Controlling local corruption is one thing; tackling the big guys in Jakarta is quite another

Ari Kuncoro

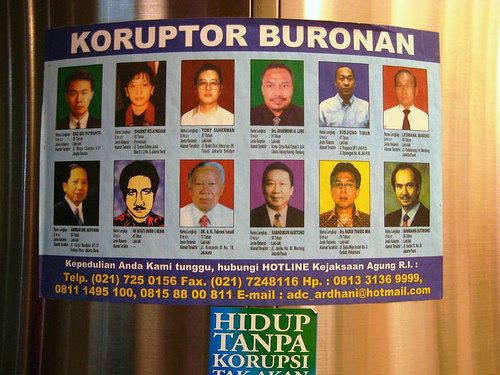

"Wanted for Corruption" poster in Hang Nadim Airport, Batam, Riau Islands, August 2007.Martin Manurung (Flickr) |

The word ‘corruption’ has many meanings, but economists use it to mean ‘the misuse of public office for private gain’. Corruption works against economic efficiency mainly because it is secretive. From the point of view of private companies, corruption is like taxation, since both take money from private business. But corruption is illegal. The need to avoid detection and punishment makes corruption less efficient than taxation. A bribe is a contract that cannot be enforced in court. This creates the opportunity for the bribe-taker to renege – or to demand a higher bribe from the buyer.

Under the Suharto regime, corruption was apparently compatible with high growth. Unlike in most corrupt countries, corruption in Indonesia seemed to inflict little cost on economic development. Do different kinds of corruption perhaps impact differently on efficiency? One explanation, put forward by the economists Shleifer and Vishny in 1993, distinguishes between centralised and decentralised bribery. The latter is worse for economic growth than the former. In Soviet Russia, the communist party centralised the collection of bribes and established mechanisms to stop deviations from the agreed pattern of corruption. A buyer of government goods (permits) received a guarantee that he or she was getting the whole package, and would not face any more requests for bribes from other parts of the bureaucracy.

Similarly, in South Korea bribes are mostly paid in the form of lump-sum contributions by major business leaders to the president’s campaign fund, and this buys them all-round protection. In post-communist Russia, on the other hand, different ministries, agencies and levels of local government all set their own bribe rates independently, in order to maximise their own revenues. This is bad for the economy. The same thing happens in India and some African countries.

In Suharto’s Indonesia, corruption was centralised and predictable, somewhat like that in communist Russia or South Korea. Indonesia and India were about equally corrupt, but Indonesia’s economic performance was better. Corruption was controlled by the first family and the top military leadership, in partnership with ethnic Chinese conglomerates. Although business complained about it, investors could accurately predict the costs associated with corruption and bureaucratic red tape and factor it into the cost of doing business. Many of them involved Suharto’s children in their private businesses in an effort to reduce the uncertainties that might be created through harassment by lower level bureaucrats. The pattern was repeated in the provinces. Businesspeople invited family members of prominent figures such as governors and local military commanders to join their ventures as a form of protection against harassment from more junior bureaucrats.

Decentralisation

Corruption in post-Suharto Indonesia is quite different. Indonesia launched an ambitious regional decentralisation program in 2001. Instead of being centralised, power and authority are now more diffuse. Centralised corruption – one-stop shopping – is also gone, replaced by a more fragmented bribe collection system. Today many players, from central ministry and other government officials, through legislative members at the national and local levels, to local officials, soldiers, and police officers, are demanding bribes. Their failure to coordinate their bribe-taking behaviour will likely result in a higher total level of bribes. The number of bribe-takers has increased to such an extent that it is now more detrimental to economic efficiency than in the Suharto era.

The number of bribe-takers has increased to such an extent that it is now more detrimental to economic efficiency than in the Suharto era

While in other countries decentralisation may have nothing to do with corrupt behaviour, in Indonesia, already burdened with Suharto’s corruption, it only worsens the fragmentation of the bribe collection system. The Indonesian Chamber of Commerce (Kadin) has complained that decentralisation produces new local regulations in the form of taxes, levies and permits, which in turn have driven up corruption at the local government level. The phenomenon is called ‘overgrazing the commons’, because it involves officials from all levels of government and many different agencies preying on the same economic activities. To summarise, although important non-economic factors also play a role, the main reason why corruption is now more damaging to the economy than it was under Suharto is the fragmentation of the bribe collection system, involving the entry of new corrupt agencies into the political system.

