Recent ground-breaking publications, an internationally award-winning film and a major conference are opening up new truths about Indonesia’s past

Gerry van Klinken

A researcher comforts her informant Memori-Memori Terlarang

The most extraordinary achievement of the New Order might have been the tenacity of its ideology. Fifteen years after Suharto was forced to resign by the democracy movement, there is still no national monument to the hundreds of thousands of citizens murdered by the military and their right-wing allies in the years 1965-68. No school textbook describes what happened. Not one museum confronts visitors with the greatest national tragedy in the history of the nation. No national day of remembrance mourns the dead and those imprisoned without trial. No state institution is attempting to record the names of the victims, the identities of family members who require compensation for their suffering, or the locations of the thousands of mass graves scattered over the archipelago. No one has been prosecuted for crimes against humanity. ‘Imagine if the Nazis had won and then they finished the Holocaust and they went back to ordinary business, doing business with the rest of the world that they were unable to conquer,’ director of internationally award-winning 1965-1966 documentary, The Act of Killing (2012) American Joshua Oppenheimer said recently. ‘That's what Indonesia is like.’

That callous tenacity, which has for half a century, dehumanised millions of citizens now seems about to crack. Many ex-political prisoners have freely published their memoirs since 1998. The National Human Rights Commission last year handed a report on the events to the public prosecutor, urging him to commence criminal proceedings against those responsible. The national weekly Tempo about the same time produced a thick special edition on the episode. Mainstream televisions stations have shown documentaries. President Yudhoyono is said to be considering a national apology.

The three publications under review suggest that a new generation wants to make a break with militarist ideology. To them, 1965 is no longer a threatening ‘now’ but an exotic moment in a past that they want to explore. The New Order narrative of the six generals whose death justifies the murder of countless civilians no longer makes sense to them. Today’s prosperity makes yesterday’s fears of political apocalypse seem unreal. Perhaps more important than anything else is a geopolitical shift. Where China was once seen as a communist devil and America as a generous aid donor, the current generation sees America as an arrogant, anti-Islamic military power and China as a model of disciplined, civilised economic growth. Golkar works with the Chinese Communist Party. Moreover, young people are beginning to realise that the social justice projects they are excited about were pioneered by the communists in the early 1960s.

New Perspectives on the 1965 Violence in Indonesia is a collection of papers presented at a conference of mainly young Indonesian activists held at the Australian National University in February this year. It records a fascinating inter-generational meeting being repeated all over the country today. NGOs in Solo (Central Java) and Palu (Central Sulawesi) have brought survivors together into regular discussion groups, where they exchange experiences, discuss books about what others have done, and make their voices heard in the community. The most moving moment of the conference for me was to hear Nurlaela AK Lamasitudju tell how the mayor of Palu apologised to the victims, on his own behalf and that of the city. Compensation is being arranged. This is a first in Indonesia, and the idea is spreading. The organisation Women Speaking Out (Tutur Perempuan) has been holding such meetings in towns in East Kalimantan, Jakarta, Central Java, and Bali since 2005. Discussions are straight from the heart. ‘I want to know where my father is. Where is he? If he did something bad, what was it?’, asked one woman.

Several groups are building audio archives containing hundreds of interviews with survivors. An important aim of the conference was to seek ways of preserving such archives and making them more widely accessible. Others presented their research results on a great variety of topics. One researcher spoke about female prisoners who gave birth and cared for children in detention; another about the bureaucratic procedures by which people were detained for years in Indonesia’s Gulag. Others talked about providing history teachers with more adequate audiovisual materials; about including perpetrators in the oral history archives as well; and about the urgent steps Indonesia’s public prosecutor now needs to take.

