Newly discovered military documents detail culpability for the 1965 genocide. Why has it taken so long to find them?

Jess Melvin

On a hot afternoon in 2010, I returned home from the former Indonesian Intelligence Agency’s archives in Banda Aceh with a heavy cardboard box filled with photocopied documents. Having spent many hours in Indonesian government archives researching the military’s involvement in the 1965 genocide, I did not expect too much from the documents. Despite the best efforts of researchers, the only official documents yet found from the 1965–66 period were those that had been released by the Indonesian government. Among these propaganda accounts was the widely circulated pamphlet, ‘The 40 Day Failure of the “G.30.S”: 1 October - 10 November 1965’, produced by the Department of Defence and Security in December 1965. These documents denied military agency, instead attributing the violence to a ‘spontaneous uprising’ of the people’.

Such depictions clearly defied the eyewitness accounts of the genocide that had first trickled and then flooded out of Indonesia. These accounts formed the backbone of many academic studies pointing to the central role of the military behind the violence. Without documentary evidence, however, it remained difficult to pinpoint the chains of command and the orders responsible for it.

As I began pulling the documents out of the box I could hardly believe what I was seeing. They were internal files produced by the Indonesian military and government during the height of the genocide in Aceh. The documents meticulously detailed the role of the military in initiating and implementing it. They also provided evidence of the military chains of command and orders that drove the killings and helped to explain the nature of civilian participation in them. The documents demonstrate that the military leadership understood and implemented what they called the ‘annihilation of the PKI [Indonesian Communist Party]’ as an intentional and centralised national campaign.

The campaign was launched as an aggressive attack, from 1 October 1965 conceived of as a means of seizing state power by bringing the executive functions of the state under military control and physically annihilating the military’s political enemies. It involved a full mobilisation of the military, civilian government and civilian population and was coordinated nationally from Jakarta through a series of orders that stretched down from the national to the sub-district level. In Aceh, the documents show, this campaign appeared to pass through four main stages: an initiation phase lasting between 1 October and 5 October; a period of public killings beginning on 6 October; a period of systematic mass killings at military-controlled sites beginning on 14 October; and a consolidation phase that ran from December 1965 until mid-1966.

Approximately 10,000 men and women were killed in Aceh as a result of this campaign, part of an estimated one million people killed nationally. Individuals were targeted due to their affiliation, real or imagined, with the PKI.

My reason for calling these events genocide is twofold. The term was coined by Rafael Lemkin during the 1930s–1940s to describe the deliberate and systematic killing of members of a target group with the intention of destroying it. Groups identified by their political identity were subsequently excluded from the legal definition of genocide adopted by the United Nations in 1948, which only includes targeting of ‘national, ethnical, racial or religious’ groups. The reason for this exclusion was political and blurs whether it is the way in which a perpetrator group attacks a target group (i.e. for systematic destruction) or the way in which a perpetrator group identifies a target group that should take precedence when identifying cases of genocide. By Lemkin’s original concept, the 1965–66 killings were an act of genocide. Some of the killings still fit the current legal definition of genocide, since the military in Aceh (and possibly elsewhere) specifically targeted members of the ethnic Chinese community in North Aceh during the final stage. The military’s definition of its target group as ‘kafir’ (atheist) may also indicate that victims were targeted due to their (lack of) religious identity, so the acts could also be considered as being directed against a ‘religious’ group. Regardless of terminology (and leaving aside further discussion of an ‘intent to destroy, in whole or in part’), the possibility of pinpointing orders and chains of command proving military intent to systematically, physically annihilate the PKI is of the greatest importance.

Initiation phase

During the initiation phase, the documents reveal, the provincial military leadership received orders from Jakarta and Medan to launch its attack against the PKI. The first of these orders, sent via telegram during the morning of 1 October, recognised Suharto’s leadership of the Armed Forces and directed Aceh’s Military Commander, Brigadier General Ishak Djuarsa, to await further instructions. At midnight on the evening of 1 October, these instructions would be delivered at a public speech in Medan by Sumatra’s Inter-Regional Military Commander, Lieutenant General Ahmad Mokoginta, who declared: ‘It is ordered that all members of the Armed Forces resolutely and completely annihilate this counter-revolution [the 30 September Movement] to its roots’. This is the earliest known documented order issued by the military leadership to ‘annihilate’ its political enemies.

