre and tasteless fantasies exposed to the world to no real purpose other than ridicule.

The politics of gangsterism

In the third major element in the film, Oppenheimer takes us beyond the confessional and the studio into the sordid world of the Medan underworld. Actually, it is hardly an underworld. Gangsters hold high government office, members of the paramilitary Pemuda Pancasila (Pancasila Youth, PP) strut through the streets, a gangster called Safit Pardede openly extorts protection money from Chinese traders in the Medan market, and the nation’s Vice President, Jusuf Kalla, attends a PP convention to congratulate the gangsters on their entrepreneurial spirit. The title of the film-within-a-film, Born Free, deliberately echoes the identity claimed by the PP for itself as preman, or 'free men'.

Oppenheimer films the PP leader, Yapto, as an accomplished capo who can be suave or coarse as required. Another PP leader proudly shows off his collection of expensive European kitsch. ‘Very limited’, he grunts, self-satisfied, as he paws piece after piece. The condescension that Oppenheimer shows to the Indonesian criminal nouveau riche is unfortunate because it trivialises the film’s powerful portrayal of the shamelessness of the Medan gangster establishment and its close connections with political power.

Whatever might be criticised in the rest of the film, anyone interested in modern Indonesia will want to watch the scenes in which Safit Pardede prowls through the Medan market collecting cash from his small-trader victims. Manipulative and misleading The Act of Killing may be; it is nonetheless an extraordinarily powerful film which we should not ignore.

Robert Cribb (robert.cribb@anu.edu.au) is a professor of Asian history and politics at the Australian National University.