Andrew Rosser

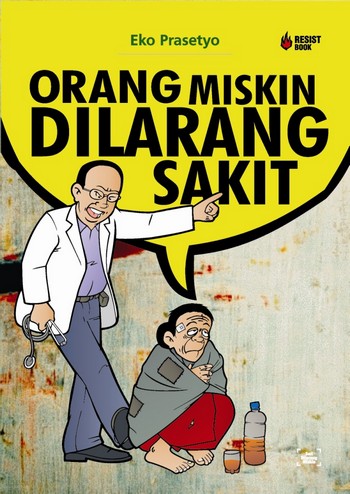

The cover of Eko Prasetyo's book, Poor People Are Forbidden to be Sick, captures well the challenge that poor people in Indonesia face in gaining access to health care |

In late November last year, according to online news service Okezone, a poor woman named Yusleni arrived at Banda Aceh Women and Children’s Hospital to give birth to her second child. She was admitted to the emergency room and given an infusion. While in the emergency room, her husband completed the necessary paperwork to register her and arrange for the birth to be covered by Jamkesmas, a national health insurance scheme for poor people that pays hospitals a much lower rate than they are able to charge other patients. About an hour later, a hospital medical officer advised them that there were no beds available and that they would have to look for another maternity hospital. With Yusleni in advanced labour, she and her sister hailed a becak and, in the middle of the night, started looking for a local midwife to deliver the baby. Barely 300 metres down the road they were forced to turn back after her sister noticed that the baby’s head was already visible. This time the hospital found her a bed in the emergency room, and took care of the remainder of the delivery. Yusleni survived the ordeal, as did her baby, although the child required continued hospital treatment because of low birth weight.

Yusleni’s story is indicative of the difficulties that many Indonesian women, particularly from poor backgrounds, face in obtaining good quality affordable maternal healthcare through the Indonesian health system. More than a decade after a severe economic crisis that precipitated widespread civil and political unrest and the collapse of the New Order regime, Indonesia is again widely seen as a development success story – indeed, it is sometimes referred to as one of Asia’s ‘rising powers’. But in the area of maternal health, the successes have been modest and much remains to be done.

Progress so far

In 2000, the international community under United Nations auspices established a set of development targets known as the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), all of which are meant to be achieved by 2015. Indonesia is on track to meet many of these goals, particularly those related to the number of people living on less than US$1 per day, the proportion of children under 5 years of age who are underweight, universal primary school enrolment and completion, gender equity in education, literacy, child mortality, and the incidence of diseases such as tuberculosis and malaria.

But it is well off track when it comes to goals related to maternal health. The country’s maternal mortality ratio – that is, the number of maternal deaths per 100,000 live births – is 228, well below the 1991 baseline figure of 390 but well above the MDG target of 102. If current trends continue, the country will miss this target by a considerable margin. Indonesia is also failing to meet its targets on the use of modern methods of contraception and reducing the ‘unmet need’ for family planning – that is, the proportion of couples who want to limit the number of children they have but do not have access to contraception.

Weaknesses in the system

There are a number of reasons why Indonesia has done so poorly in these respects. One is that many women are less fortunate than Yusleni and give birth without any assistance from a health professional, even though such assistance is a key preventative measure against maternal (as well as child) mortality. According to current official figures, almost one-quarter of births in Indonesia occur without the assistance of a doctor, nurse or midwife. At the same time, there is enormous variation by region and class. While 98 per cent of births in Jakarta involve a health professional, only 42 per cent of those in Maluku do. Seventy per cent of Indonesia’s wealthiest women give birth with the assistance of a health professional but only 10 per cent of its poorest women do.

Another problem is poor administration and underfunding of government schemes aimed at funding maternal health care to the poor. Many poor people who are eligible for Jamkesmas cards do not receive them because of corruption and mistargeting. In some cases, local officials simply sell them to the highest bidder or give them away as a bribe to voters at election time. At the same time, underfunding of the Jamkesmas scheme means that, as Yusleni discovered, health providers in Indonesia have little incentive to provide health care to Jamkesmas patients because they can make more money by serving non-poor clients who pay a higher rate out of their own pocket. Poor clients consequently find it difficult to get admitted to hospitals and often get shabby treatment when they are admitted.

Recognising the limitations of Jamkesmas, the government has responded by introducing a new maternal health insurance scheme aimed explicitly at reducing maternal mortality. Known as Jampersal, this scheme is available on a universal basis – that is, to all women regardless of income or social background – rather than being targeted at the poor. As such, poor people do not need to present a Jamkesmas card when seeking to use the scheme, which is open to any woman with an identity card (KTP). While many poor people in Indonesia do not have KTPs, they are probably easier to obtain than Jamkesmas cards and the fact that they are useful for other things provides added incentive for poor people to get them. The Jampersal scheme appears to suffer from the same problems of underfunding as Jamkesmas, although the government has announced a significant increase in spending on the program for 2012.

Political obstacles and solutions

But perhaps the most worrying issue with Jampersal is that it does not address the underlying political obstacles to improving maternal health outcomes in Indonesia. The public health system in Indonesia is dominated by officials who have an interest in starving the health system of funds in order to finance more lucrative ‘projects’ in both health and other sectors, and in using health facilities to generate rent-seeking opportunities. At the health facility level, the focus is consequently on securing kickbacks from supply, building and employment contracts and maximising revenues from clients – giving them a strong incentive to serve middle class clients who can pay the full cost out of pocket rather than poor clients who cannot.

At the same time, poor women are not well-organised in relation to health issues. What activism there is around these issues comes from a small group of NGOs that are poorly funded, limited in the geographic scope of their operations and, in some cases, motivated by perceived business opportunities rather than a concern for the poor.

This is not to dismiss the potential of schemes such as Jamkesmas and Jampersal to make a difference. Health economists emphasise the need for additional public money to be pumped into the health system when free health care schemes are introduced. Jamkesmas and Jampersal clearly contribute in this respect, even if they do not provide all the required funding. However, the fact that there are crucial political obstacles to reducing maternal mortality suggests that more is required than just additional money. Reducing maternal mortality also requires the empowerment of poor women in relation to the state officials who control the public health system. Only when poor women are able to influence policy-making decisions at both the governmental and health facility level and hold unscrupulous health professionals accountable will they be able to access the services required to ensure safe motherhood.

Empowering poor women requires measures that serve to help them organise around health issues, enhance the ability of NGOs to engage in lobbying and monitoring activities on their behalf, and the ability of these very different groups to come together. Donors interested in achieving the MDGs will need to attend to these issues, not just the technical aspects of maternal health care, if they are to have any hope of achieving the 2015 targets.

Andrew Rosser (andrew.rosser@adelaide.edu.au) is Associate Professor in Development Studies and Associate Director of the Indo-Pacific Governance Research Centre at the University of Adelaide.