On 4 October, this order was extended to members of Aceh’s civilian leadership and provincial government. In the presence of Brig-Gen Djuarsa, they signed a declaration agreeing: ‘to determinedly annihilate that which calls itself the “30 September Movement” along with its lackeys’. Still under the watchful eye of Djuarsa, this group of civilian leaders then signed a second document declaring: ‘It is mandatory for the People to assist in every attempt to completely annihilate the Counter Revolutionary Thirtieth of September Movement along with its Lackeys.’ This document, the first of its kind to be found, is evidence that the military ordered civilians to participate in the killings. It shows that civilian participation in the genocide, no matter how enthusiastic it was at times, was ultimately coerced.

Public killings

During the period of public killings, the province entered its first wave of physical violence. Following the consolidation of the military’s intentions to attack the PKI and its order that civilians participate in implementing the violence, the military recorded the outbreak of anti-PKI demonstrations throughout the province. These demonstrations escalated and PKI offices and homes were burned. In some cases, it is recorded, victims were killed directly at the scene, while in many others victims were abducted and their bodies later discovered dumped in the street.

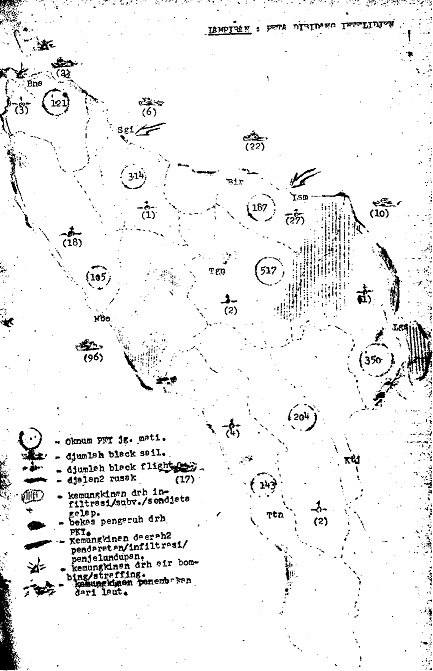

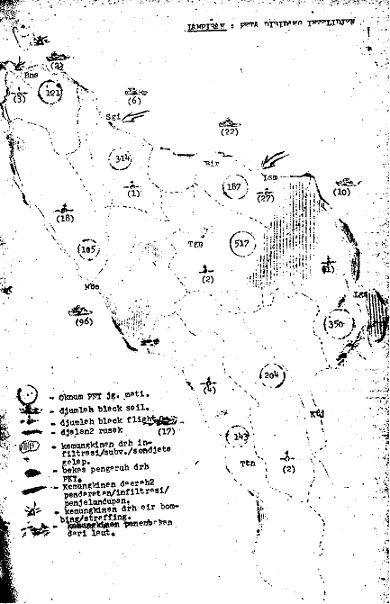

The military disingenuously claims not to have known who performed these killings. Not only had they ordered that such actions take place, they also meticulously documented their progression. A ‘death map’ and flow chart they produced graphically record the number of civilians murdered in each of Aceh’s eight districts. In total, 1941 public killings are recorded throughout Aceh. These figures do not include the killings at mass grave sites that would shortly occur throughout the province. They do, however, provide an indication of the scale of the killings. If, for example, five people were killed at mass grave sites for every person killed publicly, it is possible that approximately 10,000 people were killed in total in Aceh. This figure is, of course, speculative and will remain so until a dedicated village-by-village survey is conducted.

The military used the violence of the pogroms and public killings to instil terror in the community and to establish the PKI as a legitimate target for extrajudicial violence. The military also used the cover of public violence to demand that all individuals who had been identified as affiliated with the PKI ‘surrender’ themselves to the military.

Direct military involvement in mass killings

The decision to begin systematic mass killings appears to have been made on or around 14 October. Forced to decide what to do with their large prison population, the military chose to physically exterminate it. On 14 October, the documents show, Djuarsa established a ‘war room’ to oversee this next phase. The purpose of the war room, Djuarsa explains in one internal document, was to: ‘enable KODAM I [military area command] to carry out NON-CONVENTIONAL war in accordance with the Concept of Territorial Warfare’ [emphasis in the original]. The war room, Djuarsa continues, enabled the military ‘to succeed in annihilating them [the PKI] [by acting] together with the people…’

During this period, political prisoners were transported to designated military controlled killing sites throughout the province, where they were murdered en masse, either directly by military personnel, or by designated executioners drawn from the local community. Documentary evidence of this practice can be found in a ‘transfer list’ recovered from North Sumatra, which records the release of prisoners from military-controlled jails in Sialang Buah to members of the Komando Aksi death squad for execution. The documents from Aceh show that this systematic killing campaign, intended to physically annihilate the PKI as a group, was centrally coordinated by the military leadership and was carried out in each of Aceh’s districts.