The Indonesian-language book Memori-memori terlarang (Forbidden memories) is one of the most intimate records of the inter-generational meeting between young researchers and ageing survivors that have been published so far. The area in and around Kupang, in eastern Indonesia, saw appalling violence in 1965-67, yet public discussion of the subject has always been taboo. The book will come as a bombshell into this conservative majority-Christian provincial society, because it turns the New Order narrative upside down. At its core are the stories of dozens of extraordinary village and small town women, who were imprisoned or whose husbands were murdered. Photographs show the places where torture took place, where bodies were buried, where murderers reigned. These stories are moral barbs aimed at the provincial establishment of Kupang, which seems to have changed little since the 1960s. The civil service is one target; it inflicted precipitous downward mobility on alleged communists who were purged from schools, hospitals and offices around the region. The church is another; in 1965 it ostracised all those associated in any way with the hitherto legal communist party. The petty aristocracy are also guilty. Privileged under the colonial Dutch, they had seized peasants’ lands and then collaborated with soldiers to persecute those who protested in the 1960s. ‘This book does not simply present lessons from the past, but asks us to enter into that past and try to bring about healing,’ writes the Protestant theologian Andreas Yewangoe in the foreword.

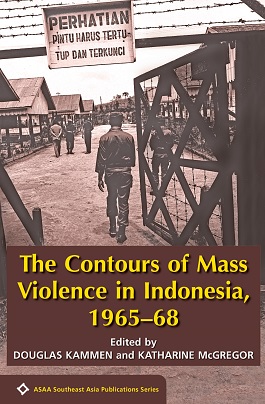

The Contours of Mass Violence brings together historical research by foreign and Indonesian scholars. It is well-edited, and will make great university classroom material. International complicity in the crimes becomes devastatingly clear in a chapter by Bradley Simpson. A series of regional studies by both well-known and younger scholars bring to light a wealth of new material. While centrally ordered, the 1965 killings varied in different regions, reflecting class and ethnic relations there. Whether or not the area had a history of mass violence also seemed to play a role. The violence in East Java, for example, was exacerbated by tensions between liberals and conservatives within the religious organisation Nahdlatul Ulama. Once sure they had official backing, the latter acted out their hatred with such savagery that the military actually had to rein them in.

Two chapters most directly address the question of whether the New Order narrative on the killings might crack. The first is John Roosa’s on the history of that narrative. In the late 1960s it was not easy to explain to the Indonesian public why it was necessary to kill so many ordinary people in order to reset the nation’s geopolitical posture. Those who tried inevitably became tangled in contradictions. The narrative(s) they wrote were not designed to withstand serious scrutiny and open debate. It is difficult to imagine how they can survive in today’s democratic Indonesia.

The second is Katharine McGregor’s evocative closing chapter on mass graves and memorialisation. In some countries, victim organisations have succeeded in reversing a long-accepted national narrative about the past. Argentina’s confrontation with its Dirty War is a good example. ‘New Perspectives on the 1965 Violence in Indonesia’ proves that Indonesia’s victim organisations do not lack courage. But are they about to persuade all of Indonesia to turn down an Argentinian path? Or will Indonesia continue to resemble Guatemala or Russia – two other countries where Oppenheimer’s ‘victorious Nazi’ scenario seems frighteningly real? Several Indonesian victim organisations have attempted to open mass graves, but in every case violent men linked to conservative religious groups and the military stopped them.

One thing is certain: 50 years on, this story is only just beginning.

‘New Perspectives on the 1965 Violence in Indonesia’, proceedings of a conference held at the Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, 11-12 February 2013. [Listen to an SBS radio interview with conference organiser, Sri Lestari Wahyuningroaem; and for queries about the papers presented at the conference she can be contacted directly at sri.wahyuningroem@anu.edu.au.]

Mery Kolimon and Lilya Wetangterah (eds.), Memori-memori terlarang: perempuan korban & penyintas tragedi '65 di Nusa Tenggara Timur. Kupang: Yayasan Bonet Pinggupir, 2012. An English translation is in process as part of the Herb Feith Translation Series, sponsored by the Herb Feith Foundation.

Gerry van Klinken (Klinken@kitlv.nl) is researcher at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies (www.kitlv.nl) and professor at the University of Amsterdam.