Democracy

Democratisation has turned corruption into a potent political issue. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono made tackling corruption his central campaign promise and quickly established the Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK). For the purpose of ‘testing the waters’, and also so it could avoid targeting national figures, the first phase of the post-New Order anti-corruption drive has been conducted at the level of provinces and districts. Many provincial and district officials have been prosecuted. These cases often touch the top officials in the regions. From the start, anti-corruption efforts have produced prosecutions but little institutional reform. The judicial system and the civil service are in need of serious reform. Some experiments have been made, such as raising salaries of judges and of some civil servants, but the results are not yet satisfactory. The scandalous acquittal by the South Jakarta court of former Bank Mandiri director E. C. W. Neloe in his first corruption case is just one example.

From the start, anti-corruption efforts have produced prosecutions but little institutional reform

In 2006, a bribery scandal involving the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court Bagir Manan and wealthy entrepreneur Probosutedjo (half-brother of former president Suharto) offered a hint that corruption had reached the highest level of the judicial system. Meanwhile, an experiment to improve civil service remuneration has been limited to the Ministry of Finance, although there are some encouraging signs elsewhere, particularly in the Taxation Directorate and the National Custom Service.

Anti-corruption prosecutions are having some effect, particularly at the district level. The increasingly dense web of regulation supporting the decentralisation process is also helping reduce regional corruption. Local government agents are increasingly assigned tasks that are specific to their jurisdiction, such as education, minimum wages, business licensing and so on. They are therefore subject to direct local accountability mechanisms through local legislatures, local media and local voters. Decentralisation also places a greater part of the development burden on the shoulders of local government officials. Local governments realise that, if they want to attract investors to their region, they need to create a clean, predictable bureaucratic environment. Competition between regions for the business dollar may in the end make local corrupt behaviour less sustainable.

Parties are learning that they will gain votes only if they can prove they are serious about being clean

Another encouraging development at the local level is that the issue of corruption is a powerful vote-getter. In recent provincial governor elections in West Java and North Sumatra, evidently corrupt and inept incumbents were soundly defeated despite enjoying the support of big political parties. Parties and candidates for executive office are learning that they will gain votes from uncommitted, apolitical voters only if they can prove they are serious about being clean.

Local results may provide optimism for the national level. Indeed some cases before the courts today do involve national leaders and politicians. Former Minister of Religion Said Agil Husein al-Munawar was in 2006 jailed for seven years for corruptly using Mecca pilgrimage money; former Minister of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries Rokhmin Dahuri in 2007 also received seven years for running an off-budget slush fund. Several former or current directors of state enterprises are now also in court or jail, among them former Bank Mandiri president director Neloe (for the second time).

But pursuing national-level corruption at the same speed as has happened in the regions may prove a formidable challenge. An example is the case brought to light in April 2008 in which the central Bank of Indonesia paid large bribes to national parliamentarians debating a new finance bill. While the deputy governor of the bank was detained (and the governor of the bank had been arrested earlier over another scandal), catching the big fish in parliament proved to be more difficult. KPK’s probing so close to the core of the political system appeared to make the president himself uncomfortable. On one occasion President Yudhoyono publicly disapproved of the KPK’s method of ‘sting’ operations.

One urgent issue in the new democratic Indonesia is political party funding. Much of the parties’ money is thought to come from corrupt government officials. The Rp100 billion (US$ 10 million) transferred from the central bank to several members of the national parliament, referred to above, is just one example. Corrupt money also oils other parts of the political machinery. There are intermediaries or brokers (calo) who use their money to influence members of parliament when they make important decisions, such as filling an important public office, making a budget allocation or fast-tracking a draft of a law. The bigger the bribe, the higher the chance of success.

One example was the case of lawmaker Al Amin Nasution, who was arrested in April 2008 for receiving a bribe from Riau Islands provincial officials in return for persuading the Ministry of Forestry to change the status of some land sites in Bintan Island. Many Indonesians believe the arrests so far have only exposed the tip of an iceberg.

As long as corruption in core national institutions of the state is addressed only half-heartedly, the prospects for substantial improvement remain dim. A respected enforcement agency like KPK must continue to function without intervention from politicians. In this new, more democratic environment, as demonstrated at the local level, political competion has the potential to reduce corruption. But this can only be effective if the judicial system and the civil service are cleaned up. In order to succeed nationally, the anti-corruption drive must be accompanied by sweeping reforms in the judicial system and the civil service. ii

Ari Kuncoro (arik@cbn.net.id ) lectures in economics at the University of Indonesia He obtained his PhD in 1994 from Brown University, USA, and has written widely on the politics of rent-seeking in Indonesia. This article is from a presentation at the Amsterdam conference 'Ten Years After', 22-23 May 2008 (KITLV, University of Amsterdam, Inside Indonesia).