Consolidation phase

During the final, consolidation, phase, the military acted to bring an end to the physical violence. In doing so, the leadership angered members of the newly formed KAMI/ KAPPI student militia groups, who wished to continue to escalate violence against Aceh’s ethnic Chinese community. Until this point local student militias, led by youth from the Islamic Students Association (HMI) and the Islamic Students of Indonesia (PII), had participated in the killings either directly under the leadership of the military or through their involvement with the military-sponsored Pancasila Defence Front death squads. But documents show that the military leadership became frustrated with its former student protégés during this period, since they continued to destabilise the province. This frustration was not based on concern for the victims but rather on strategic calculations. Indeed, documents show the military initially attempted to placate KAMI/ KAPPI by permitting a third phase of killings that targeted Aceh’s ethnic Chinese community.

The military also conducted large-scale purges of Aceh’s civil service at this time, exposing their long-term ambitions to not only capture the Indonesian state but also recreate it in its image. It is perhaps this consolidation phase that best demonstrates the carefully calibrated and intentional nature of the military’s attack against the PKI. The purpose of the genocide was not to create violence for the sake of violence, but to bring the military to undisputed power. It was this calculation that guided their actions at each stage of the campaign.

A legacy of impunity

As I coaxed this information from the military documents, my mind could not help but draw comparisons between the military’s campaign in Aceh in 1965 and the campaign that it would later wage to crush the Acehnese independence movement between 1978 and 2005. That military campaign had also been fought as a territorial warfare campaign involving the mobilisation of the civilian population and the use of military-sponsored civilian militia groups and death squads. These anti-separatist militias, such as the Front Pembela Aceh (Aceh Defence Front), which operated in East Aceh during the early 2000s, had followed in the footsteps of anti-communist militias before them, receiving directions, guns and money from local inter-district military commanders. In many ways, the two campaigns act as bloody bookends to the New Order regime.

Military terror in Aceh

I witnessed the end of the military’s war in 2005, when I first travelled to the province in the weeks following the Indian Ocean Tsunami. The fear created by military terror was palpable. I passed through numerous military roadblocks, watched evil-looking armoured tanks patrol the streets, and heard gunfire at night. I heard endless stories of lost friends and of family members killed due to their alleged association with the separatists or for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and of survivors stigmatised for their relationships with victims. I heard of mass graves and of mutilated bodies left by the side of the road as a warning. I met young men and women who had been hunted, tortured and beaten for their involvement in the pro-referendum movement. I saw a fear in people’s eyes that I had never seen before. People spoke in hushed voices, in code, switching conversation when someone they did not know walked by, never knowing who was friend or foe. When I later saw the same look of fear in the eyes of survivors of the genocide, I realised that fear traumatises communities long after physical violence ends. This fear and trauma has stopped so many survivors of the genocide from speaking out and has made investigating it a fraught process.

The importance of ’65 today

Reformasi saw the abolition of reserved military-only seats in parliament and a dramatic reduction in the use of military terror as a form of social control. Yet the long shadow of Suharto’s New Order dictatorship continues to haunt Indonesia. The shadow can be seen in the Indonesian Attorney General’s steadfast refusal to initiate a formal investigation into the 1965–66 killings, despite the courageous efforts of the national human rights commission to expose military culpability for the violence. Just this August, Indonesia’s house of representatives announced its opposition to President Jokowi’s plans to offer a formal apology to victims of the genocide. It warned that such an apology could spark ‘new conflict’. The threat appears to have contributed to Cabinet Secretary Pramono Anung’s announcement on 22 September that plans for an official apology have been shelved.

It is true that a serious investigation into the genocide risks upsetting the status quo in Indonesia. But this is exactly what is needed. Much of Indonesia’s old-guard political and economic elite gained their positions and wealth by supporting the military dictatorship. They find addressing ‘65 so confronting precisely because to expose the criminality of the New Order regime is to expose the system that made them who they are. Without a clean break with this past, new generations of political leaders will continue to be compromised by their association with this old guard.

The need for further action

It is time to not only support the call for an official apology, but to demand official recognition of military agency behind the genocide, accompanied by a full disclosure of all related official documents. This demand must also include a full disclosure of the role played by American, British and Australian governments in supporting and facilitating the violence. As the genocide passes its first half-century, with many of those directly responsible having already died, taking their secrets with them, there is simply no time to waste.

Jess Melvin (jmelvin@unimelb.edu.au) completed her PhD, Mechanics of Mass Murder: How the Indonesian Military Initiated and Implemented the Indonesian Genocide: The Case of Aceh, at the University of Melbourne in 2014.